11 - Compact sets

Where we left off last time

What have we been doing thus far in real analysis and what is some of the motivation for compact sets?

-

The infinite: In dealing with our analysis of the real numbers, we are, in some sense, wrestling with the infinite. In what way are we wrestling with the infinite? What are some examples? The real numbers form an infinite set. Yes, and that was a little problematic at first because we had first of all infinitely many integers and when dealing with the construction of we had to deal with infinitely many pairs of numbers or numerators and denominators for fractions. And then we had this idea that there gaps still. And we wanted to fill them in somehow. That's really wrestling with the infinite. What are some other ways in which we wrestled with the infinite? Well, we had this idea that somehow there are bigger sets, that somehow the real numbers are larger than the rationals. Countable and uncountable infinite sets. Later on we are going to start talking about functions. Functions, in particular, we are often dealing with continuous functions, but what does it mean for a function to be continuous? That's really wrestling with the infinite because if we had a continuous function on a finite set then that would be rather boring.

-

Finite sets are nice: Why are finite sets nice? Well, they are small sets (i.e., bounded). There are only finitely many things. No better way to say it. Of course, the associated idea here is boundedness. What's another reason finite sets are nice? Well, they're closed sets in a rather trivial way since closed sets are those sets that contain all of their limit points. And finite sets have no limit points so they clearly contain all of their limit points. This will become apparent why we care about this soon. In the metric space that's the real numbers, finite sets actually contain their supremum and infimum. And if they contain their supremum\slash infimum, then we can rightfully talk about a maximum or minimum. That is, in , finite sets contain their and their . (Thus, we can think about maximums and minimums.) You give me a set of finite numbers then I can say there's a maximum and a minimum — what I mean is there's a supremum\slash infimum and it's in the set. Finally, another reason we like finite sets is that when doing things with finite sets, the process ends! It terminates. Okay but we're wrestling with the infinite in this course.

-

Compactness: The idea of compactness is really about finiteness. In particular, if you have a set that is compact, then it is the next best thing to being finite. So compact sets are "the next best thing to being finite." That's a good way of thinking about compact sets. Now, when I make this definition of what it means for a set to be compact, it will not be apparent at first why any of these things are true about compact sets, but they are. Each of the things mentioned above for finite sets are also things that are true about compact sets. As the name suggests, "compact sets" are compact. That's sort of a way of saying they are small in some sense.

Definitions and compactness

What are some definitions and why is compactness an important concept?

