7 - Countable and uncountable sets

Counting sets of real numbers

After building up some introduction to the real numbers our goal now is to be able to count sets of real numbers. How might we start to be able to do this?

-

Counting in general: To get start with this goal, we have to lay a groundwork for the idea of counting. In the Sesame street video, the questions come up as to why we both to count and how is it that we actually count. So if I wanted to count a bunch of fish, and I wasn't going to use a number to describe how many fish I had, I might do like the figure in Sesame street: "Fish, fish fish; fish, fish fish." But there's a problem with that. It is actually kind of hard if you have 52 fish to count to list them all out. So what is it we are doing when we count? For instance, if I count the people in the first row, "1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6" (i.e., fish, fish, fish, fish, fish, fish). Or if I'm a baby and I want to count the number of toes I have, I might lie down in the supine position and count my toes. What am I doing? What is it I am doing? I am assigning a number to each object. And not just any kind of number either. A natural number! What if I counted out of order and counted someone twice? We wouldn't be happy with that method either, mostly because of counting something twice. For a satisfactory counting method, we are mapping the people in the first row onto the natural numbers. And that's in fact described formally by a function. So the first thing we have to do is remind ourselves about functions. We write to signify that elements in are getting mapped to elements into or simply saying, " maps into ." We say "maps" or associates in the sense that each in is uniquely associated to some element in . Here the set is called the domain of the function while is called the codomain. Now, if and , then we'll define . This is called "the image" of which lives in . We can also define a similar notion of going backwards, from codomain to domain. We might call such a thing the inverse image of . We would write , where the in the notation may be thought of as "going backwards" in the same sense that a negative number in general is often meant to indicate a change in direction or reversal. When , then the codomain is the range. When the range is the entire codomain, we say is onto or that is a surjection. When implies that , we say that is one-to-one or injective. When is one-to-one and onto, we call a bijection.

-

Mathematical shorthand for special functions: If we are dealing with surjections and injections and doing so in a nonformal way (it's rather bad form to use this in actual writing), then we might write to communicate a surjection and to indicate an injection. We would then write to communicate a bijection. If you have a bijection, then this bijection is a function whose inverse will also be a function. Each element in is mapped to a unique element in , and, in turn, each element in is mapped to a unique element in . And the problem with the earlier counting example of counting someone twice or something like that was we were not happy unless our function was a bijection. More specifically, if there are more people than 3 in the first row and all I say is "1,2,3," then this function is not onto and thus not bijective. And if I counted someone more than once, then the function is not injective because two numbers are being mapped to the same person. When is a bijection, then we say that and are in one-to-one correspondence. We might also write to communicate that and are in one-to-one correspondence. So what's the point of one-to-one correspondences? It's a way of saying the number of elements in is equivalent to the number of elements in even though we really haven't defined what we mean by "number." But in an intuitive way it makes sense because means that I can take all of the elements of and associate each one with a unique element in and vice-verse. And previously, when counting out `1,2,3,4,5,6," what kind of numbers were we using to map to other objects? We were using a subset of the natural numbers.

-

Elementary counting: I am using as one of my subsets , a subset of the natural numbers. In the above case, we would have . Is this not what we do when we count? Isn't this what a baby does when it counts the number of toes on her foot? We now have a very nice way of associating numbers, natural numbers anyway, with somehow the notion of size of a set. So now if you give me a set, then I can count it. How can I count it? Well maybe we have the set . Can I count the things in this set? Sure. There are many ways. A natural way is to simply write out 1, 2, 3, 4. But there's nothing to stop me from counting them in a different order, perhaps

So I am associating to the function described above that corresponds to whatever the set is called. So maybe above we have and we write to communicate that we are associating with a set one of the initial segments of natural numbers, namely the segment . So we've made a start here. Now if I want to talk about the size of I might say that the size of , which will often be denoted by absolute values, is . Is it possible to associate to every set a natural number in this way? Is the "size" or "cardinality" definition well-defined? It's not clear from the definition, where the definition was to find a one-to-one correspondence between a given set and a subset of natural numbers. How do we know there is no other one-to-one correspondence where we get 5, for instance, by the time you're done? So that's a question to worry about. And even if that question is settled, then another potential question concerns whether or not there are other sets where it's not possible to find a one-to-one correspondence with some initial segment of natural numbers? If you can find such an association, then we will call such sets finite. More precisely, we will call a set finite if for some . (The set is considered to be finite.); otherwise, the set is infinite.

