17 - Complete spaces

Where we left off last time

Where did we leave off last time and where were we going? Something about complete spaces.

-

Cauchy sequences: Last time we made a curious definition, that of a Cauchy sequence, which is a sequence where all the points of a sequence get close to each other, and we wanted to see what some of the consequences of being Cauchy were. We saw that if a sequence converged, then it was Cauchy. In the other direction, we inquired as to whether or not all Cauchy sequences were convergent in every metric space, and we saw the answer was no. This motivated the definition of a ``complete space'' where all Cauchy sequences converge. Thus, in a complete space, being convergent and being Cauchy are the same thing. That is why complete spaces are of interest. But then the big question was which spaces are complete.

-

Spaces that are complete: Last time we saw that was not complete. We conjectured that maybe is. On the way to seeing whether or not this conjecture is true, let's try to establish another conjecture, that about compact spaces being complete.

-

Compact metric spaces are complete: What's an example of a compact metric space? How about the interval ? We know is not compact because it's unbounded. What's another example of a compact metric space? How about a set that is finite? Is it true that in a finite metric space, one with only 5 points in it, you have a sequence that, if it is Cauchy, then it converges? We have 5 possibilities, and I have to pick an infinite string of things, and they all get close to each other eventually, then what must be true? This sequence, which may hop around initially, must do what? It must settle down on one and stay because all the points are getting close to each other. As soon as gets smaller than the minimum distance between 2 points, then all the points have to be at the same point of the space. That's kind of a trivial theorem when the space is finite.

Compact spaces are a little more interesting concerning convergence, but they are not too far off the idea presented above for finite sets. And remember that compactness is the next best thing to being finite. The proof below will use the insight we established last time, namely that compactness implies sequential compactness. So we are going to use that fact.

To show a space is complete, what we want to do is take a sequence, say , and let it be Cauchy in . What is our goal? Our goal is to show converges. To do that, of course, we need to figure out what point it converges to. That would be nice to specify here. Now, since is compact, it is sequentially compact, meaning every sequence has a convergent subsequence. How are we going to use that fact here to show that converges? Well, there exists a subsequence, converging to a point of . Let's call this point of convergence .