-

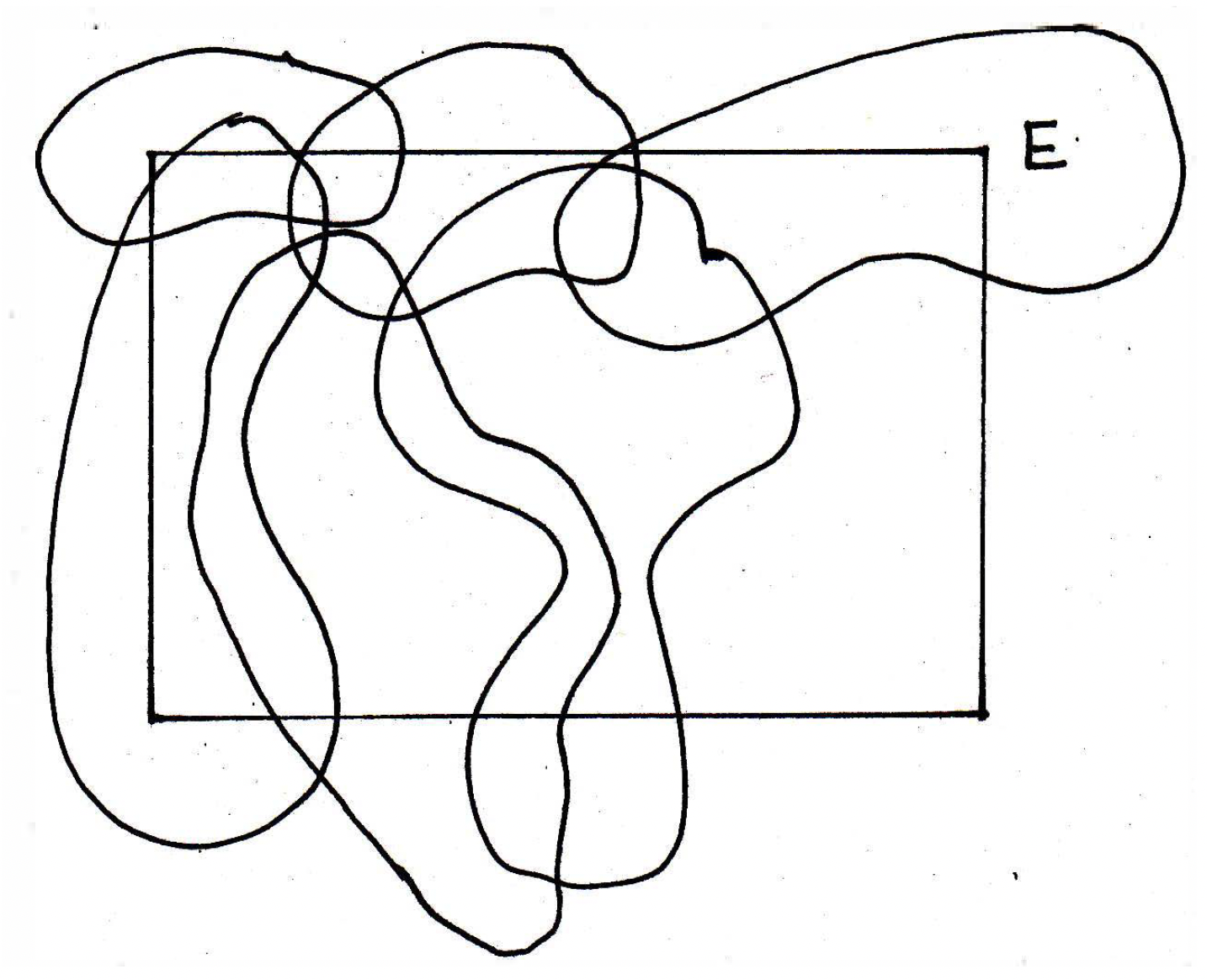

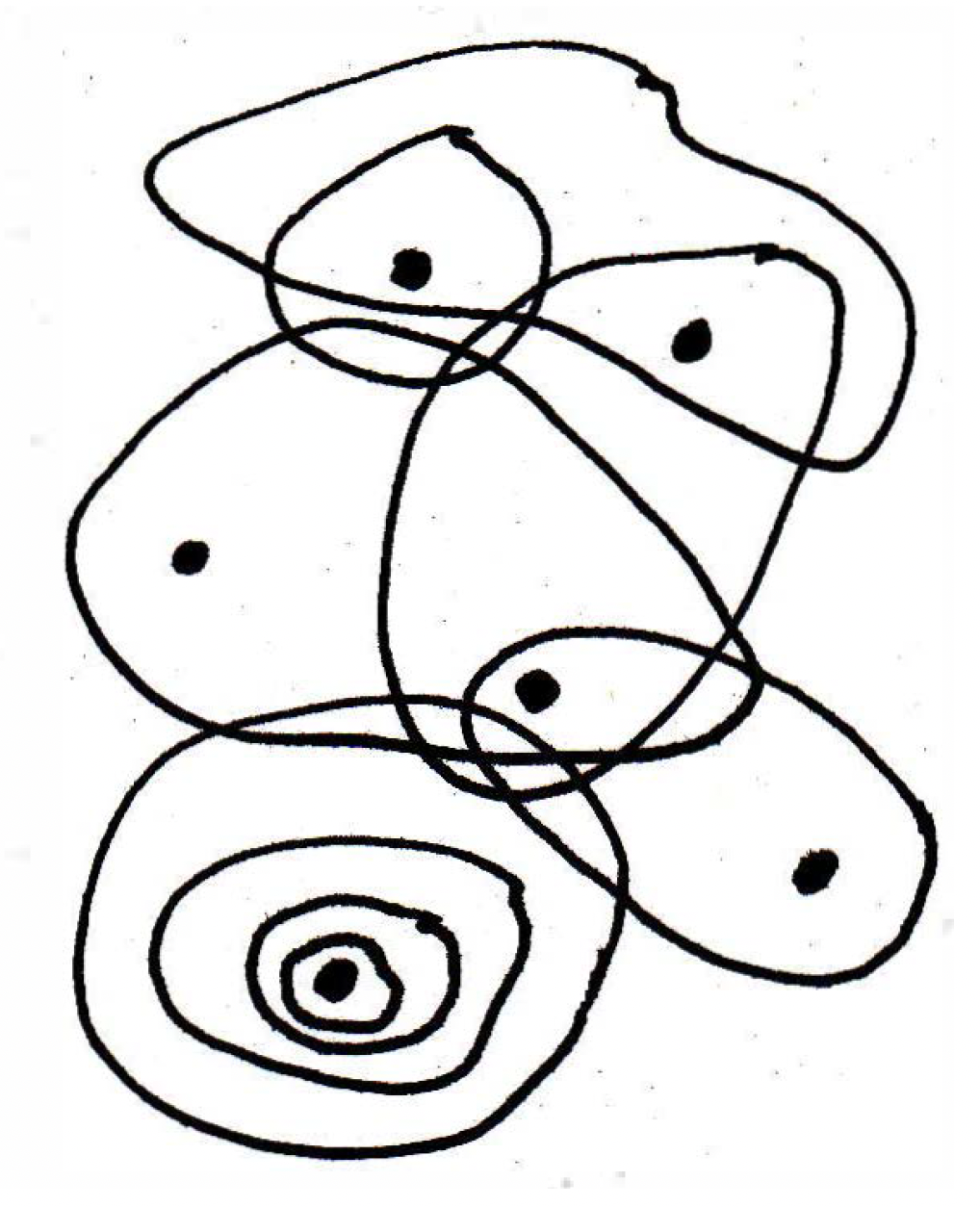

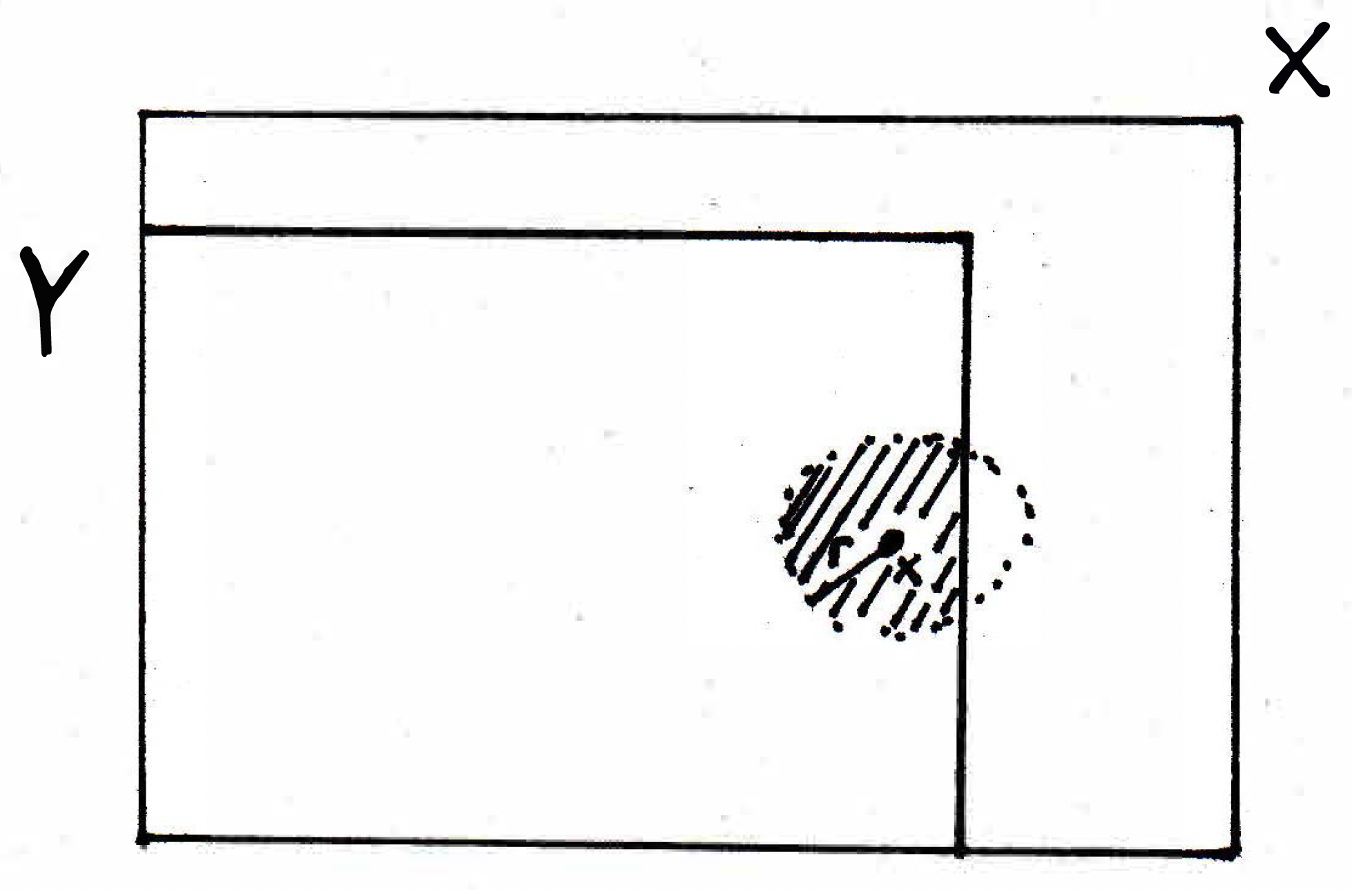

Cover (definition): The first thing we need to do is to talk about what it means to cover a set. We are going to make a definition for an open cover of a set, and as the name suggests, what do you think one might mean by the words "open cover"? An open cover is just going to be a collection of open sets that cover a particular set. By an open cover of a set in a metric space we mean a collection of open subsets of such that . Said less formally, an open cover of in is a collection of open sets whose union contains . As a note for these lectures, whenever the notation is used, it is understood that is a metric space (i.e., a set in is endowed with some metric). When drawing open sets, it is typical to draw them in a dashed fashion (i.e., you dot the boundaries of the open sets), but sometimes this is difficult to do and are thus drawn in sort of a curly or wavy way. Does the picture

