13 - Compactness and the Heine-Borel theorem

The Heine-Borel theorem

What more can we do with compactness? What will the Heine-Borel theorem do exactly?

-

Compactness: We've shown why compactness is such an important concept, but we haven't yet shown beyond a finite set any other sets that are compact. Finite sets are compact, but today we are going to prove that the closed interval is compact. And then we're going to show that if you're talking about points in or that closed and bounded sets are compact. That's the Heine-Borel theorem. And then we'll prove some other theorems about compactness as well.

-

Recap: What are some results that we've shown about compactness to this point?

- Boundedness: We've shown that compact sets are bounded. Let's try to recall why this was true. Well, the idea is to show that the compact set's contained in some ball. And what ball did we place a compact set in if we know that every cover has a finite subcover? Take balls of radius 1 and then what? There's a concern with taking maximum radius between centers of any two balls unless you have how many balls? Finitely many. How do we know that there are finite many balls? Compactness gives us a finite subcover of the cover of all balls of radius 1. Then we can take a maximum because there is only a finite number of things to check. In fact, just take 1 center, look at the maximum distance to any other center, and then add 2 to account for the balls around. That's the picture you should have in your head, and we used finiteness in a very essential way here, which shouldn't surprise us because that's the whole point of compact sets. They're the next best thing to being finite.

- Closure: Compact sets are closed. This is true in any metric space. The proofs we had worked in any metric space. What's the picture proof here? Take a compact set, take a point not in the set, and show that that point is what? Not a limit point. Which is the same as showing that it has a ball around it that separates it from the original compact set. How did we find that ball? Take a point in the set and the center point of the ball. And so there are partner sets between every point in the set and the center point of the ball. So the set of all such partner sets, many of those cover the original compact set. That's a cover. Because that set was compact, it has a finite subcover, and you look at the partner sets of the sets that make up the finite subcover of the compact set, and there are only finitely many, and take their intersection.

- Containment: Closed subsets of compact sets are compact.

- Nested interval property: This isn't about compactness, but it's useful, especially in what will be the proof of the Heine-Borel theorem today. It says that if you have nested intervals of closed sets in the real line, then the intersection of all these closed sets is nonempty. Note that this isn't true for all closed sets. It is a statement about closed intervals. Why isn't it true for all closed sets? That is, if we have nested closed sets, then why are we not guaranteed that their intersection is nonempty? What if we had closed rays going like , , , etc. Are these nested? Yes. Does their intersection have anything in it? No. So the nested interval property is not true for arbitrary closed sets, but it is true for closed intervals.

-

Closed intervals are compact: We want to show that is compact, where . This will hopefully give us our first large class of sets that are known to be compact in the real line. As an aside, this result will also be true for -cells in . Now, how are we going to prove that is compact? We must prove that any open cover has a finite subcover. Now, that's a lot of open covers to check! We could try to start that way, but here's another strategy for proving that is compact. We could prove this by contradiction. How would that go?