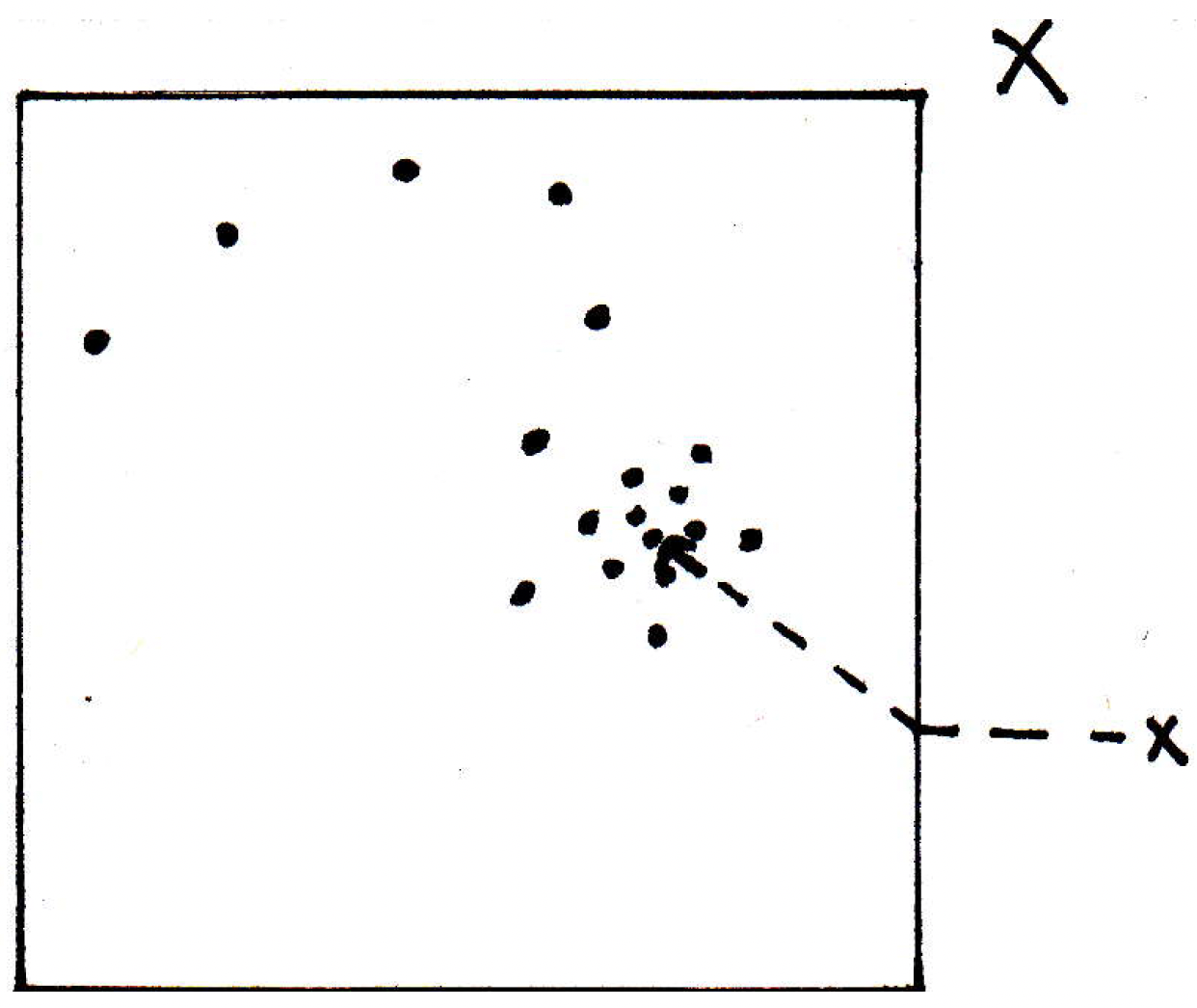

Let's draw ourselves a picture of a sequence in and a point of interest:

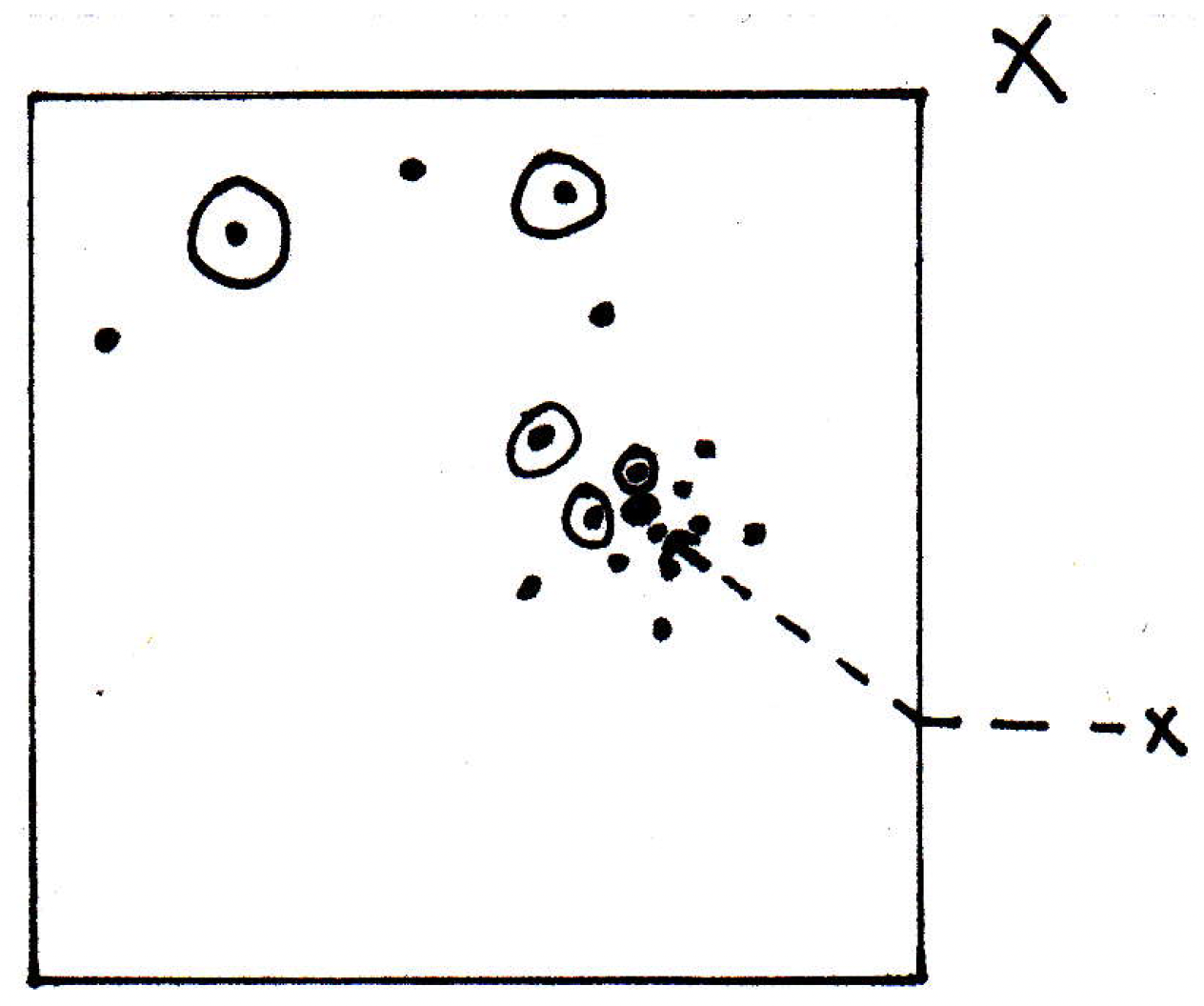

In particular, we've identified a subsequence (the circled points) which appears to be converging to :