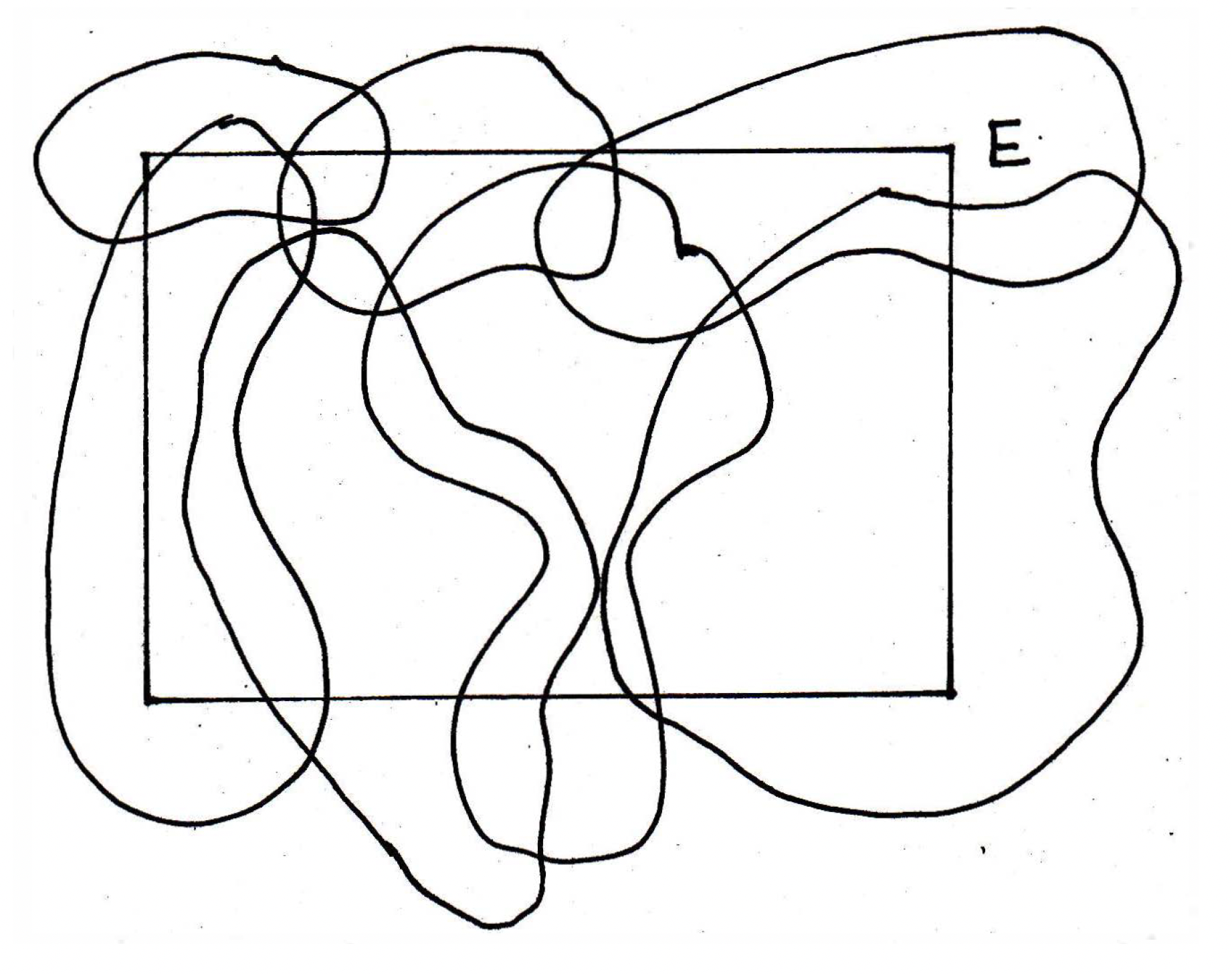

represent a cover of ? No! I've missed some points of clearly. So maybe we will throw in another open set to modify the picture like so:

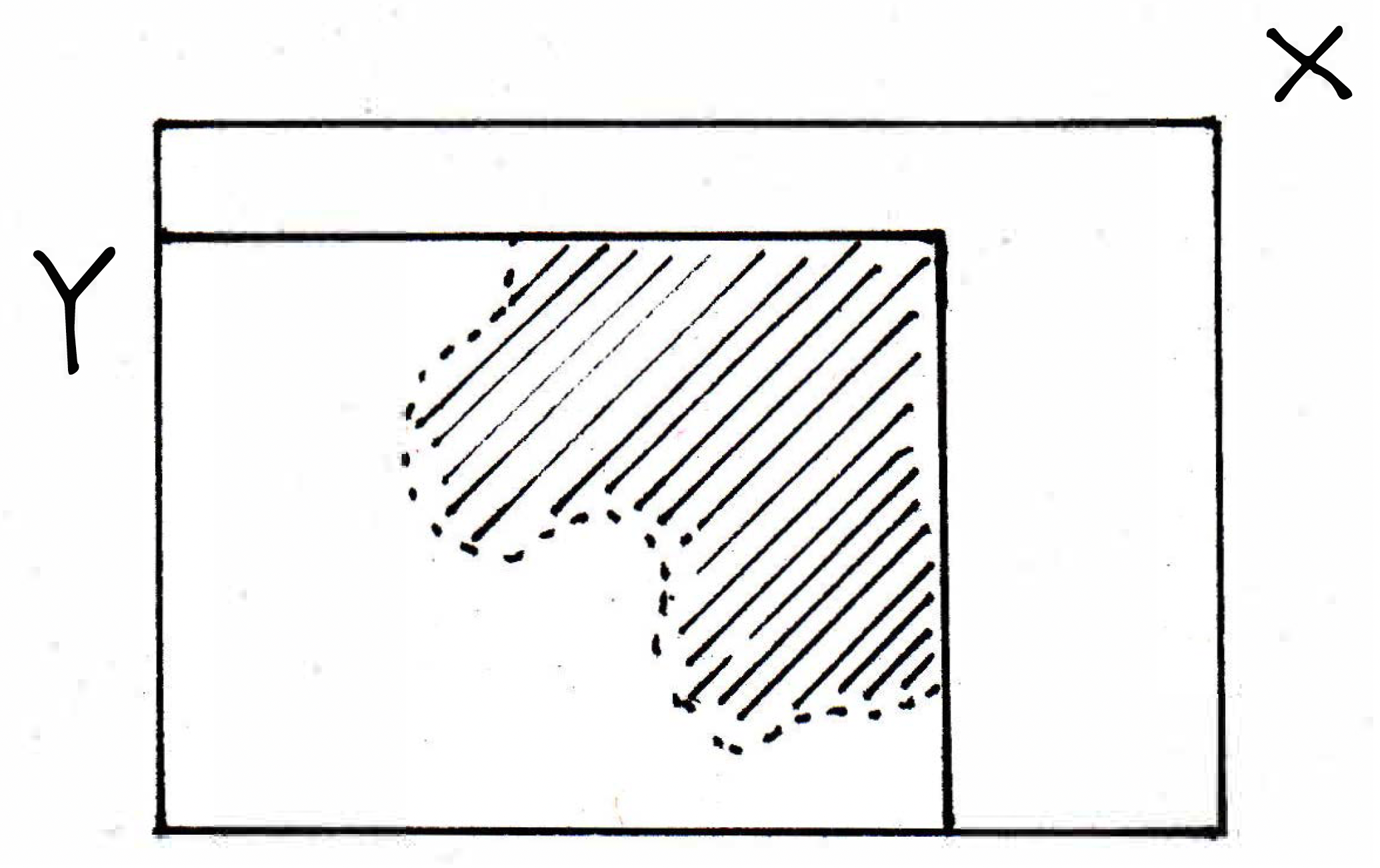

There is an open cover of now. Sometimes we just say the word cover because we are never going to talk about any other kind of cover. While we're at it, it makes sense to discuss the concept of a subcover. What is a subcover? A subcover would be a subcollection of that is still a cover. So a subcover of , where we should note that when talking about a subcover you are always referencing the open cover of which it is a subcover, is a subcollection , where this way of denoting the subcollection is chosen in such a way to make it clear that we are picking specific since may be possibly uncountable. So we might look at specific and label them with its own subscript , hence the notation . Later on, usually will just be a finite set, but this is one way to write it. To concisely recap, a subcover of is a subcollection that still covers . Now, consider the picture

