16 - Subsequences and Cauchy sequences

Where we left off last time

Where did we leave off last time and where were we going?

-

Recap: Last time we talked about sequences and what it meant to be a sequence in a metric space. And we talked about how to prove that a sequence converges to a particular point. We'll talk a bit more about sequences today and sequences (their relation in particular) and what it means to be a Cauchy sequence.

-

Warm up: Last time we talked about what it means for a sequence to converge to a point; in particular, we said converges to means the following:

We wrote or to communicate this. So so long as no matter what you give me there is some point in the sequence (namely ) beyond which all the points are within of :

Let's now consider what happens in or .

-

More warm up: Consider the sequences such that and .

-

Theorem 1: Given such that and , we claim that

The important idea of the sequence convergence definition is to find an . To show convergence, you must find an for every . How does that play out in the proof of this theorem? What are we trying to do? With , we were trying to bound the distance between and . Here we will be trying to bound the distance between and . So we have to show that is close to . What do we know? What are we assuming? We are assuming that and ; that is, is close to and is close to . We know these distances are small, and we want to show that the sum of the distances is small. Thus, essentially, we want to show that is small. In fact, we are trying to show that for some given . And we want to know at what point in the sequence is the quantity small. Well, we know and are both small. So can we try to bound in terms of two things which we already know to be small? By the triangle inequality, we know that

and the idea is to somehow use this bound. Since will be small eventually, it must be the case that will also be small eventually. Now, of course, the two "eventually" locations at which and become small may be different.

For instance, if we want to be really small, this may not happen until . And if we want to be really small, then this may not happen until . So if we want to be really small, then we need to ensure that both and become really small. Let's flesh this out more precisely.

Given , there exist positive integers such that if then and if then . Let . Then, for , we have

as desired. Thus, .

-

Proof technique: The proof for the theorem above points out a key proof technique. One sequence converges, maybe not as fast as the other, but our job is to find a point in the sequence beyond which we can bound our sum, as motivated before the precise proof above.

-

Theorem 2: Suppose is a scalar and that . Then

and

Let's just do one of these, the first one. What idea should help us show that . What bound are we interested in? What should we bound? Let's bound , and we hope that gets small eventually. What do we know is small eventually? We know that ; thus, is small eventually. So how can we connect the value to ? We have

Let's actually prove this now.

Given , there exists such that implies . Then for this (emphasis just to illustrate that we found our ), implies that

as desired. So .

For the other proof, given , there exists such that implies . Then implies that

as desired.

-

Theorem 3: Given and , then . What should we be trying to bound here? We should be trying to bound . We note that

where this idea may seem quite random at first. It's rather natural to first look at the product , but we get cross terms and the signs are all wrong. We add the other terms to balance things out. But the equation above is quite good because we can ultimately look at the core part of the identity as follows:

For the above, we note that the and outside of the parentheses are really scalars, and so we may possibly apply a theorem we just proved here. There are many good things about our seemingly "out of the hat" way of rewriting . Of course, the trick now is to figure out which works. That's what's more difficult here. Let's prove this now.

Given , let . Then there exists such that implies that . Similarly, implies that . Let . Then . We have a slight problem with the term. The issue involves both and . What could we do? Well, if , then , and I can get rid of one of the squared terms because . We would have the following:

How can we make sure the modifications\slash restrictions to our choice of actually work? We can let to ensure we obtain the desired conclusion above.

-

Strategy for showing sequences converge: Your goal is to find an . The idea you start with is to bound the thing (i.e., the sequence and its limit) you want to show converges, and you want to do so in terms of things you know are small.

Subsequences

What are subsequences and why are they important?

-

Motivating idea: Suppose you have a sequence and you look at a set of indices in an increasing sequence, where this needs to be infinite. Then is a subsequence.

Consider, for example, the sequence

What is a subsequence exactly? Well, a subsequence is basically picking out a sequence that's a subset of the original sequence. So we could look at

to begin the subsequence

It looks like the original sequence converges to 1, but does the subsequence converge? Maybe it converges to 1 also. Are there subsequences that don't converge? Does every subsequence of our original sequence have to converge? Does it have to converge to 1?