-

On whether or not the set of natural numbers is infinite: Let's explore a few things about . There's a special situation where you might worry about one-to-one correspondences and that is in the case where you have , where it's no longer elementary counting where — it's counting where is all of the natural numbers. We haven't yet established whether or not natural numbers are infinite, but let's go ahead and make a special definition. We'll call countable if can be put into one-to-one correspondence with the natural numbers? We might ask ourselves whether or not there is any difference between the definitions

"Call finite if ; otherwise, is called infinite."

and

"Call countable if ."

Let's just see what things are countable first of all. Would you say the natural numbers themselves are countable? Yes, of course. If you say that something is countable, then you need to describe the bijection that achieves the one-to-one correspondence between the set in question and , mathematically in terms of a formula or an unambiguous verbal description. What bijection would you use between the natural numbers and itself? We have , but what is the bijection? Simply let . So itself is countable.

-

Countability in terms of sequences: Let's now look at the possibility of sequences being countable. Let's look at the sequence of distinct terms. Is this countable? Why? We could describe this by writing . This provides a function that provides a bijection. Any sequence indexed by the natural numbers is countable almost by definition because you can basically see the bijection. The moral of the story is that if you have a set of numbers or objects that can be listed in a sequence then the set is countable. What else has to be countable? What about the sequence ? Yes! What's the bijection? We could use . Now what about the set . Is this countable? Yes! What's the bijection? Let

Now, would you agree that if you can see the listing, then, if someone forced you, you could write down the explicit bijection. I claim now that we have just enough to show that a countable set is not finite.

-

A finite set is not countable: The set , or any countable set for that matter, is infinite. How might we show this? We're going to prove this, as we often do when we have no insight about something involving the natural numbers, by induction. What are we going to induct on? We are going to induct on and show that is not in one-to-one correspondence to any ; that is, . For the base case, is it clear that there is no bijection between the empty set (or even the set with one element) and the natural numbers. More specifically, if is bijective with the set , then clearly 1 gets mapped to somewhere in . So consider ; then consider . It's nonempty. So is not onto. Or the other way to say it, if you are looking at the forward function, could not be one-to-one because everything has to get mapped to 1. Okay so what's the inductive step? It goes like this. I am going to show you that if there were some secret bijection between and a segment then there would be another secret bijection between and the segment with one less number in it. More precisely, we will show that if is bijective with , then is bijective with . That is, if , then . If there were a bijection , then what could we do with this? I claim that now I can construct a bijection between and . How will we do that? Well, . So what's going to happen? If we have the bijection , then there would exist a bijection . We claim also there is a bijection by virtue of the previous example. Since we have the bijections

we gain another bijection by the composition , namely

So what I've shown is that if there were a secret bijection , then there is a bijection . So we have just established the inductive step. So there exists a bijection . That establishes the inductive step because the claim was there is no bijection . The base case was there was no bijection , and this is now showing that if there is no bijection then there is no bijection . (And this is the contrapositive of what we showed in the inductive step, namely that if then .)

So what's the key idea here? The key idea here is that is infinite, and the way we showed it was because it can be put into one-to-one correspondence with a subset of itself, which is actually a very surprising fact. At first blush, it seems really ridiculous. How can you have a set that, in some sense, has the same size as a subset of itself (and a proper subset at that!). And it turns out that that is actually something that characterizes infinite sets. You can show that a set is infinite if and only if it can be put into one-to-one correspondence with a proper subset of itself.

-

One-to-one correspondence between and : Perhaps even more dramatically than the example above, I claim that I could put the set of natural numbers into a one-to-one correspondence with the set of even natural numbers; that is, I claim there exists a bijection such that . So how would you show this? What's the bijection then? What's the correspondence or association? Use . So and have the same size or cardinality. The upshot of all of this is that we have shown that countable sets do exist and that they are definitely different than finite sets in a very interesting way.

Countability arguments and standard number systems

How might countability arguments apply to standard number systems?

-

Countability and : Can we come up with a bijection to show that is countable? What would the association be? Instead of writing it out explicit, we could start with something like and write

This pattern certainly seems like we could continue it indefinitely, and if we were forced to then we could probably write down an explicit description of our bijection. So is, in fact, a countable set. Rudin gives the explicit description

So is countable, is countable. What about ? We could use the same ideas. One might be tempted to say that all subsets of countable sets are countable. And such a temptation turns out to be good because it's mostly true — every infinite subset of a countable set is countable. This turns out to be a rather helpful lemma oftentimes because it means we can avoid having to come up with explicit descriptions of our bijections as we have done thus far.