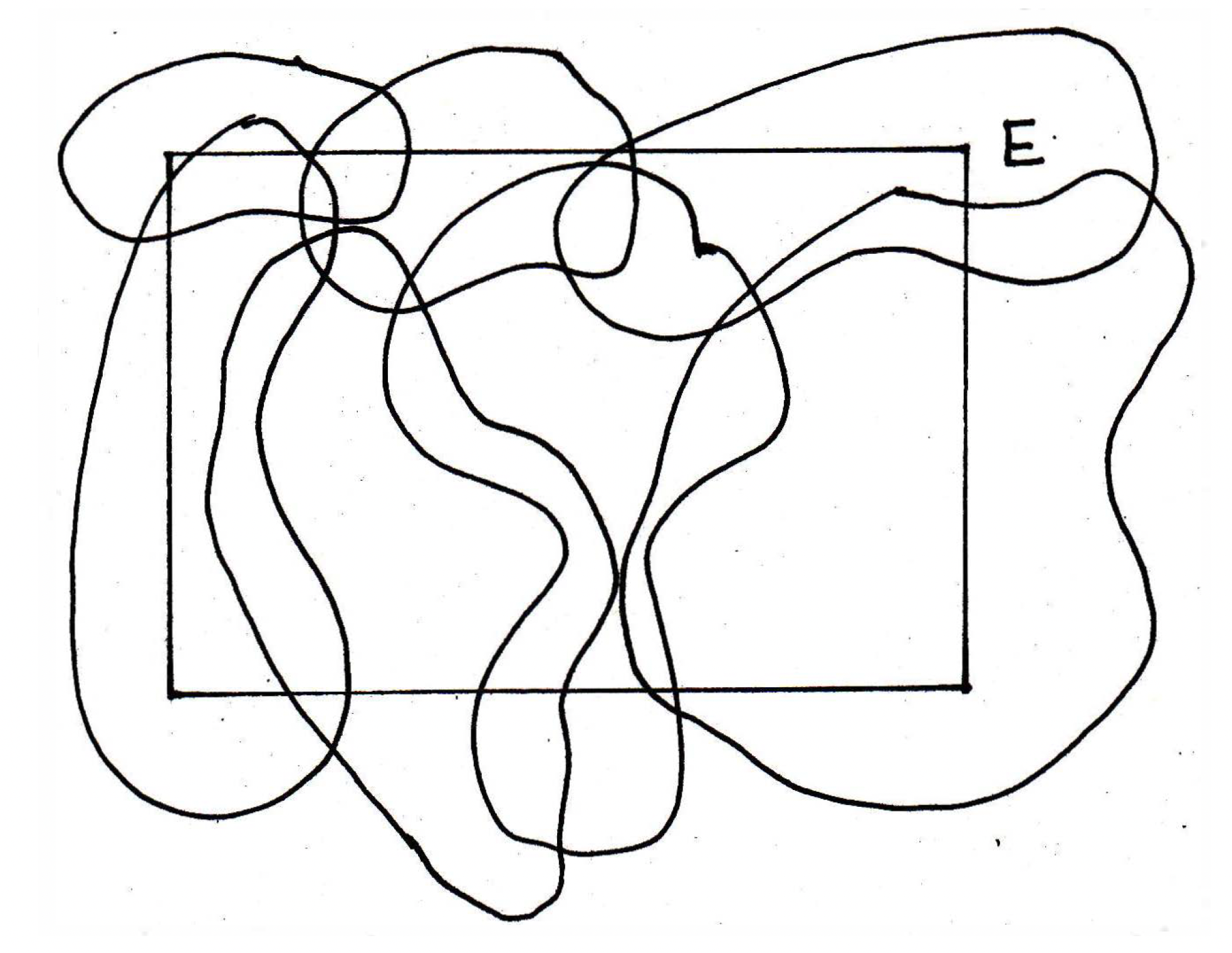

again. If I take a cover and I take the subcollection that is all the open sets, is that a subcover? Yes, it's still a subcover — it's still a cover. I haven't removed any sets. Let's thrown in another open set to modify the picture to look as follows:

Would you agree that the set just thrown in, namely the bottom right circular one, is kind of extraneous? So all of the sets do indeed form a cover, but I don't need all of them. I could throw this circular set away, and the rest would be a subcover. Let's look at some examples now.

Examples of covers, subcovers, etc.

What are some examples of covers, subcovers, and the like?

-

Example 1: In , let's look at the set , the half-open interval. We claim this set has the cover , where . Maybe we start with and keep on going. So the claim, then, is that covers the set . So what does this cover look like? The first few sets are set is . The second set is then and then

and so on. You get ever increasing intervals. Are these open sets? Is this an open cover of the set ? Yes. Why? We'll just say why. Is it clear that is covered? Yes, by all the sets. Is it clear that is covered? Yes, not by but by . And would you agree that any point just to the left of 1 eventually gets covered by one of the sets? Yes. But there are lots of covers for this set. This set also has the cover , where we note the importance of enclosing with braces to indicate that we have a collection even though this collection has only one element, namely the interval . Is this an open cover? An aside question: Do we ever need an uncountable index set? And the answer is yes for some metric spaces, although it turns out for most of the metric spaces that we care about you could have a countable subcollection. For example, here's a cover of the real numbers. Let's take all balls centered at any possible point. That's an uncountable collection of open sets. Returning to our example involving the set , this set also has the cover , where . So we have the cover here, where for every point in the set I have an open ball around that point. Basically, around every point I'm taking a ball of a particular radius. So this cover just consists of a bunch of balls around points. And how many of them are there? Uncountably many, one for every one between and 1. These are all covers, yes? So one of the questions to ask is whether or not you need everything in the cover? Above we have three different covers for the same set. Do we need all these sets? So, given a cover, do we need all the sets to still cover the set? Let's consider our coverings separately.

- For , do we need all of the sets? No. We could throw some of the open sets away. So has a subcover (many subcovers actually). How about ? Does this still cover the set?

- What about the cover ? We can't throw away the only element. So the only subcover for is the open cover itself.

- What about the cover ? Can I throw away some of these sets? How many can we throw away? So has a subcover . Would you agree this is a subcover? Not only is it a subcover but there are only finitely many elements so it is a finite subcover.

So why do we care so much about open covers? That will become apparent shortly.

-

Example 2: How about the set in (note that by mentioning we are declaring the metric space from which to choose our open sets)? Would you agree it has a cover , where and basically cover the endpoints ( goes from to while goes from to . And all the other sets look like before. Would you agree is a cover for ? Yes. Do we need all the sets to make the cover? No. Does it have a subcover that's proper? Which ones can we throw away? To clarify, does the cover have a finite subcover? No, because no matter how far you go you won't, with only finitely many sets, you will not cover everything. If you had only finitely many sets, then there's a largest index, where the largest index might be, say, 22 million. Then wouldn't cover everything. It covers all the other sets so you can throw them away, but it won't cover the endpoint. So the cover does not have a finite subcover whereas the cover does. What is one? How about ? We are ready now to make our definition for what it means for a set to be compact. With this definition, you should ask yourself why it is saying, in some sense, that such a set is "small."

Compactness

How do we define compactness and what is its significance?

-

Compactness (definition): Say a set is compact in if every open cover of contains a finite subcover. So what is this saying? It's saying that, to show that a set is compact, you want to show that every open cover has a smaller subcover that is, in fact, finite. Or, said another way, to show a set is not compact, means there exists an open cover without no finite subcover. What are some examples? Before going through an example or two, note that the definition of a compact set is not saying that there is a finite cover. Many people think the definition is saying that a set is compact if there is a finite cover. This is clearly not what we are saying because every set has a finite cover. Just take the whole metric space. Isn't that an open set?

-

Examples: Is compact? No. Because there is an open cover with no finite subcover, namely . What else is not compact? How about in ? I claim it is not compact which means you should show me an open cover for in that has no finite subcover. Can we think of an open cover of with open sets (open intervals) that clearly has no finite subcover? How about covering every integer with a little interval around it? Can you argue why this has no finite subcover? If you take any one away, you can't even remove one, without destroying its covering property (taking one away would necessarily mean an integer was not covered). So in is not compact. How about ? Does it have a finite subcover? Yes, we saw above that covers and that was a finite subcover of . Does this mean is compact? Not necessarily! Because we need to show that every open cover has a finite subcover. So may be compact, but I'd need to check every open cover. (Or prove a theorem, which is what we will do later.) It's worth mentioning that is not compact because there is an open cover with no finite subcover, namely , but that doesn't mean that there couldn't be some open cover with a finite subcover like . So to show a set is not compact, it is generally a lot easier because you just have to exhibit an open covering with no finite subcover.