More specifically, if , then must every subsequence converge to ? Yes. There's a fairly easy way to see this which is based on something we showed last time, namely that every neighborhood of a convergent sequence contains all but finitely many points. That is, every neighborhood of contains all but finitely many points of . So if that's true and we have that , then it's easy to show that the subsequence converges to the same . In fact, you can tell how far in the sequence you need to go. For example, if you need to go out to the 100th term to get the sequence to be within of the limit, then how far do you need to go to have the subsequence be within ? Well, 100 would certainly work! You actually may only need to go less far. So subsequences of convergent sequences also converge and to the same limit. What about sequences that don't converge? Could they have convergent subsequences? Sure.

-

Convergent subsequences of divergent sequences: Consider the sequence

which certainly does not converge. But it does have a subsequence that converges. Certainly the sequence would work, but that's not the only one! The subsequence

would also work. There are many other convergent subsequences, in fact. The subsequence could also work, etc. We have a name for such limits. They are called subsequential limits.

-

Existence of convergent subsequence for divergent sequence: Must every sequence contain a convergent subsequence? No. How about the natural numbers? We would have , and that certainly does not have a convergent subsequence. If there were a subsequence that converged to some number here, then you could show that beyond some point you are bigger than and you'd never be close to . Can't have a convergent subsequence. Must a bounded sequence have a convergent subsequence? In general metric spaces, this is not true. Let's consider an example to see why this is true.

Consider the metric space with the usual metric. Then the sequence

does not converge, and it does not have a convergent subsequence either. In at least. Of course, if you are working in , then the original sequence does converge, namely to , and every subsequence would as well. So, in general metric spaces, it is not necessarily true that a bounded sequence has a convergent subsequence, but it seems as though if we are in or then we may have this fact. What about in general compact metric spaces?

-

Convergence of subsequences in compact metric spaces: It seems as though if we are dealing with compact metric spaces, then any sequence should have a convergent subsequence. It may help to first introduce a definition not in [17]:

Sequentially compact metric space: A metric space is said to be subsequentially compact if every sequence has a convergent subsequence that converges to some point of .

And the question was really whether or not it is true that a compact set is also sequentially compact? Does compactness imply sequential compactness? What does sequentially compact really mean? It means a space is "small enough" that every sequence, even if the sequence does not converge, you can find some subsequence that converges. Compactness basically implies sequential compactness.

-

Theorem (compactness and sequential compactness): If is compact, then is sequentially compact. This is stated in [17] as follows: "If is a sequence in a compact metric space , then some subsequence of converges to a point of ." So, in a compact space , every sequence has a subsequenece that converges to a point of .

Without being explicit, sometimes there can be confusion. For instance, the set

looks like it converges, but this is kind of meaningless without saying what space we are in. The sequence above converges to , but . What we are saying when we have sequential compactness is that any sequence has a subsequence that converges to a point in the metric space under consideration, where it is clear from the above set that is not sequentially compact. A fact worth noting but which we will not prove here is that sequential compactness is equivalent to compactness.

-

Corollary of theorem about compactness implying sequential compactness: An immediate corollary of the theorem, "If is compact, then is sequentially compact." is that every bounded sequence in contains a convergent subsequence. Well, is not compact so how can we say this is an immediate corollary? Since we have a bounded sequence, it lives in a compact subset of , and therefore it lives in a compact metric space, so it contains a convergent subsequence converging to a point of that set which is in . This corollary has a special name called the Bolzano-Weierstrass theorem. Let's now prove the theorem of which this result was the corollary.