-

Every infinite subset of a countable set is countable: So what's the basic idea? The full proof appears in [17], but here's the idea: The idea is to suppose that is countable where we can think of , where this set is countable. Now we pick off a subset of this, where maybe , , and some other elements are in the subset but not necessarily everything is in it. But this subset is infinite. What can we do? Your task now is to list the things in . How will you do that? Let be the first index that appears or, more precisely, . This will denote , and why does this infimum exist? It's bounded below? Real numbers can be bounded below but not have a smallest element. But we have a set of natural numbers and is well-ordered so non-empty subset of has a least element. So exists by the \wop. So we are wanting to write , but what might be in this case? It should be the next thing in so if we picked off after in our construction of , then should be the third element of that is picked off. More specifically, . And, in general, we can let . So we have a listing for , namely . This is the idea. And this lemma will become very very useful.

-

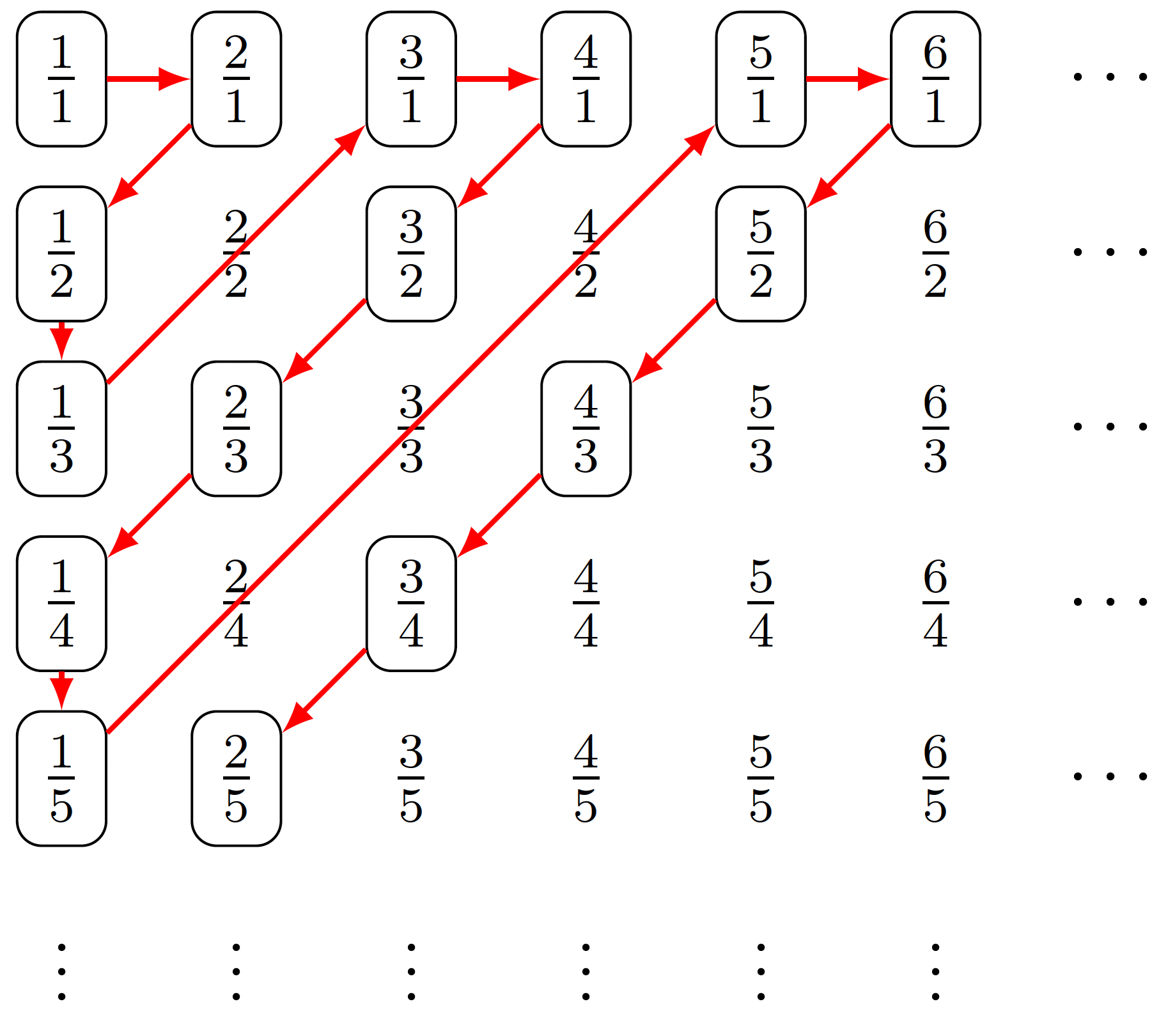

Countability and the : Is countable? I'm going to write the rationals as ordered pairs. More specifically, we get something that looks as follows:

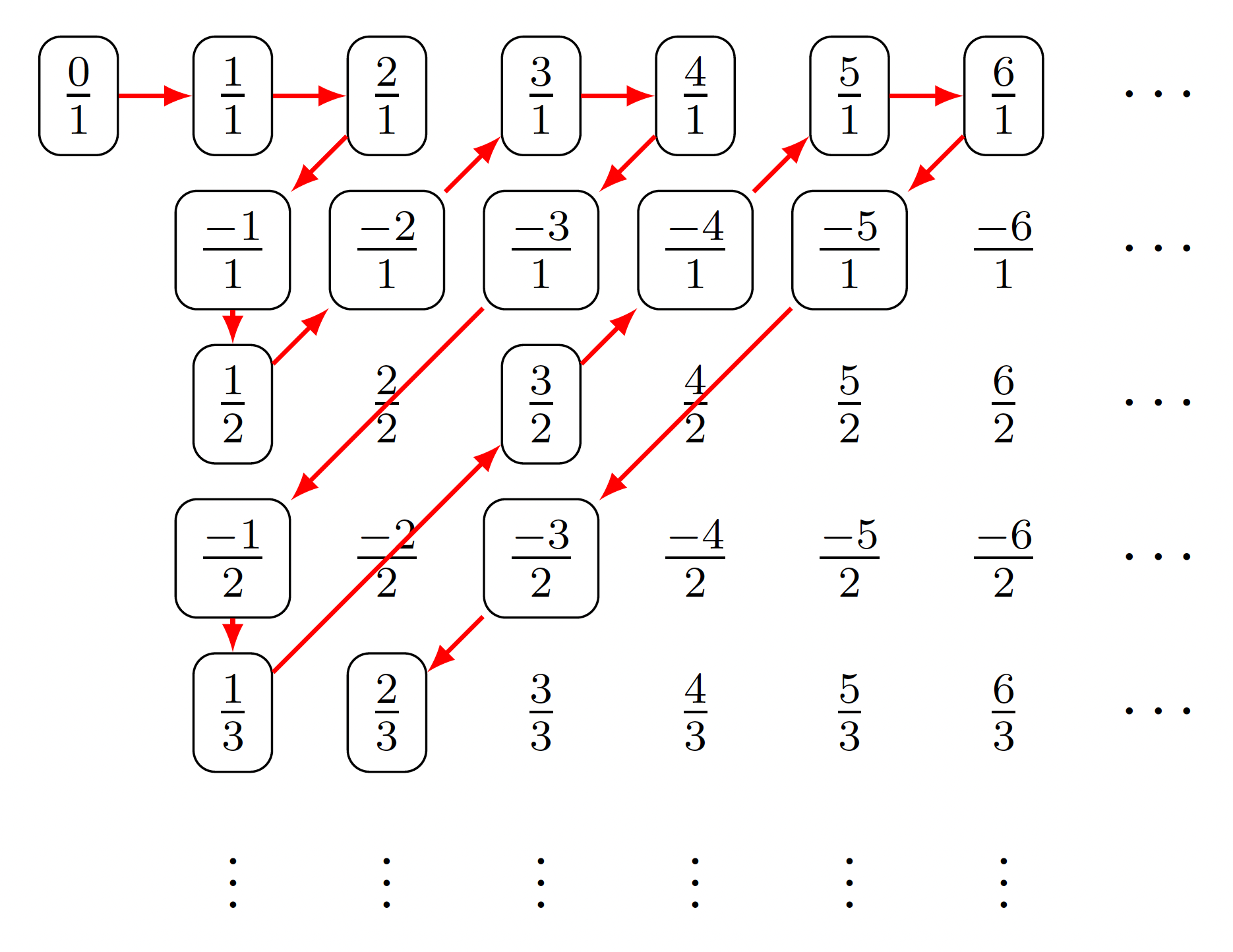

It's clear that every positive rational will appear in this array at some point. Now all I have to do is list them in some order, indicated with the red arrows above. One issue we might worry about is that some rationals repeat, but this will not be a problem. Why? What we have really shown with our diagonalization argument is that ordered pairs of natural numbers are countable and the rationals are just a subset of them where you pick 1 representative of them to be in the picture. In the figure above, where red arrows are included, representatives have a bubble around them whereas non-representatives do not. The whole set of positive rationals is a countable set so any infinite subset will be a countable set as well. So we have shown that is countable, but we have really also shown that if is countable then is countable. The above is really a demonstration that is countable, but if I wanted to show that is countable, how could I do it? I'd use the "trick" we used for , namely having all of the nonnegative rationals going one way and all the negative rationals going the other way and associate the natural numbers with them in an appropriate fashion. That produces a biinfinite sequence, but that can be put in sequence by now picking 0 off first, and then 1 and then and swinging back and forth. (It may help to think of appending a rope to 0, then to 1, then to , then to 2 and so forth — once the rope is pulled out, all the rationals are attached to it.) We could also modify the above presentation as follows:

Actually, more generally, the book shows that not only are ordered pairs countable but ordered triples are countable as well. And ordered quadruples. And so on by induction. So we now know that is countable and a next reasonable consideration would be the set of real numbers.

-

Countability concerning : Is the set countable? Can we list all the real numbers? If the answer is yes, then we simply produce a listing. If the answer is no, then you have to show that any listing you try will fail to hit everything. Let's just suppose for right now that there were some listing, and let's see if we run into some problems. Here is a proposed listing:

Now, I claim that if you look at this list then I can produce a number on the right-hand side that isn't in this listing in a very special way. Our proof that is uncountable will be a proof by contradiction that will begin by assuming that there is a listing. Suppose there exists a bijection (e.g., look at the illustration above). We will show that the bijection is not onto, thereby establishing that the proposed bijection is really not a bijection at all. And this will be a general proof that will hold for any proposed listing, not just the listing I have above. I just have to show you what to do with any such listing. And