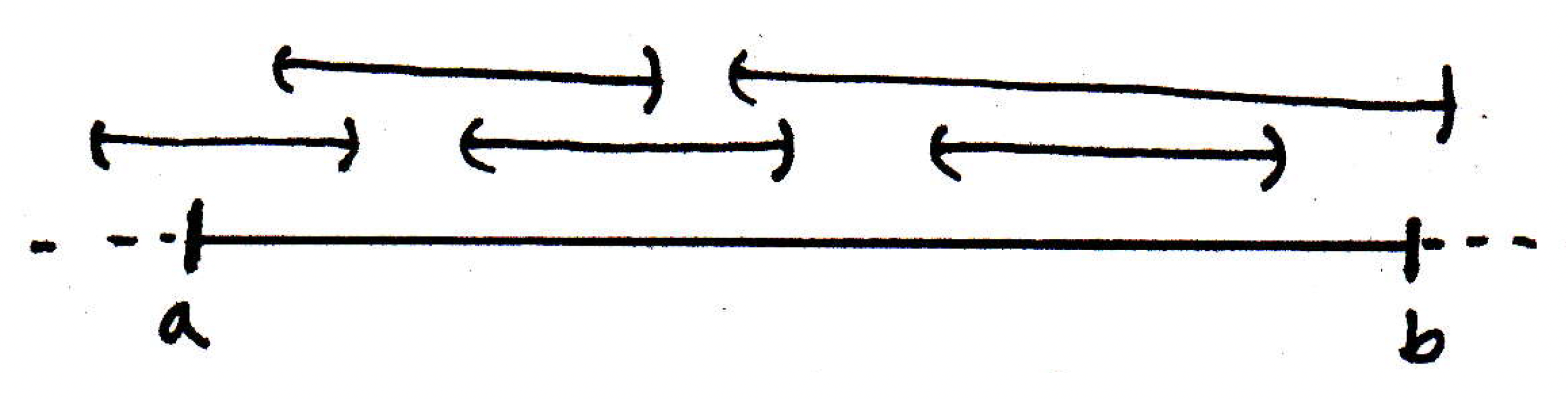

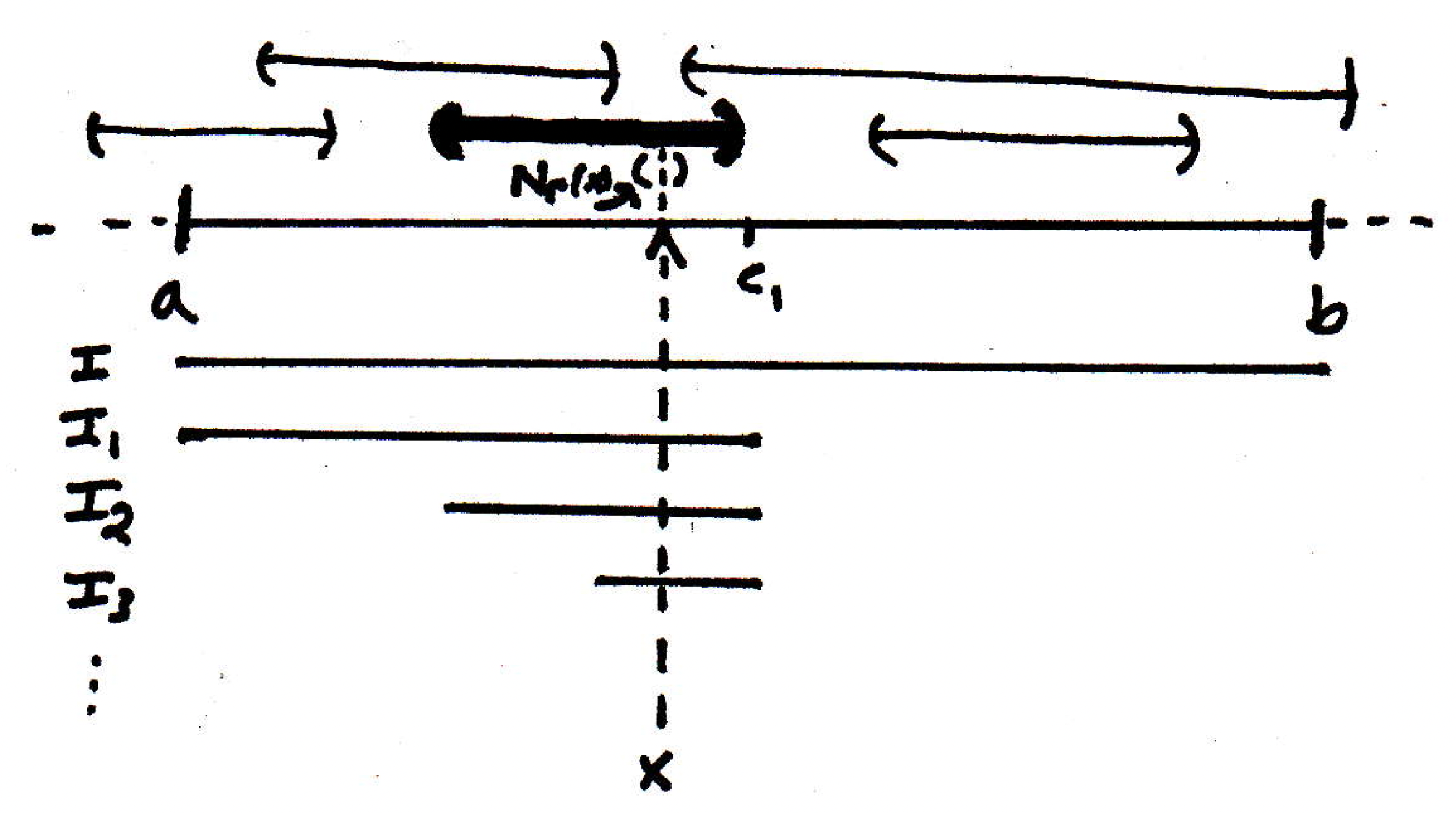

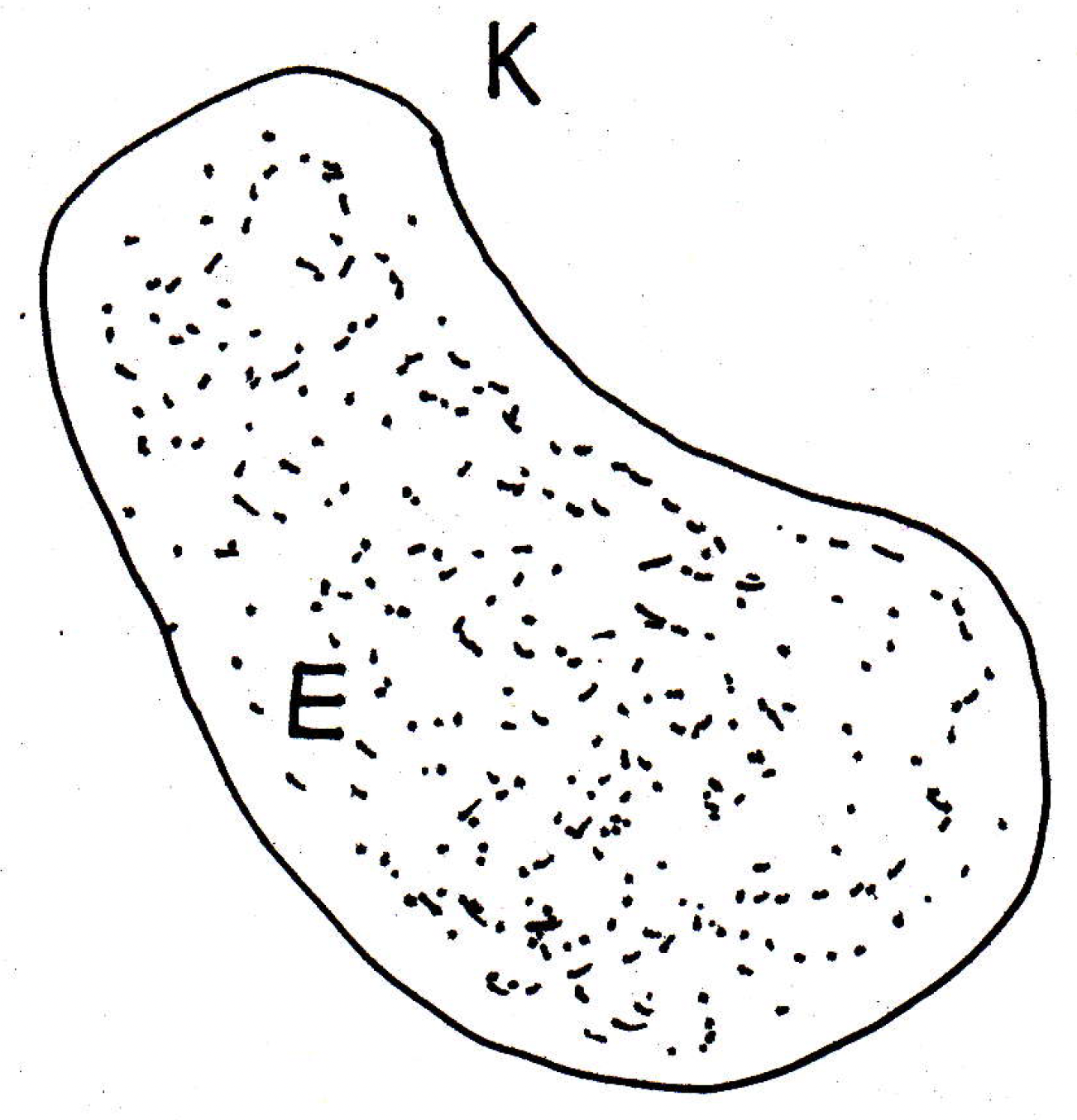

Suppose is not compact. That would mean there exists an open cover that has no finite subcover. The nice thing about starting this way is that we now have a specific cover to hang my hat on. We can work with this one specific cover, and try to show things about, and hopefully get a contradiction. Let's maybe drawn an example:

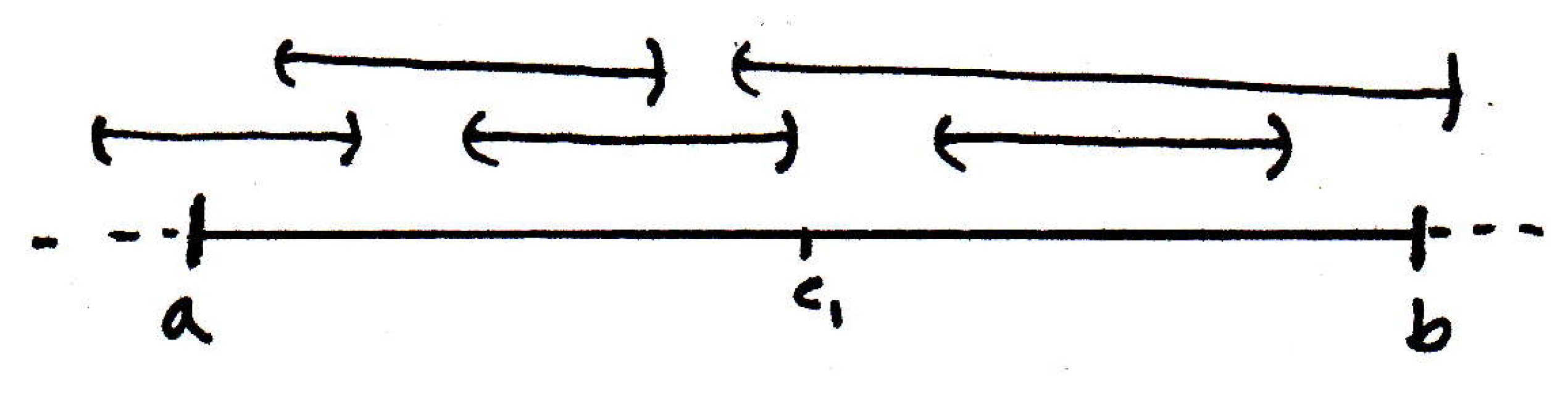

Maybe such a cover consists of sets that look a lot like the above, where we have a bunch of sets, possibly lots of them, but pretend for a second that that is our cover. Obviously an infinite cover that has no finite subcover that will cover . We're going to try to get a contradiction now, and we will use the nested interval theorem to help us get this contradiction. The idea is that if our cover has no finite subcover for , then would it not be true that for any subset of the subinterval of the real line that this is also true (i.e., the subset of the subinterval also does not have a finite subcover)? That is, if we divided the interval into half, maybe labeling the location of the bisection with , then our original cover covers both halves, and .

Why would it have to be the case that at least one of these intervals, or , also has no finite subcover of our original cover? If both halves had a finite subcover of our original cover, then you would just union those two collections, and then you would have a finite subcover of our original cover for the whole interval. Great I have another interval! So what's the next step. Let's write down what we have thus far.

We have that covers and , where at least one (maybe both) has no finite subcover. Which one? Who cares. Just say one of them. Let's call it . For the sake of specificity, suppose . What are we going to do next? Split it again! Let's split exactly in half to obtain two more intervals, and , and let's call the interval without a finite subcover (note that at least one of these intervals, maybe both, does not have a finite subcover, so we are justified again in this choice). Now what? Subdivide again!

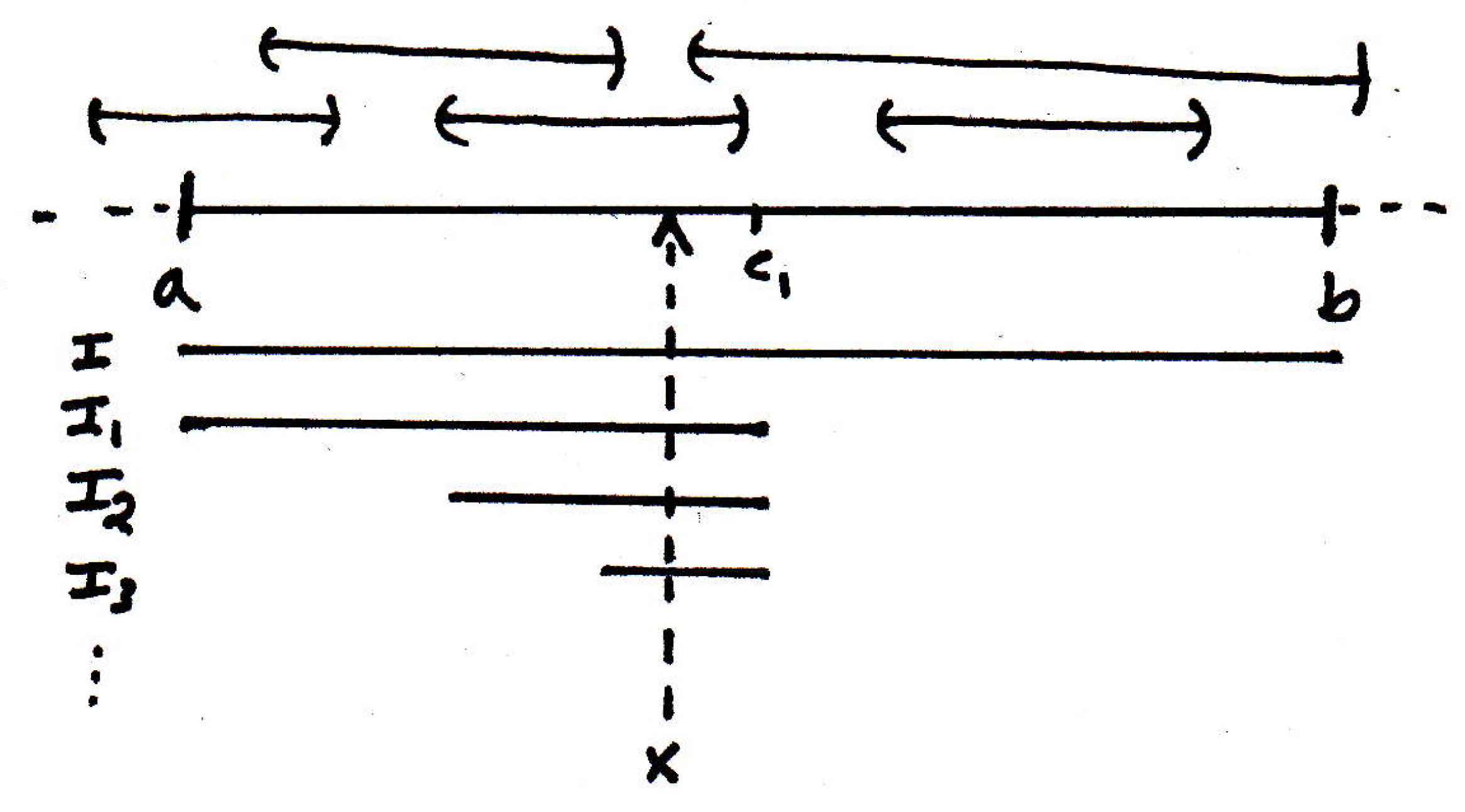

To recap, we started with the subinterval of the real line . We supposed were not compact with the hope of eventually obtaining a contradiction. If is not compact, then there must exist an open covering of without a finite subcover. We covered with an open covering and assumed there was no finite subcover. Then we split directly into half, where marked the point of splitting. Hence, we obtained two intervals, and , and we noted that at least one of these intervals (possibly both) could not have a finite subcover (otherwise we could union the finite subcovers for both intervals to obtain a finite subcover of which we are assuming does not exist). Without loss of generality, we let , where we are simply choosing to denote one of the subintervals of that does not have a finite subcover of . We then bisected into two intervals, and , noting again that at least one of these intervals (possibly both) does not have a finite subcover. We let denote the interval without a finite subcover without loss of generality. And we continue this process, noting that

which is a sequence of nested closed intervals. What else is true of this nested set of closed intervals? None of the sets is covered by any finite subcollection of ; that is, no interval has a finite subcover. Not only do none of them have a finite subcover but also they've been chosen in such a way so that they are getting smaller and smaller. They're always decreasing by half each time. So we have this nested sequence of closed intervals, each halved at each step, and with no finite subcover of . Let's actually set these important properties apart for ease of reference:

and

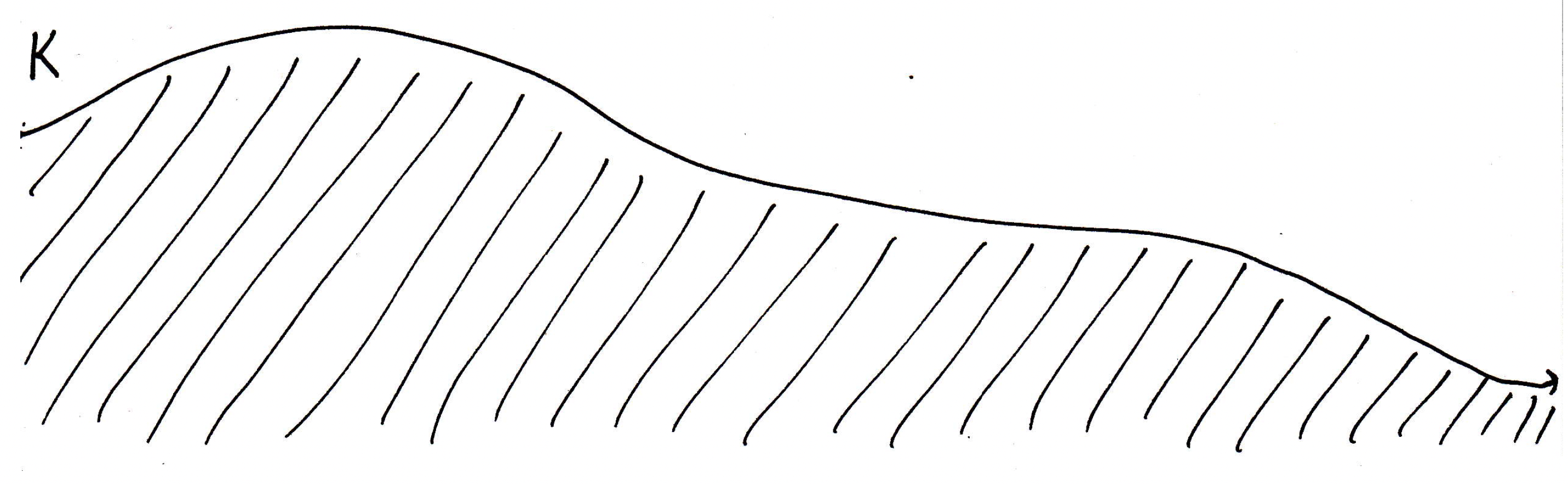

How might we be able to use the nested interval theorem here? Well, this theorem tells us that there exists a point for all . Let's draw a picture:

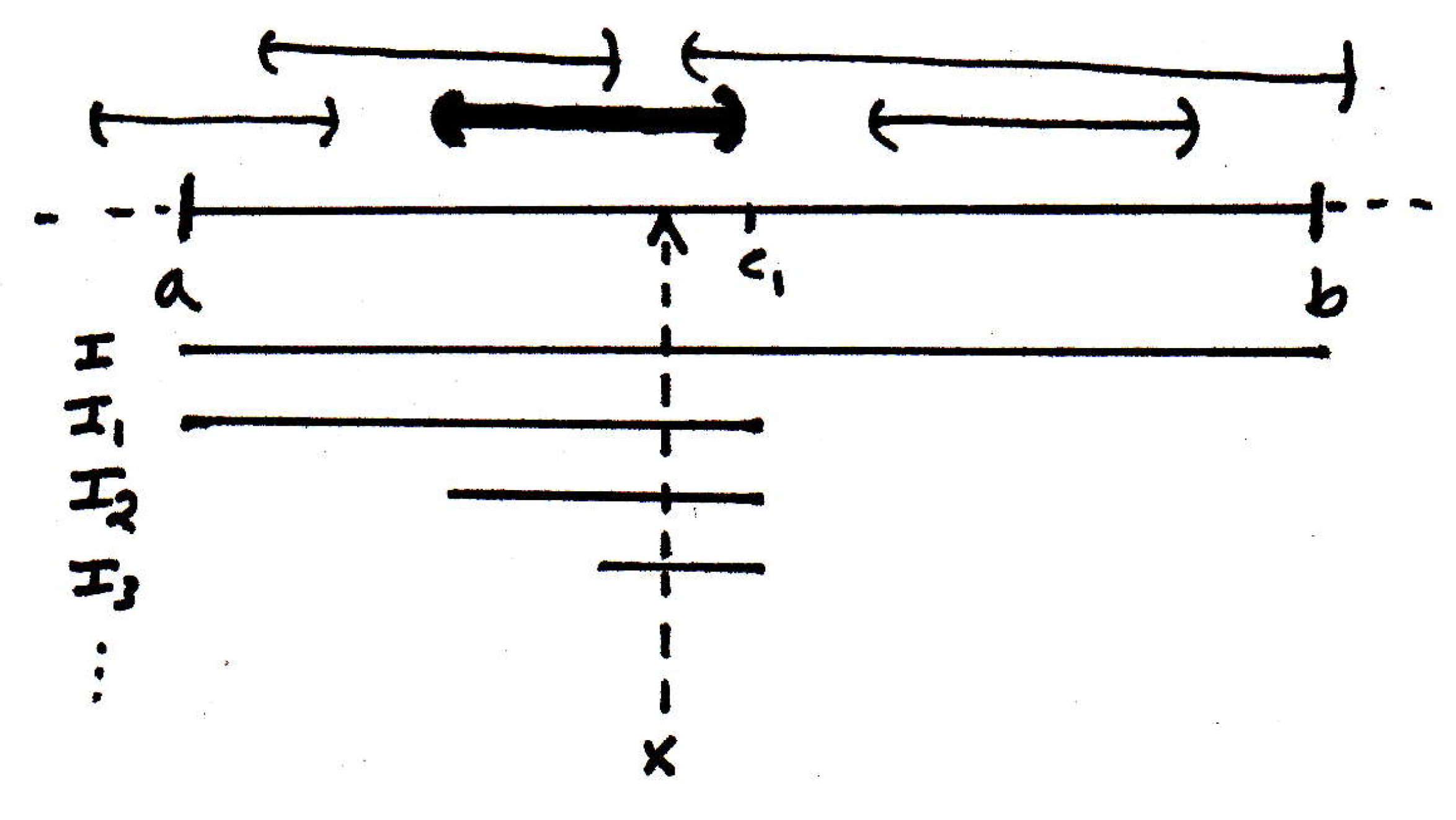

In the above, we had our first interval that we started to bisect into the nested closed intervals , , , etc., where each time you're picking one of the two halves at every step. The nested interval theorem tells us that there exists a point in all the sets , , , , \ldots, where we've chosen to denote this point here, and maybe it lives roughly where the arrow is drawn. Do we have a contradiction yet? Not yet. So what! I have a point that's in all the sets. So what? The single point is somewhere on the interval where is in some open set of the cover . Maybe it's in the open set that's now very bolded below:

Of course, there may be many open sets overlapping, where is in all of those open sets, but the above is just our example where clearly lives in the bolded open set. Let's call the particularly bold open set in the picture above ; that is, . So then what? Where will our contradiction come from? Well, is in some open set of the cover , where we've denoted this particular open set of as . Why is that going to contradict anything about our nested interval construction?