-

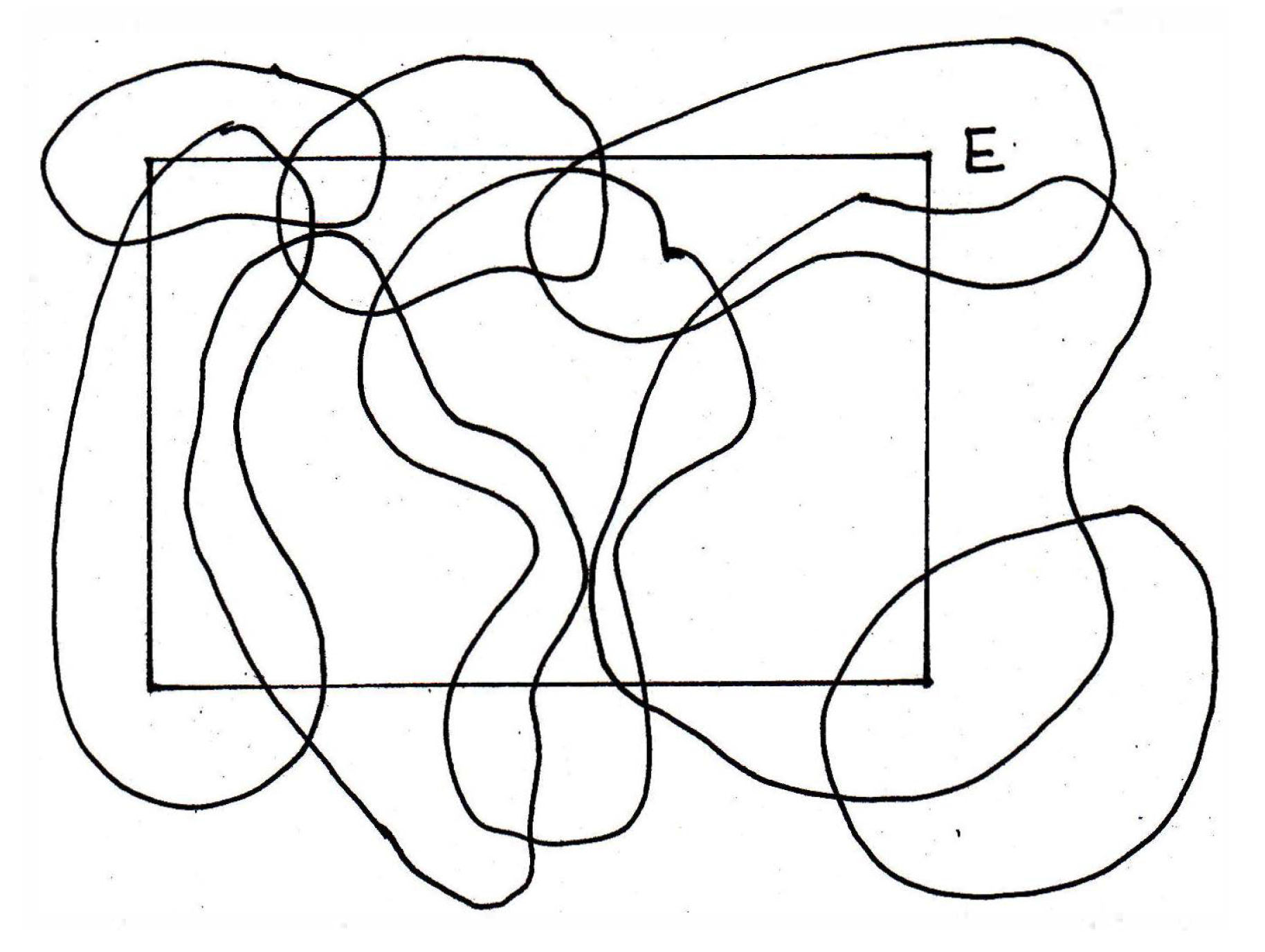

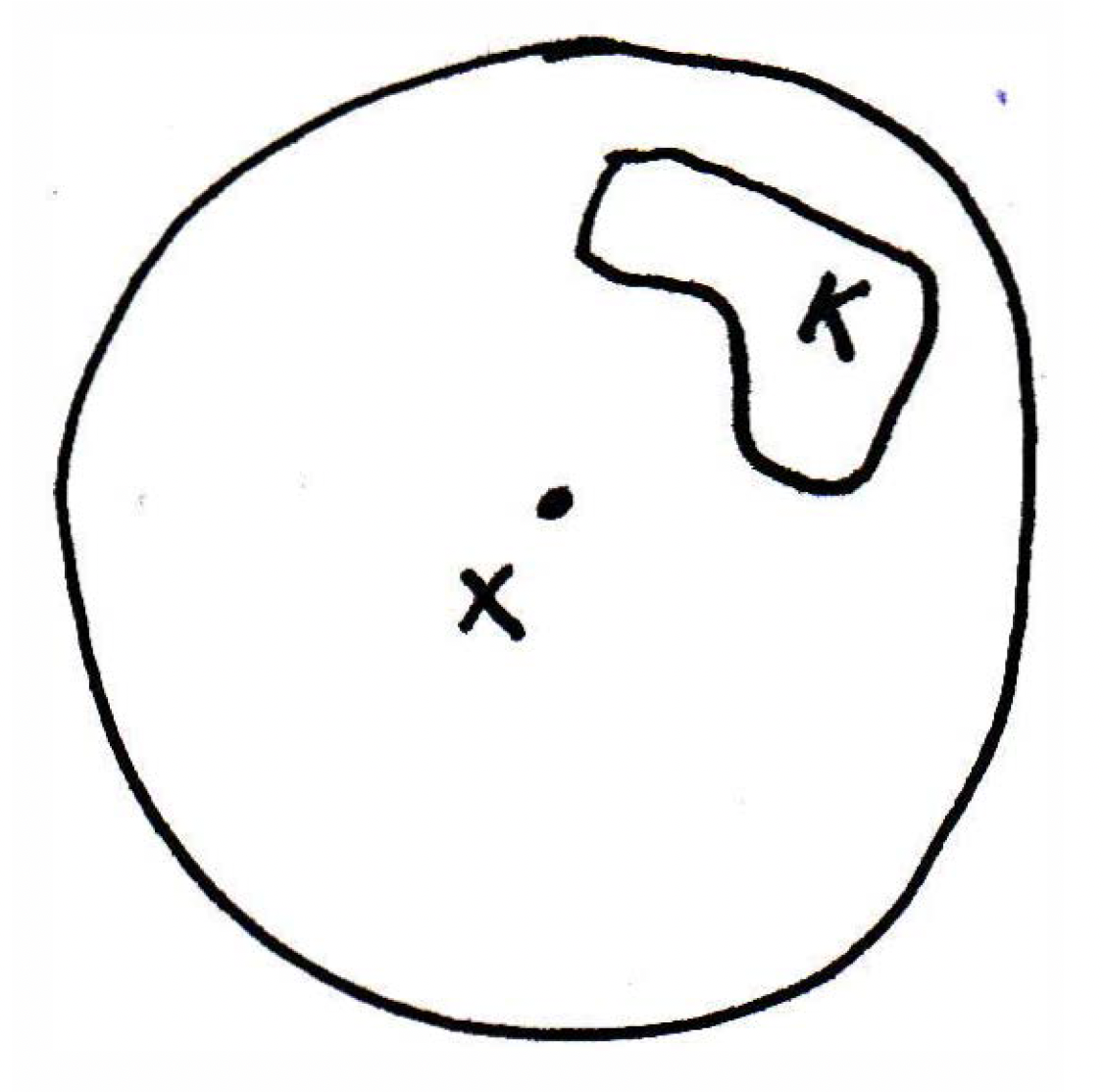

Finite sets are compact: So here's a uestion. We said something about compact sets being somehow the next best thing to being finite. It sure would be nice if finite sets were compact. Are finite sets compact? Yes. So here's a theorem: Finite sets are compact. This is actually an example where you can show every open cover has a finite subcover. Consider some open cover . Consider the following picture that has several open sets that cover the finite set:

Can someone give me an argument why an open cover for a finite set has a finite subcover? Every point could be in lots of sets, but just pick one. And you can pick one for each point. The set would then be covered, and such a covering is both a subcover and finite. So how would we write that? Consider an open cover covering . For all , choose (that is, choose one ) that contains , where is the same index. Then covers the set. What else is compact? If we can prove some things, it might give us some intuition as to what compact sets look like. We really have no intuition yet.