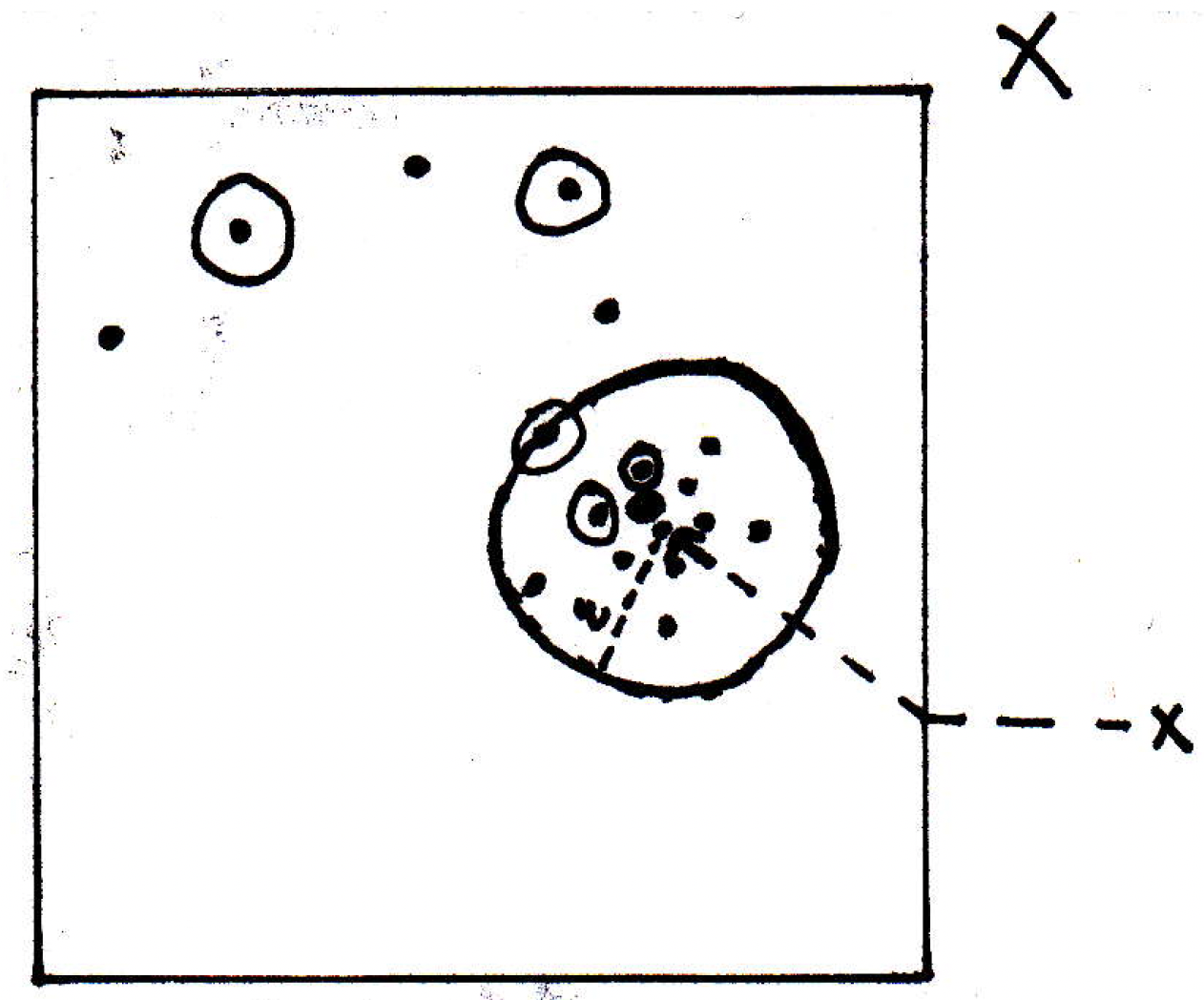

Where do we go from here? We want to show that the entire sequence converges to the point . How are we going to show that all of the other points also get close to if our subsequence gets close to ? Consider one point that is not circled. Past some point of the sequence, non-circled points are all close to circled points. And circled points are close to . So what we want to try to do then is show that non-circled points are also close to . For any , we want to show that all the points are eventually within (in the picture we've zoomed in):

So past what point of the sequence would we like to take a look? Well, past a point that will get the circled points within how far of ? How about ? So maybe past some all the circled points are within of . Past some point there's a big for which that is true:

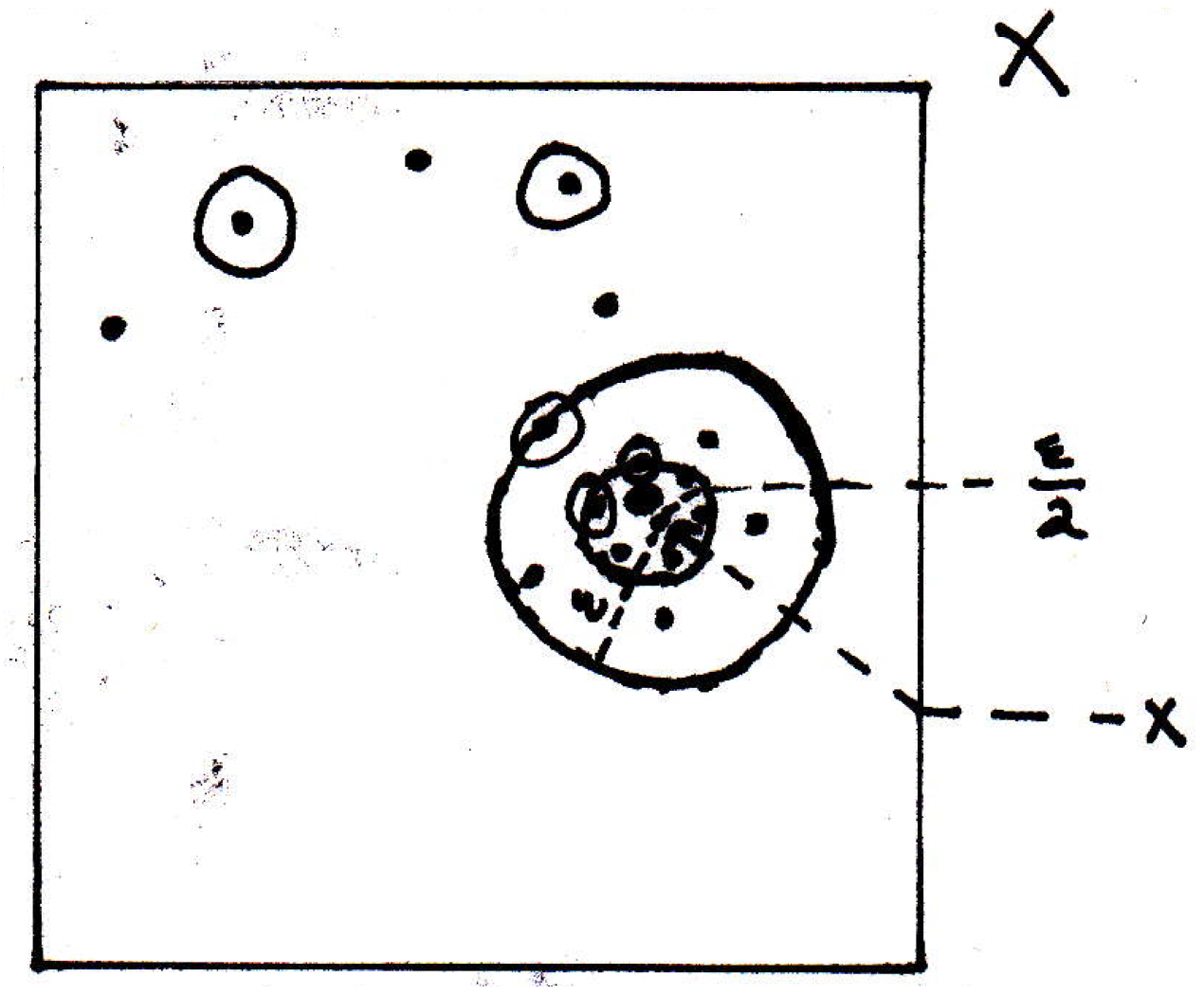

How far would we like to look for the Cauchy part? How about when they are within of as well? And that might happen for a different index . Then take the maximum of the indices beyond which both of these things are true. That's the basic idea. Let's make this precise.

Fix . Since is Cauchy, there exists such that if , then . Since is compact, it is sequentially compact, which means we have a subsequence that converges to . That is, there exists such that implies . Let . If , then for any (fix one). So we have

Thus, given , we found an that shows . So we've used the Cauchy definition here in a very essential way. So what does this mean? It means is complete. And this is for any sequence since was arbitrary.

An exceedingly quick corollary is that is a complete metric space. Not only that, but if you want to look at a compact set in a larger space, isn't the -cell complete? Yes, the ones in . Lots of things now we know are complete. Is complete? It's not compact, we know that. Is Euclidean space complete? Yes! Why? We've just shown that compact spaces are complete. Even though is not compact, can we show that it is complete? Can we show that every Cauchy sequence converges? Yes. Before doing this, one thing to note is that another example of complete spaces is if you take a closed subset of a compact set, then it must be complete because they are compact. In particular, Cantor sets are complete. As another corollary, is complete. This is basically easy to justify because Cauchy sequences are bounded and they'll live in a bounded subset of . Let's write out the proof idea.