Since , where is an open set, then this means is an interior point of . Therefore, there is, in fact, a neighborhood of that's still contained in ; that is, in , which is the case we are dealing with here, this means that there is an interval around that's still within the open interval represented by . (Recall that neighborhoods and open sets are represented by open intervals in , which is what we are dealing with in this example.) Thus, there exists some such that . Let's try to represent this with a picture:

So we have this neighborhood , which is denoted by the open interval that looks like in the picture above. It's clear in the picture above. (Recall that is represented by the open interval that looks like in the picture above while is represented by the very bold open interval in the picture above). So why does this contradict anything about our construction? Well the problem is that , not only a finite subcover of but just a single element of , will cover one of the intervals . Which one? Will cover ? No. ? No. Because I'm halving the intervals at every stage, the intervals will eventually get so small that they'll live inside and therefore inside . That's our contradiction. So by the first equation above, some is completely contained in (i.e., we have for some ), meaning covers , which contradicts the second equation above, thus concluding the proof.

-

Question about above proof: What would fail in the above proof if we were not looking at but ? We know is not compact, but what would go wrong in our argument if we tried to prove it was compact? Well, the closed interval is just like the open interval except the endpoints, so what could happen? The intersection of the sets could be one of the endpoints, and that's the case where you'll have problems with the argument given above.

-

Tangential question: Why do we always consider open covers? Would it ever be of use to consider using closed covers? You can develop the whole theory of compactness using just closed sets, but then instead of unions that cover you'll be talking about intersections that are finite. The question may be deeper such as why open covers at all? This may be partially addressed when dealing with Cantor's intersection theorem which we'll discuss in a bit.

Using compactness to establish meaningful results

How can we use the fact that is compact to help in establishing other meaningful results?

-

Introduction: It was surprisingly nontrivial to show that the creature was compact, but it's going to give us a lot of other things as a relatively easy consequence.

-

The Heine-Borel Theorem: The set in is compact if and only if is closed and bounded. This basically characterizes which sets in (or in ) are compact. We have two directions to prove here, and let's start with the forward direction first.

-

Forward direction (proof): We have already shown that if is compact, then is closed. We have also showed that if is compact, then is bounded. Thus, we have shown that if is compact, then is both closed and bounded. Thus, there really is nothing to do here. (This direction is true for arbitrary metric spaces.)

-

Backward direction (proof): It should first be noted here that this backward direction is not true in arbitrary metric spaces. (It would be informative to try to come up with some examples to illustrate this.) The goal here is to show that if is closed and bounded, then is compact. What can we do? Well, if is bounded, then for some . (If is bounded, then certainly lives in some interval sufficiently big enough, perhaps from to for some . And if lives in , then must also live in . That's what it means for to be bounded.) So we have that for some as a consequence of being bounded. Well, what's true of ? It's a closed interval that is thus compact due to our previously established result. Note that at the outset we assumed was closed. Since , we know that is a closed subset of a compact set, and thus is compact. This concludes the proof.

-

Appreciation: Note how easy this was after we established that any closed interval is compact. We did a lot of hard work in establishing that, and now we are simply reaping the benefits. So any subset of that is closed and bounded is compact. Now, what would change for the proof given above if we were working in ? We would just have to show that a -cell is compact (the set is really a "1-cell" \ldots so just replace the interval with a -cell and you're good to go), but this was already pseudoestablished previously when we showed that all sets of the form are compact. The proof that -cells are compact may be found in [17]. Now, where does the proof of the backward directon of the Heine-Borel theorem fail if we are not using the standard metric? Our argument rested on the fact that any set of the form is compact. So let's look at the interval using the discrete metric. It says distance is 0 if they're the same point and 1 if they're not. Is that compact for an infinite set (in fact an uncountably infinite set)? No, it's not compact! Why? Because you could cover every point with a ball of radius . That's an open cover, where every point is precisely one element of the cover. So you can't remove any of them and still be a cover. So under the discrete metric, is not compact. So where would the proof of the fact that is compact break down using the discrete metric? Well, the proof that was compact used the nested interval theorem.

In our proof that was compact, we assumed it wasn't. So we were assuming there existed an open cover of that did not have a finite subcover. And we talked about bisecting each interval, beginning with . So each half had no finite subcover. For the point that we came up with, what did it mean for to be in some set of the open cover? (Recall in our proof we had that .) Well, is interior, but the interior of such a point is not actually an interval when using the discrete metric (we had an interval in our original proof only because we were using the usual metric). So the point is an interior point, but the only thing in that interior set is the single point itself. Thus, you'd never be able to have a contradiction that the cover necessarily covers one of the sets which is where the contradiction came from in our original proof.

-

Examples when the reverse implication fails: When might the reverse implication for the Heine-Borel theorem, namely that if is closed and bounded then is compact, fail? So what might be a metric space where a set is closed and bounded but not compact? Well, a discrete metric on an infinite set would work, as discussed above in the "appreciation" note. To flesh this out more, consider the discrete metric on an infinite set . Well, then is closed. Why? It contains all of its limit points, which namely are what? Nothing! There are no limit points when using the discrete metric because everything can be separated by these isolated balls. So is definitely closed. Is bounded? If all distances between points that are different is 1, then is bounded? Yes! Everything's in a ball of radius 2 around any other points. But is compact? No, because you can't remove any element of the cover if the cover consists of balls of radius .