-

Compact sets are bounded: To show that compact sets are bounded, we first have to say what we mean by bounded. So remember we are in some metric space. Let's say a set is bounded in if there is some ball that contains the entire set; that is, is bounded if for some . (The book's definition says that is bounded if there is a real number and a point such that for all .) Consider the picture

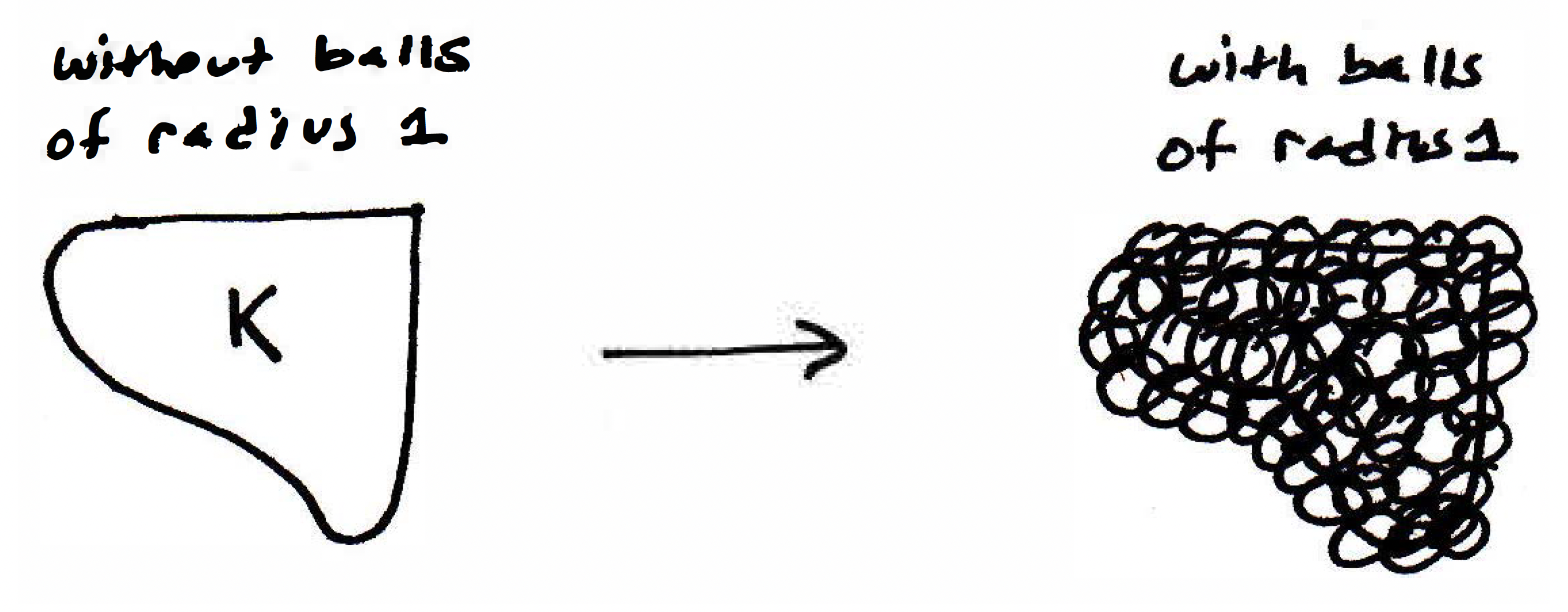

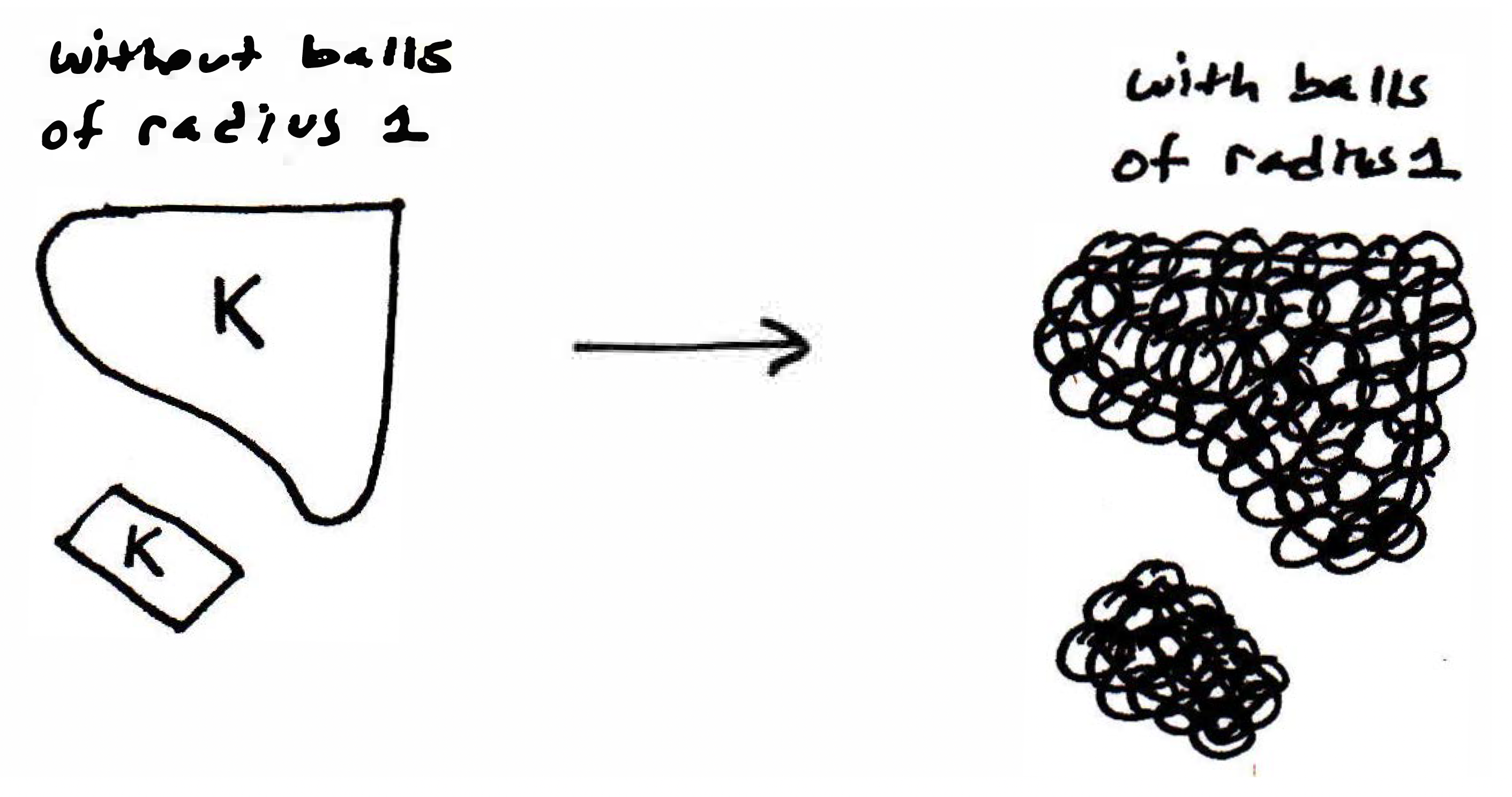

where we have a set and the ball doesn't have to be centered around any particular point in — it could just be in . This is a bounded set because it's in a big enough ball. Now let's show, in fact, that compact sets can't be too big. They're small. They're bounded. And this is somehow related to being finite, the next best thing to being finite. Okay so why is it that a compact set is bounded? Well, what do we have? What is the hypothesis now? Let's give the set a name. So here's a proof. Let be compact. Then every open cover has a finite subcover. So we can pick any open cover we want and use the fact that it will have a finite subcover. So let's pick a good open cover that will help us show that is bounded. What can we do to show that is bounded? Can we think of some open balls that cover that might be helpful? In some sense, I want to show that the distance between two points in can't be too big. So it might be helpful to cover the set with a bunch of balls of what radius? Pick one. What if we had balls of radius 1? So let's draw another picture:

If I had a bunch of balls of radius 1, then that's a lot of them, and I could use the trick we used with . What's compactness going to give you? A cover by finitely many balls of radius 1! Now why would that help you show is bounded if there are just finitely many balls of radius 1? Suppose there were now just 17 balls of radius 1 that covered . We now claim a ball of radius would cover everything or something like that. So finiteness is now playing a big role here. Because this cover has a finite number of balls that form a subcover, nothing can be more than 17 balls away. And these are all radius 1. So let's write this down.

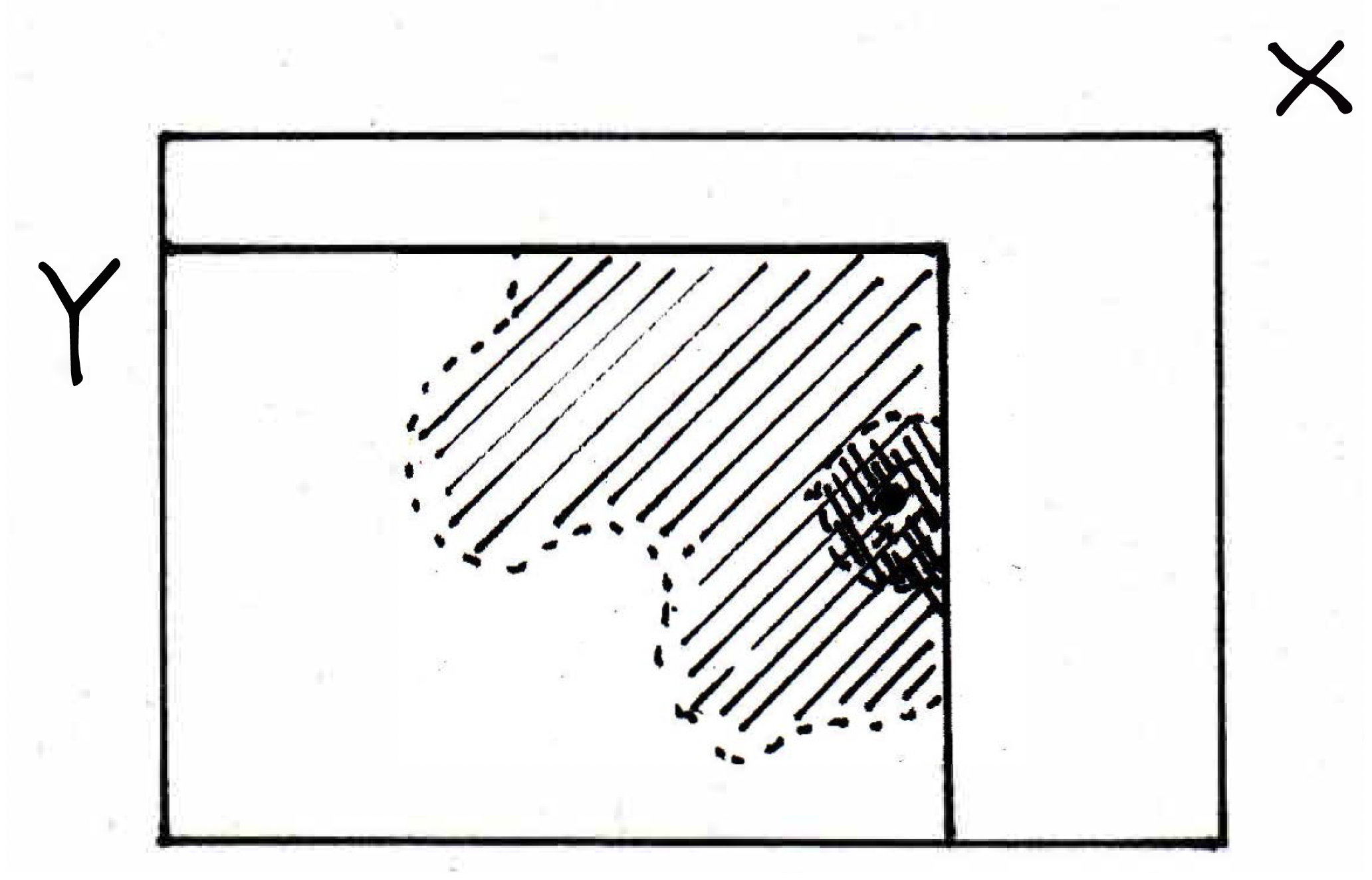

Let be compact. Let , the ball of radius 1. Then is an open cover of , which is just like the example with earlier, where we just had a ball around every single point with a particular radius, namely . By compactness of , there exists a finite subcover . What should I say now? If there were 17 sets now that covered this thing, then what's the bound? What's the center of the ball that we would use? Well, how