-

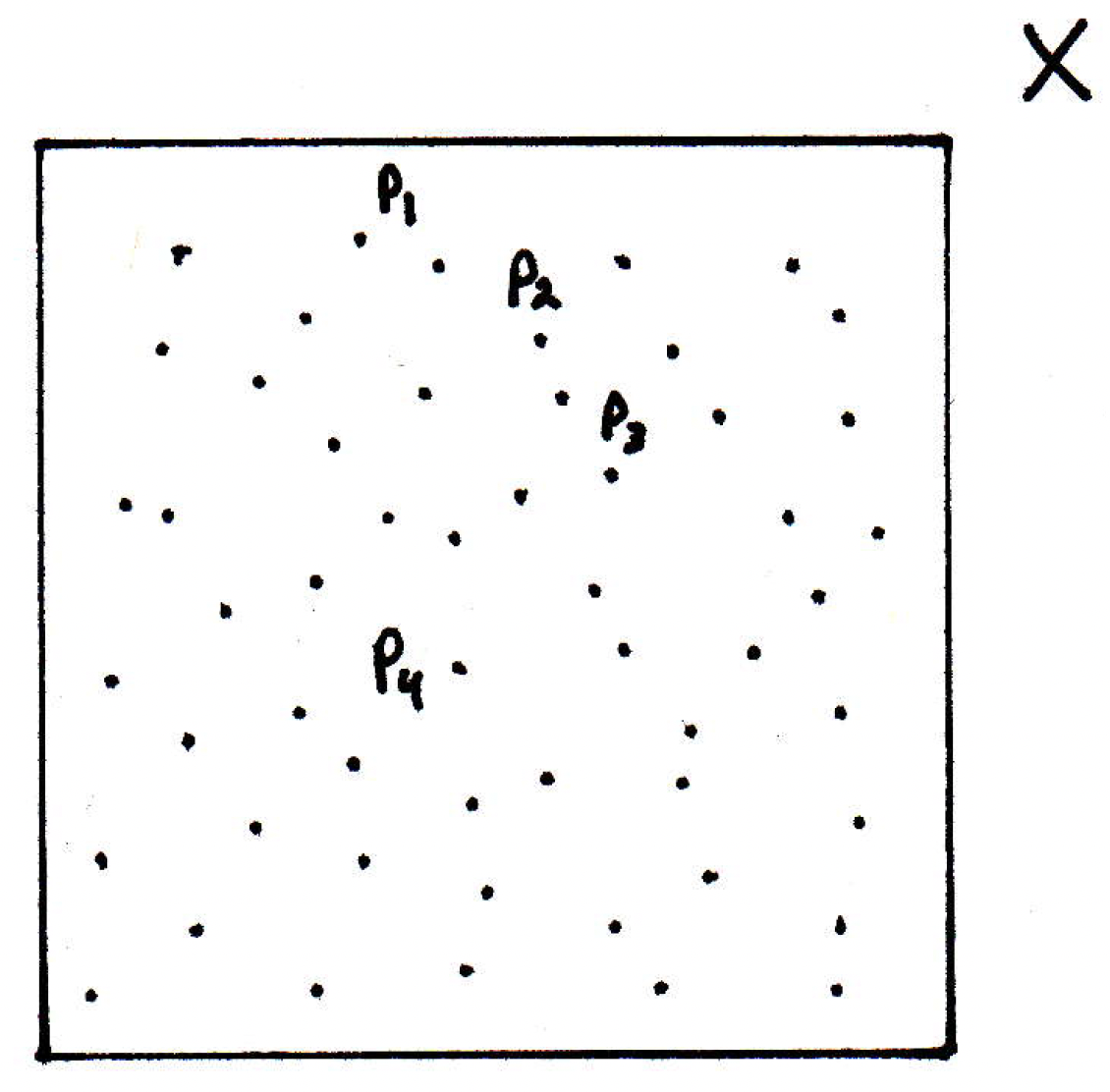

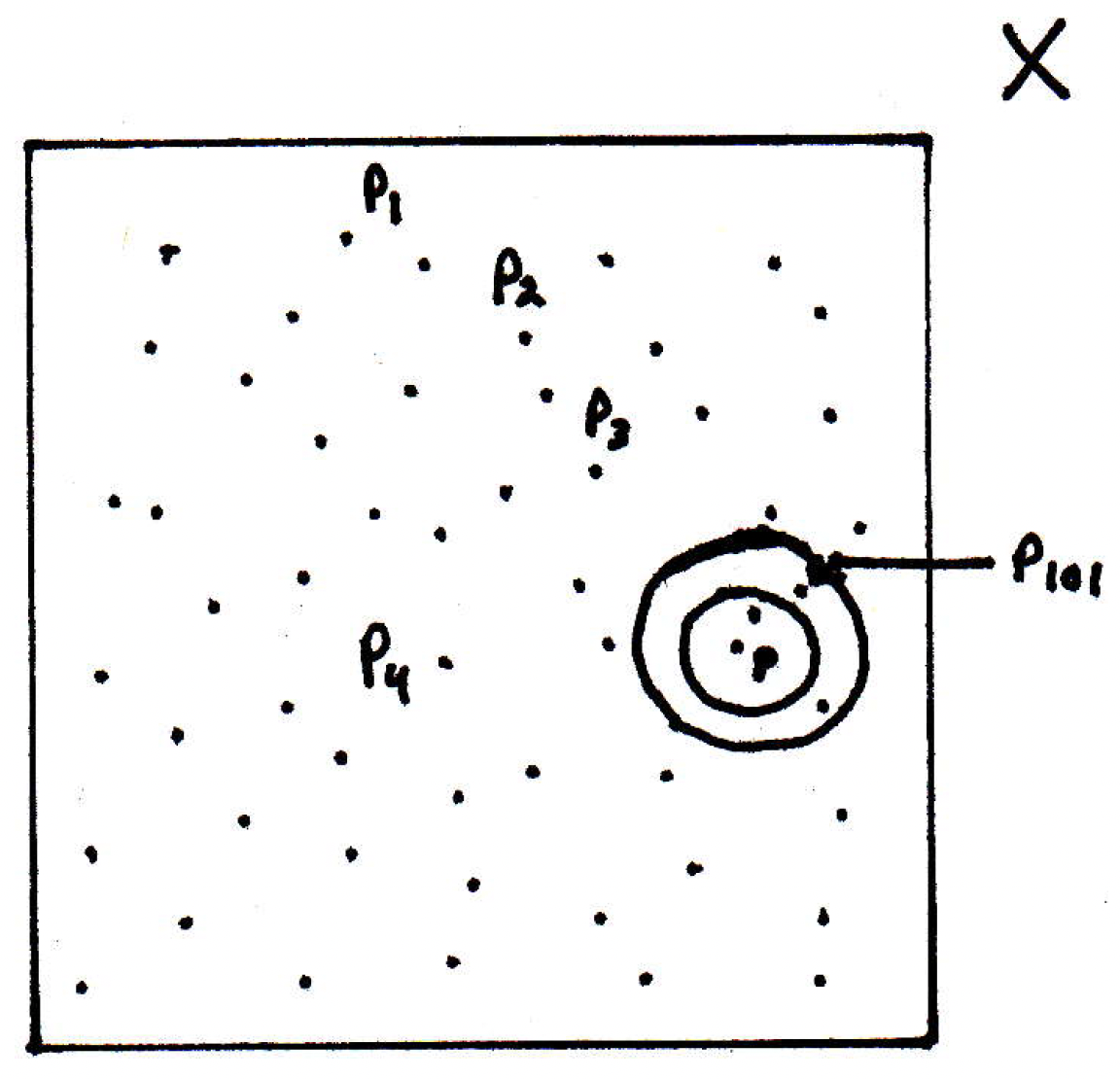

Proof that compactness implies sequential compactness: Why is it that compactness gives us enough to show sequential compactness? Compactness actually gives us many nice things, but what's true here? We have some sequence in a compact metric space that's sort of hopping around perhaps:

There are a couple of cases to consider here. We could consider the case where we let (that is, all the values that are actually hit). If is finite, then can we show that our sequence has a convergent subsequence? Yes, because if we only hit finitely many things and there are infinitely many points of the sequence, then one of those points must be hit infinitely many times. So if is finite, then some is achieved infinitely many times. So you just use that subsequence. This is a version of the pigeonhole principle, namely that if you drop infinitely many pigeons into finitely many holes then some hole must have infinitely many pigeons.