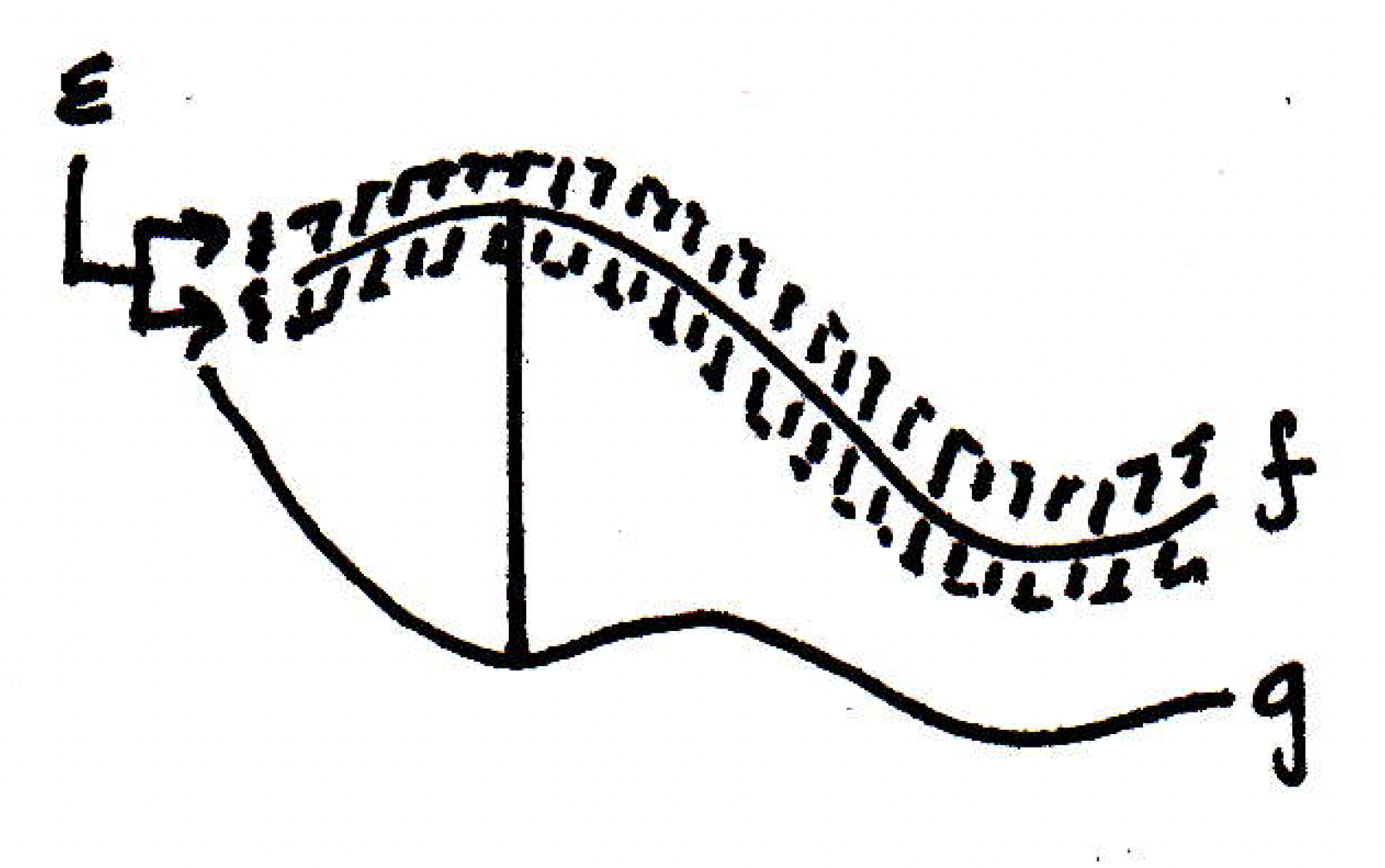

Let's try a related example that's not necessarily or . Going back to your calculus knowledge, you might recall what it means for a function to be continuous (this will all be looked at more thoroughly soon, but this is nice for a little start). You could let be the set of all continuous bounded functions , where may be read as "the continuous functions bounded on ." Let's let the metric between any two points just be the supremum metric: . So the metric basically refers to the maximum distance between functions and :

In the picture above, the long vertical bar is represents the maximum distance between and . So here's a question: What's the neighborhood around a particular function going to look like? Give me an -ball around . What does an -ball around going to look like? In the picture above, we have a sort of "ribbon" around that is dashed, and the distance between the dashes above and below are a distance away from . So, to be in an -neighborhood around is any other continuous function that lives within the "ribbon." So we could talk about covers of sets. An open set of functions is basically a set of functions such that for any function in that set you can perturb it a little bit and it's still in that set; perturb it within a ribbon. So function spaces are infinite-dimensional spaces, and you can certainly construct examples that are closed and bounded but not compact. So let's construct one.