about any point? How far apart will the other points be from one of the centers if there were 17 balls? Well, at most 17. Another way — would you agree that the set of all pairwise distances is finite? Before moving on, there is a fairly significant objection to the picture we have been working off of thus far: What if is disconnected and we had 17 balls that covered ? That's one of the problems with the crude picture we've been working with thus far:

We can represent the case when is disconnected as follows:

As indicated above, if there were 17 balls, then you might not have any relationship between some of them (namely the ones that are disconnected in some sense). So that is why we will work out another strategy for this proof because if you try to work out a proof where you do not take account of the fact that may be disconnected then your proof will fail for that exact reason or issue. So another way to do this is to look at all possible pairwise distances — how many such distances are there? Finitely many! So I can take the maximum (that number is achieved because we are dealing with a finite set). That maximum is the maximum distance between centers so then how much farther can any other two points be (imagine points on opposite ends of their balls)? The true maximum distance between any two points would be the maximum distance between centers in addition to two radii length, in this case 2 since we are dealing with unit balls. Let's formalize this.

Let , where this maximum exists because the set is finite. Then contains all of . To actually show that contains all of , you would use what? What property of metrics is going to come in handy here? The triangle inequality!

-

Recap: So what have we done? We've defined compactness in a very curious way. We have shown that compact sets are somewhat like finite sets. Finite sets are, in fact, compact. Compact sets behave in the same way finite sets do, namely that they are bounded. The concept of compactness is an intrinsic notion of the set and it doesn't matter what metric space you are in.

Compactness as an intrinsic part of a set

How is compactness an intrinsic notion of a set?

-

Motivation: We have this property of a set that we call compactness, and of course we've learned lots of other properties of sets. A set could be open. A set could be closed. One set could be dense in another set. These are all definitions that we've learned for sets in . But the notion of compactness is actually an intrinsic property to the set, and it doesn't matter what metric space you are in. That's different from some of the other notions.