-

is complete: If is Cauchy, then it is bounded. (To show Cauchy sequences are bounded, recall the mental picture: The points are getting close to each other. So you give me an , and past some point in the sequence all the points are within of each other; thus, there are only finitely many points are not. So basically take one of the points within , and look at the maximum distance from it to all the points not within and add as well. More concretely, let . Then there exists such that for all we have . So let . So the sequence is bounded by a ball of radius around or simply by .)

So if a sequence is Cauchy, then it is bounded. If it is bounded, then it is in a ball. If it's in a ball, then you could just put it in a closed ball or a closed -cell. So some -cell in , so is complete and converges because -cells are complete.

What have we just done? We have shown that if we take a Cauchy sequence in , then it necessarily converges. That is, is complete. What does this mean? Well, in the space we care most about, namely , to be Cauchy is the same as being convergent. So we don't need to know what the limit is of a sequence to show that a sequence actually has a limit.

-

Example 1: Does the sequence

converge? The first term is 1. The second term is 1.5. And so on. If you just write out the first few terms, then it's unclear whether or not it converges. In fact, grows very slowly. Does it converge? How could we tell? We could ask whether or not it is Cauchy. If it is Cauchy, then we know it converges. If we show it is not Cauchy, then it diverges.

Consider the difference between the first reciprocals and the first reciprocals (where let's just assume ):

Let (there's nothing you can do to stop me from doing that), then we see that

and this is true for every . Does this sequence have any hope of being Cauchy? No, it cannot be Cauchy because as soon as you let , then you will never find a point in the sequence beyond which all of the terms are closer than from each other because we've just shown that pairs of terms infinitely far out, as far as you would like to go, have a distance greater than from each other. So this sequence is not Cauchy and therefore diverges.

-

Example 2: Suppose , , and . Does this sequence converge? Well, we have no idea what its limit is, but if we can show it is Cauchy, then we will know whether or not it has a limit. It will not tell us what that limit is, but it will tell us whether or not it exists. This sequence is Cauchy and therefore converges in , but this would not actually be the case in because we wouldn't know if the limit were rational. Where do such sequences arise? Lots of places such as recursive methods for finding roots. This is Newton's method. You can show it converges theoretically without finding its limit.

Incomplete spaces

What happens if we look at spaces that are not complete?

-

Embedding an incomplete space in a complete space: If is not complete, can it be embedded in a space that is complete? It's helpful to think about a universe that consists only of , and maybe we could say a sequence converges not in but to some point in a larger space, which we have not yet defined. So can be embedded in , it turns out, and we can see why the more general question of embedding an incomplete space in a complete space might be of interest.

-

Theorem about embedding metric spaces: Every metric space has a completion . What do we mean by completion here? What we mean is there is a way to define a big space that has, as a subset, a smaller space , such that the metric on the big space, when restricted to the smaller space, gives the same metric as the small space. Let's sketch out the idea here. Before doing so, it's instructive to think about the fact that there may be many completions. Thus, in what sense, if any, is the completion we are about to construct unique, as it is defined? Because we could, for instance, embed in . So this theorem says there is a completion, but the proof actually shows you exactly what completion it is, and the construction is actually unique, as it is defined, but there could in theory be several completions that are not isomorphic, but the one the proof suggests is unique.

-

Idea for metric space embedding theorem: In what follows, where is written, think for ease of thought, but could be any metric space. (See [17], exercise 24, for the full exercise.) How are we going to get at those things that are not already in the space? We've done something like this before. We can use Cauchy sequences! If my space has some gaps in it, then well we cannot really talk about the gaps because we don't have a way of defining them (recall the problem with nailing down what actually was). Maybe we can get at those gaps using things that are already in the space, namely the Cauchy sequences that are in the space!