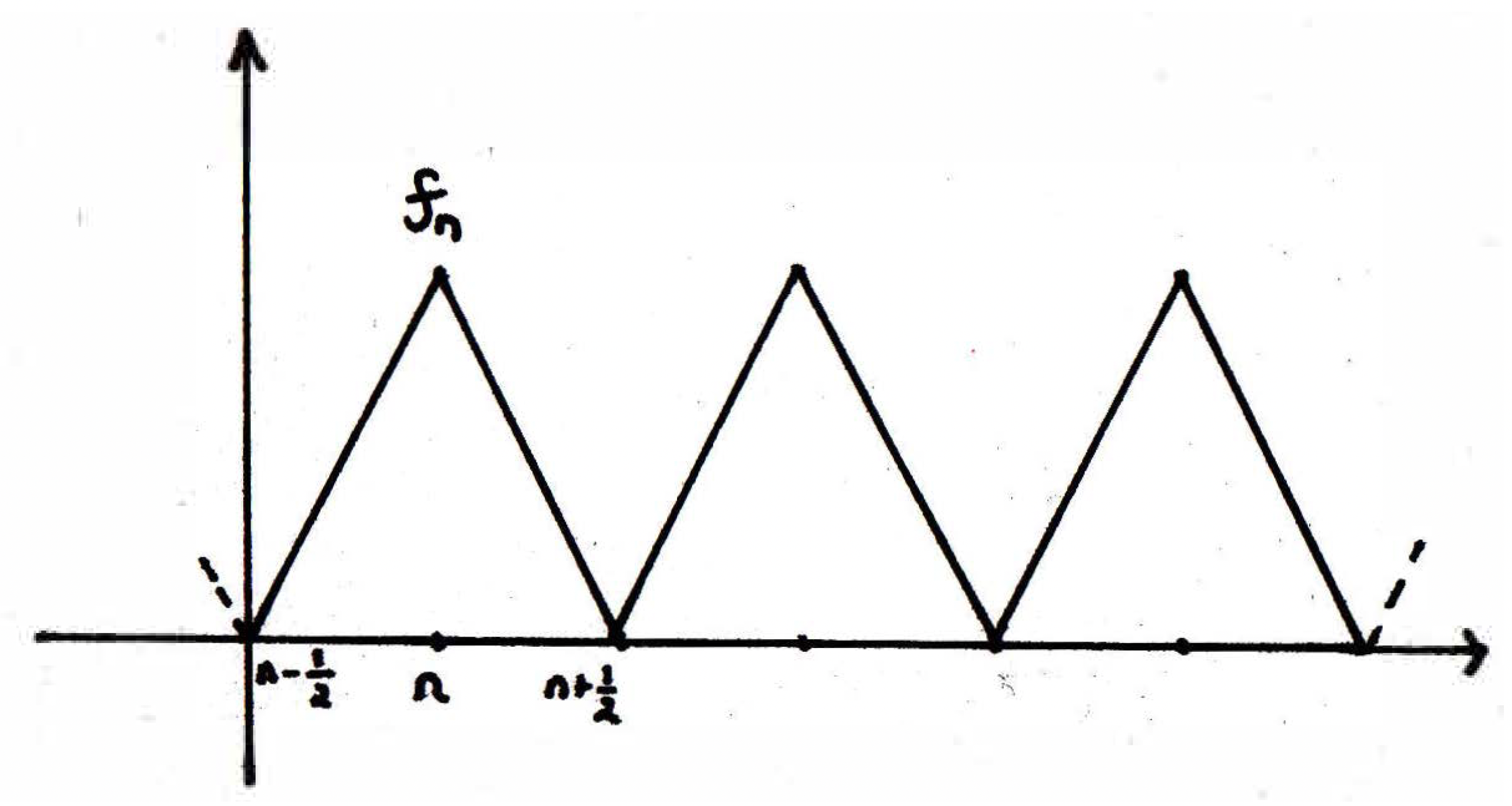

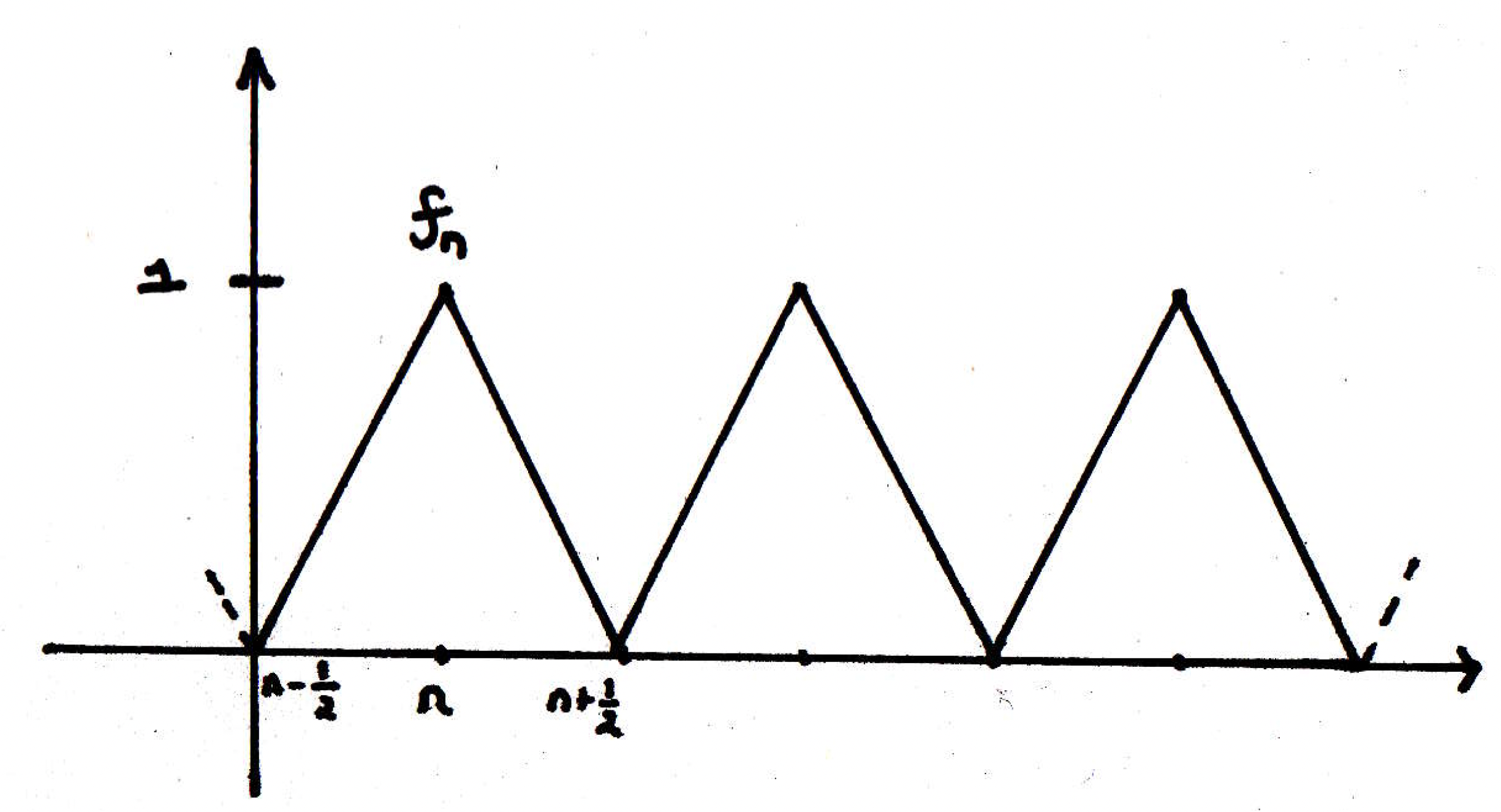

Let's take a function that has a spike at the point , and let's call this function , and let's further say that we will limit ourselves so that is only nonzero between and . If we look at all such functions, then we will end up with a picture that looks as follows:

Let's call the set of all such functions ; that is, . We claim that is closed. Why? Take a little ribbon around this set, around one of these functions. If we take a ribbon around one of these functions of size something small, say less than . Would you agree that none of the other functions live inside such a ribbon? So has no limit points and hence is closed. It's infinite also, yes. Is it bounded? Well, what's the distance between any two functions? At most 1 if we modify our picture as follows:

So, when dealing with the supremum metric, the set is bounded (the distance between any two functions given the construction in the picture is at most 1), the set is closed (it contains no limit points). In fact, the topology induced by the supremum metric on the set looks just like the discrete metric doesn't it? So now the question is whether or not the set is compact. If you wanted to cover with an open cover that has no finite subcover, then take little ribbons. That's an open cover of but with no finite subcover.

Other characterizations of compactness

What are other characterizations of compactness that might prove useful?