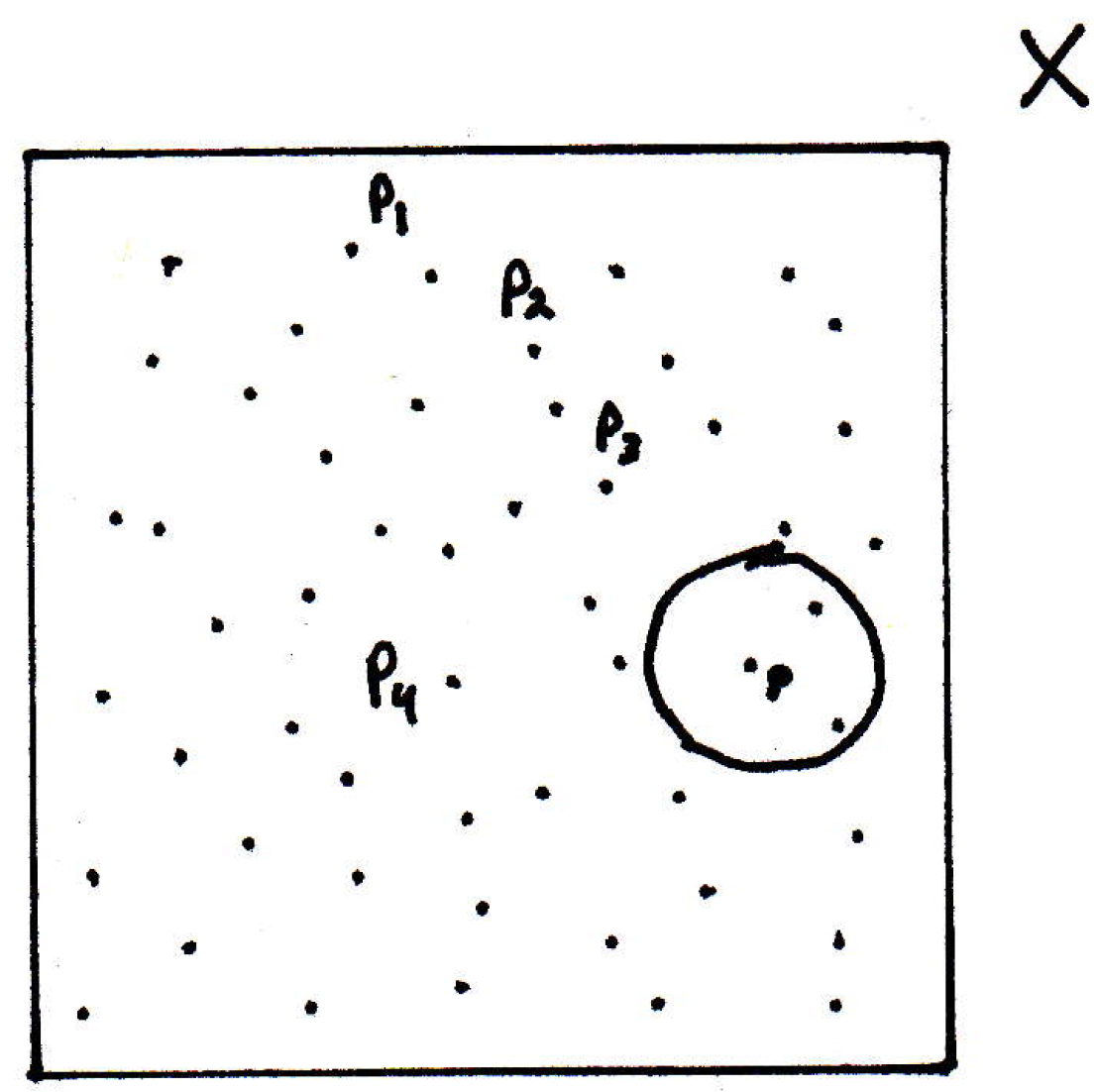

What if is infinite? We'd have an infinite subset of a compact set, and recall that if you have an infinite subset of a compact set, then that set must have a limit point. So in our picture above, what this means is that there must be some point that is accumulated on. There are probably many, but there's at least one limit point. So, if is infinite, then by Theorem 2.37 in [17] (which we proved here in these notes as well), since is compact, has a limit point. Let's call it . Now, the claim is that must be a subsequential limit. Of what subsequence though? We can start labeling some of the points as follows:

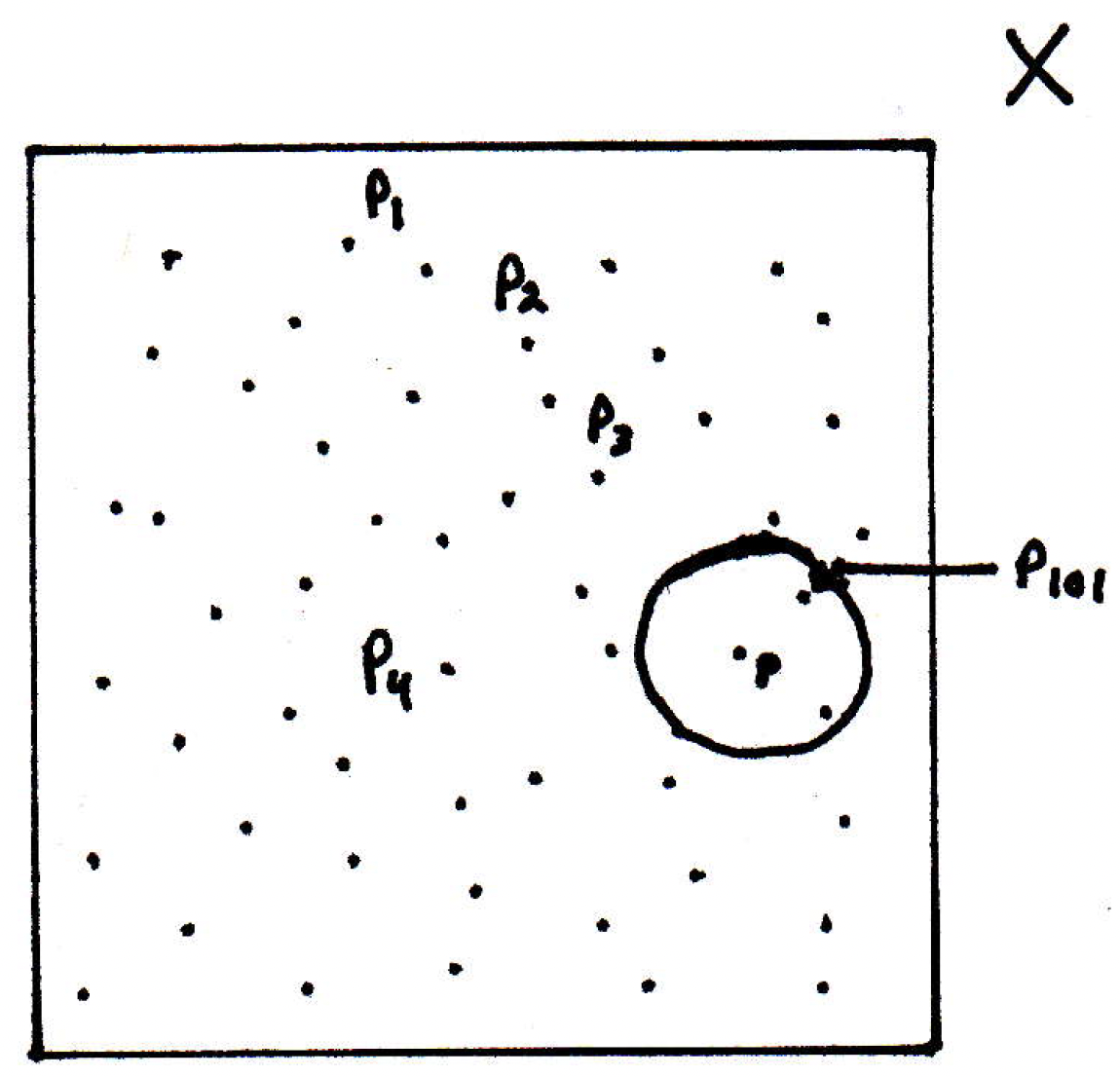

Maybe we label and ask ourselves what subsequence will converge to if it is a limit point:

As noted above, we can take a neighborhood of , say . Eventually, one of the points would live inside of this neighborhood (make the neighborhood as large as you like at first), let's say :

But how could we construct a subsequence that gets closer? We could consider another neighborhood of , say , where there have to be points inside:

In fact, there doesn't just have to be points inside but infinitely many points inside. There must be a point beyond in the sequence that lives in this neighborhood since there are infinitely many points in it. We can use this idea to construct a subsequence.

Alternatively, there exists a sequence in converging to , which we've already shown, but maybe it looks something like this: , , , , , , , \ldots . When we have found this sequence, it's not technically a subsequence because its indices do not increase, but there has to be a subsequence where the indices do increase. Why? Well, there are infinitely many terms beyond so there has to be one that's bigger, namely, . Then you could pick the next bigger one. And when you've picked those ones out, you have a subsequence.