Given , let , but there is a slight problem with this definition of . If we left the definition of as it currently stands, then there are way too many things in this space. It's huge. So imagine the rationals. There are lots of Cauchy sequences that converge to 0. So I don't want to say they are all different. So I am going to look at the set of all Cauchy sequences under an equivalence relation!

Thus, given , let

and of course we now have to say what the equivalence relation actually is. We will say are equivalent if . (Note how we avoided saying and are equivalent if they have the same limit because some Cauchy sequences do not converge or have a limit in some metric spaces. So we will say they are equivalent if their difference gets small, and we communicate that idea by writing .) What's beautiful here is that you can define a metric on this. For , where we note that and are points in our metric space while each one is a sequence in the other metric space , let's define a distance between them. Let , where and , and note that these are simply equivalence class representatives of and , respectively. Of course, we have to show that is well-defined (i.e., if you pick two different representatives then you will get the same distance), and that is exercise 24(b) in [17]. Then is complete with isometrically embedded in , where isometrically embedded means there is a bijection with a subset of that preserves distances. What should that bijection be? Which sequence in should I correspond with a point . How about , , , ... . This is what's called the completion of . So if you do the completion of with the way we have defined , then you get and nothing else. So it is actually a unique construction here that we have for the completion. So this is another way of constructing from .

Bounded sequences

What is the deal with bounded sequences and why are they important?

-

Monotonically increasing (definition): A sequence of real numbers is said to be monotonically increasing if .

-

Monotonically decreasing (definition): A sequence of real numbers is said to be monotonically decreasing if .

-

Theorem about monotonic bounded sequences: Suppose is monotonic. Then converges if and only if it is bounded.

Why do these sequences converge? They are increasing or decreasing to some bound . What do they converge to, if anything? Their supremum (when increasing) or infimum (when decreasing). Let's prove this.

Given , let . Why does converge to as a sequence? To show convergence, for every , we have to find an beyond which everything is within .

Given , there exists such that . But then for all we have , so this works for . This is the idea.

-

Statement about regular boundedness: Some sequences diverge not because they bounce around but because they keep going in one direction.

Let be a sequence of real numbers with the following property: For every real there is an integer such that implies . We then write

Similarly, if for every real there is an integer such that implies , we write

We should note that we now use the symbol for certain types of divergent sequences, as well as for convergent sequences, but that the definitions of convergence of limit are in no way changed.

-

Note about subsequential limits: Given , let , where we may allow and to be subsequential limits here. There's no harm in doing that. So now we could ask something about this set . As a set, may have a supremum and infimum. Let

where note that and will always exist because we are working in the extended reals. We may have , but that is not a cancer. It is worth noting, however, that and are often called the upper and lower limits of , and we use the following notation to communicate this:

-

Note about limit superior and limit inferior: We can think of the limit superior in the following way: The limit superior is the limit of a certain set of suprema, and really what you're doing is you're looking at all the terms past a point (so below look at all the bigger than , take their supremum, and then take the limit as goes to infinity):

The net effect of this is it chops off all the initial behavior of the sequence, and you're only looking at the long-term behavior of the sequence, and this concept arises when we talk about ratio tests. This is similar for the limit inferior:

You can prove that the formulations above are equivalent to the definitions for and .

-

Example 1: If then . If the whole sequence converges, then we must have because we're just chopping off the initial behavior looking for the lower subsequential limit and the upper subsequential limit, and all subsequential limits have to be if it converges.

-

Example 2: Let

What are and ? It looks like and . If we were to say a number is bigger than the , then what is another way of saying that? Does it mean that all the terms are less than if ? No, but it must mean what? Not all the terms are less than , but can we say that eventually all of the terms are less than ? Yes, eventually that has to be true if . (This is stated precisely as Theorem 3.17(b) in [17].)