we'll do it by example. So I am going to produce a real number that doesn't appear anywhere on the listing suggested above. And the way I am going to do that is I am going to make sure that this number disagrees with every number in our listing in some decimal place. How am I going to do that? I will produce a number that disagrees with the first number in the first decimal place, the second number in the second decimal place, and so forth:

And the way I will do that is by looking at the th digit of the th number and if it is a 7, then I will make it a 1, and if it is not a 7, then I will make it a 7: For example, according to the scheme above, our number would start off as follows:

The claim is that for any . Why is this the case? Why is this number , which we've constructed and basically made different from every number on the list, not going to be on the list? The number differs from in the th decimal place. So is not in the image of . So we have a set that is somehow bigger than the set of natural numbers in the sense that it cannot be put into one-to-one correspondence with the natural numbers. How come this proof does not prove that the rationals are not countable? This proof would not work to show that the rationals are not countable because that would demand that everything on the right side in the scheme above be a rational number, and yes you could produce a number that is not on the list, but there's no guarantee that that number is rational. So it wouldn't disprove anything. So, in fact, is uncountable. So this leads to a notion of the size of sets.

-

The sizes of sets: We have sets of different cardinalities. There's , , , \ldots, , which are finite sets, but then we also have the natural numbers which happen to have the same cardinality as . But then there's also which is not in the same category as and . Are there other sets with other cardinalities? The answer is yes — there are actually infinitely many cardinalities. A theorem goes as follows: For any , we have , the power set of . What is the power set of ? It is the set of all subsets of . The argument for the rationals can be used here; that is, the proof is a diagonalization argument. It looks very similar to the Cantor diagonalization argument. The consequence of this particular fact is that if you look at the set of all functions , that's a much larger size of an infinite set than the real numbers because it's basically a power set of the real numbers and you could just keep going if you want. There is a question as to whether or not there's a size of infinity between and . And it turns out that that question is provably undecidable. That means you could the answer to that question to be true or false and not violate the mathematics as we know it. That's a rather surprising fact, and that's called the continuum hypothesis.