-

Open sets depending on what set you are in: In , the set is open. But if we view this set as being embedded in , this set is no longer open. Not every point is an interior point. What's wrong? In , a neighborhood looks like an open interval, but in a neighborhood looks like a whole disc doesn't it? So the particular set as a subset of is no longer open. So we're looking at as a subset of , namely the subset . So openness actually depends on what set you are in. Compactness does not. Before we see that, we need to see how we relate the notions of openness in one set when it's embedded in a bigger set.

-

Relative open sets: Let's be very careful about what we mean by "open" now. We previously defined what it means for a set to be open, but now let's think a bit about the metric space that we're in. If we have a subset of a metric space , then would it not be reasonable to think that is also a metric space? Yes, whatever the metric is that is being applied in can and will be applied to a subset of . So we say that inherits a metric from . So if , where is a metric space, then inherits the metric from . So if we are going to define what we mean for a set to be open in or in , then we need to come back to the definition. A set is open if every point is an interior point. That was the definition we had earlier. But what does it mean to be interior? A point is interior if it has an open ball around it that's contained in that metric space. But now we have to worry about which metric space we are talking about. So let's talk about what it means to be an open ball.

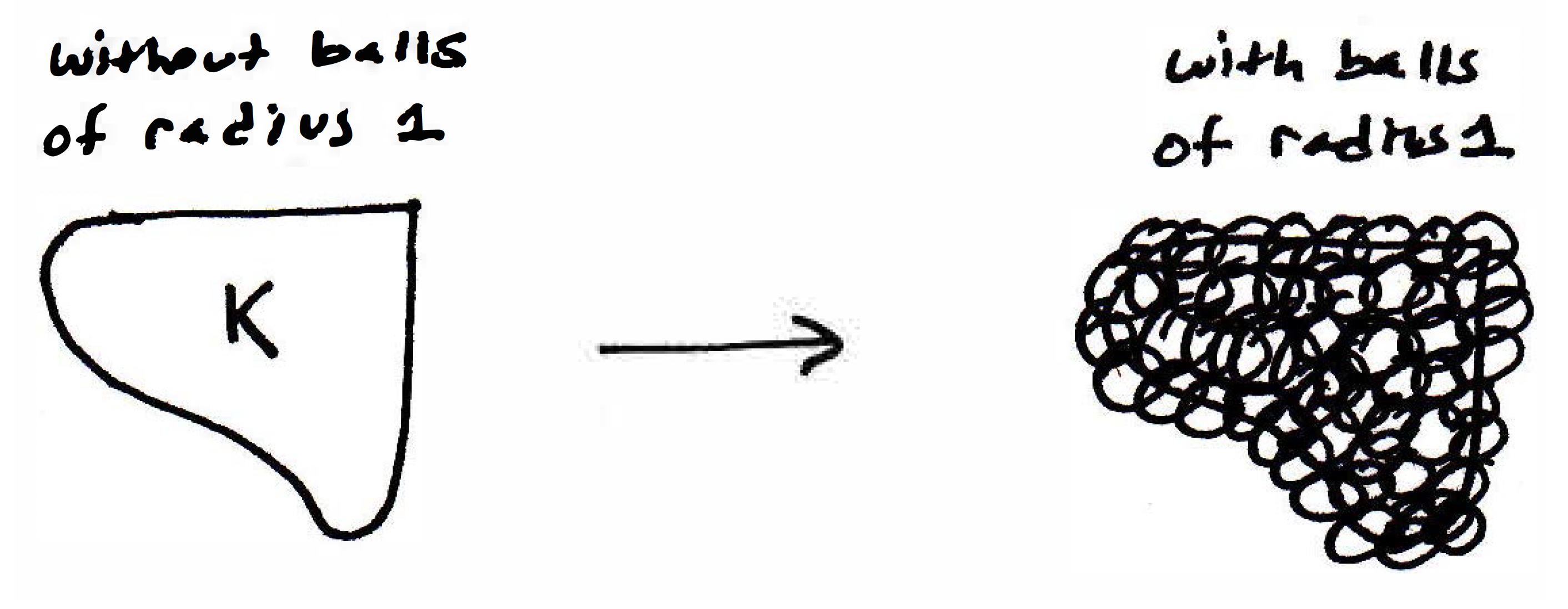

Can you see a situation where is a subset of where the notion of an open ball in and an open ball in might be different? How about the following picture:

The picture above is what an open ball in looks like, but what will an open ball in look like? Above we have in , but what will in look like? Will the open ball be smaller? Will it have a smaller radius? No, it will not have a smaller radius, but it's going to be just the stuff inside of :

So the modified picture above with the dashing is in . The difference between the pictures should be clear. So now the question remains: What's the connection between general sets that are open, not just open balls, but general sets that are open in as opposed to general sets that are open in ? So now we want to know when a set in will be open. Can we give a criterion that would help me decide when a set is open? So here's an example. Suppose we take the following set:

Is this dashed set open, where the boundary for is included? Is this set open in ? What does it mean to be open in ? It means that every point is an interior point. Consider the following picture:

Is the illustrated point an interior point? Yes, because it has a ball around it in that's still open. This is the open ball around that is in . That point is an interior point. What's a point that might not be interior? A point on the edge? Consider the following picture:

This added point has an open ball around it that's contained — in ! Are we now convinced that the originally drawn set

is open in ? Do you agree that it has neighborhoods, it's just that you forget everything outside, and what remains are all the points in a distance from . So the pictured set is, in fact, open in . Is it open in ? No. But is there a relationship between sets that are open in and sets that are open in ? Yes, the claim is that there is, a very nice criterion in fact. And the criterion is that a set is open in if and only if there exists a set in

that is open whose intersection with is this given set. We'll give this set a name. We'll call it . Before stating the theorem, let's just make an important definition: A set is open in ("relative to ") if every point of is an interior point of . Of course, the key difference here is that the notion of interior means using neighborhoods in , using those kinds of funny, possibly half cut off discs. This is no different from the definition we had before; we're just paying particularly close attention to what set we are living in. So the metric space matters for the concept of openness. So here's a theorem:

Theorem. Suppose . Then is open in if and only if for some open in . (See the picture below.)

This is a very nice criterion because it allows us to pass between open sets in one space and open sets in a bigger space. Does this seem believable? It's an if and only if so here's a proof idea. One direction should be fairly clear. Would you agree that if you have a set then its intersection with has got to be open in ? Why? What does it mean to be open in ? Well, it means every point has a neighborhood around it in that's also in . So in , what's the neighborhood you're going to use? The same one, but just restricted to !

To say something's an interior point you're referring to a particular set. So the claim is that if is interior to , then it's interior to using possibly cut-off neighborhoods. That's basically using this correspondence between neighborhoods in and neighborhoods in . So the proof idea in the backwards direction uses the fact that if then is the neighborhood of .

What about the forward direction? If a set is open, then that means around every point there's a neighborhood, but possibly a cut-off neighborhood, that's in . Can you think of a set that would also then be open? Suppose you have a bunch of cut-off neighborhoods. What could you do with those neighborhoods? Include the stuff that it suggests! And then what will the set be? Define . Union all these neighborhoods! So if I missed a part, then include it:

So then why is the union of a bunch of open balls open? Well, by definition, because every point now has a neighborhood that shows it's interior. So if is open in then every point has a neighborhood . Then in is open. Call it . Then we are done.

The upshot of all of this is that I can tell when a set is open in a smaller space just by seeing if it's the intersection of something from the bigger space that's also open. What we want to do next time is show that if a set is compact in , then it's equivalent to saying that is compact in . So compactness really doesn't depend on the metric space that you're in (as opposed to openness which clearly does). To say that a set is small really does not depend on the metric space that you're in. And then when want to show some other analogies with finite sets.