The fact that every sequence in a compact metric space has a convergent subsequence will be appealed to often.

Cauchy sequences

What are Cauchy sequences and why are they important?

-

Motivation: The whole point of studying Cauchy sequences is to try to get a handle on the following question: How can you tell whether or not converges if you do not already know its limit? In other words, in many of our definitions, they require you to know what the limit is of a sequence in order for us to determine whether or not it converges. So you might have a sequence you have no idea whether or not it converges (i.e., whether or not it has a limit) and what that point of convergence or limit could be. Our idea is to define a kind of sequence that gives us a criterion for perhaps being able to answer this question.

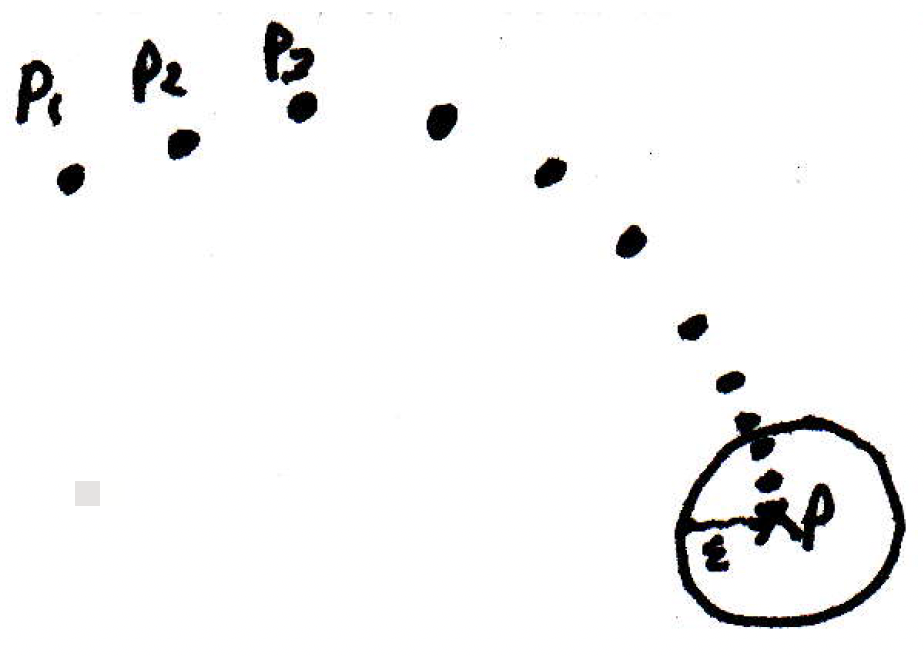

More precisely, maybe we have a bunch of points:

We cannot tell whether or not these points are converging to anything. But if they converge to something we don't know, then the points must be getting close to each other. So if they do converge, then the must be getting close to each other. That's the key idea.

-

Cauchy sequence (definition): The sequence is Cauchy if the following is true:

What's the relationship between this definition and what it means for a sequence to be convergent? Are they the same? What do you think at least is true? If a sequence converges, then it must be Cauchy. Let's prove that.

-

If a sequence converges, then it is Cauchy (proof idea): All we have to do is try to show that points get close to each other, and we know they get close to so how will we show that they get close to each other? What are we going to try to bound the distance between? The distance from to or simply , where we will resist the urge to write because we are now dealing in an arbitrary metric space and not just . What do we know is small? We know the is small and that is small. Maybe we can relate those distances using the triangle inequality:

This is the key idea.

-

If a sequence converges, then it is Cauchy (proof): Given , there exists such that implies that . So for this , implies that

So we know that convergent sequences are Cauchy sequences. What about the reverse direction? Are Cauchy sequences convergent?

-

Are Cauchy sequences convergent?: Consider again the sequence

This sequence in is Cauchy but not convergent. It would be wise to try to pin down conditions for when it is true that Cauchy sequences are convergent. When will this be the case?

-

Complete metric space (definition): A metric space is said to be complete if every Cauchy sequence converges to a point of . So this is a desirable property; it's the property that we want. In a complete metric space, Cauchy means convergent. So it is then natural to wonder what spaces are, in fact, complete. Which metric spaces are complete? We know is not complete. What about ? Is complete?