-

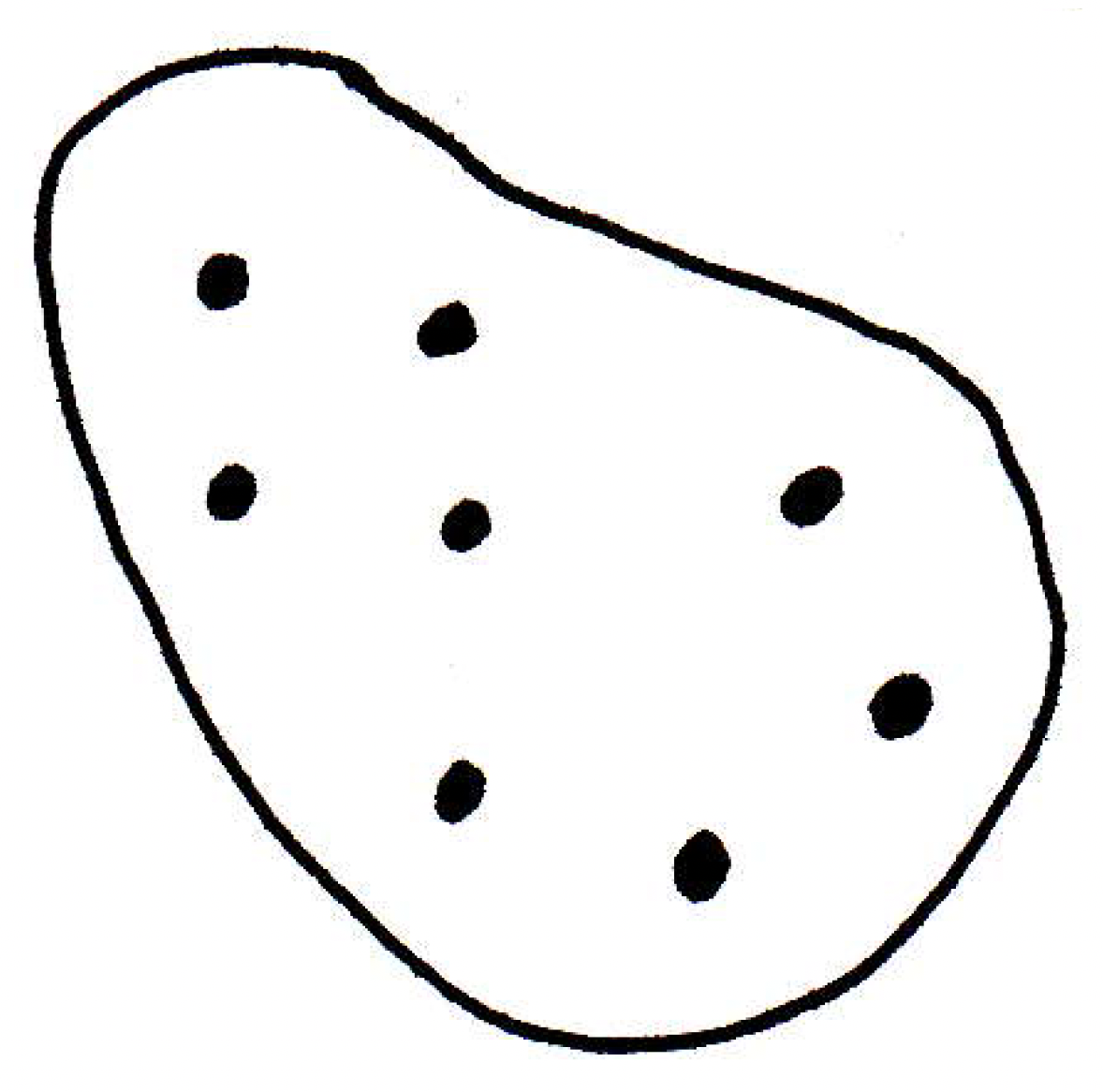

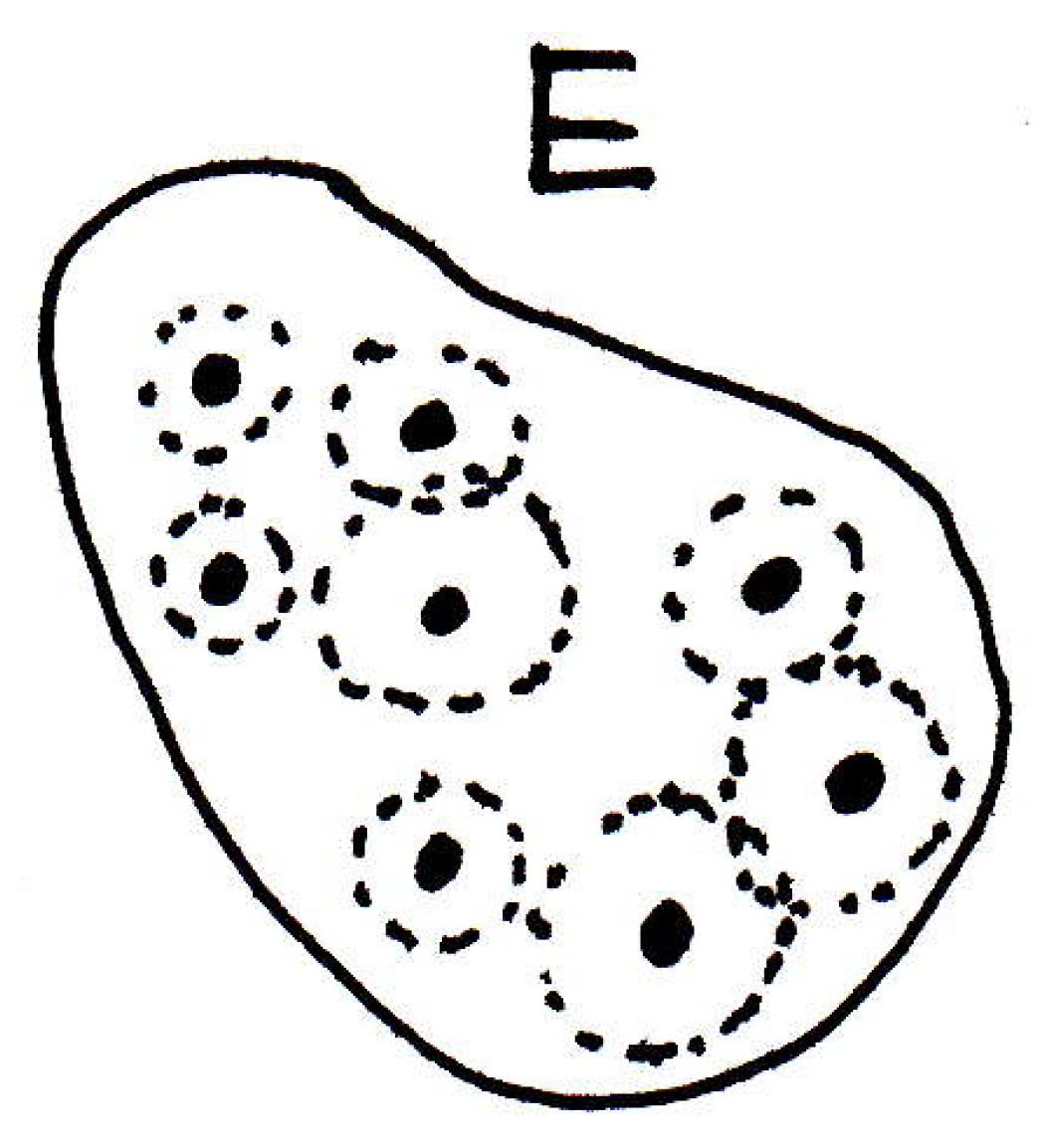

Compactness and limit points: In an arbitrary metric space, the set is compact if and only if every infinite subset of has a limit point in . (In the pictures given below, we note that is the whole set while is an infinite subset of this set.) If you think of compactness as a small set, does this characterization make sense? That is, if you have an infinite subset of , and it's small enough, then all those points should do what? Here's kind of a small set:

If you have infinitely many points, then what should be true? If you try to pack a large number of points in a small space, the points should what? They should accumulate somewhere! They should have a limit point. That's sort of the intuition. That's basically the idea. Now let's see if we can prove this. Let's do the forward direction first.

-

Forward direction (proof): What would go wrong if there was an infinite subset that had no limit point? What would go wrong with the fact that it's compact? Let's draw another picture:

So now we have an infinite subset that has no limit point. What does that mean about each of the particular points in the picture above? Well, that means that each point is spaced out in some way. Why? What does that have to do with being or not being a limit point? If each point is not a limit point, then we could end up with a picture like the following:

That is, we could find a ball around each point that would not contain any other point. The balls might overlap but they would not contain the other points. So, if no point of is a limit point of , then each point has a neighborhood containing no other point of but . But then covers with no finite subcover.

Note that this proof works because the set is closed. It does not have a limit point in , and it cannot have a limit point of because then that limit point would also be a limit point of , and therefore a part of (since is closed). Therefore, has no limit points, and therefore contains all its limit points and is therefore a closed subset of (which we have prove means it's compact.)

-

Reverse direction (proof): This direction assumes that every infinite subset has a limit point in the set . This direction is actually a lot harder to show for arbitrary metric spaces, and the proof for arbitrary metric spaces is a hard homework exercise, which may be assigned with hints, but the proof that follows is for even though it's true more generally. It's just easier to get a sense of why it's true in .

What theorem might be helpful here if we're showing something is compact in ? The Heine-Borel theorem may help! We'll show is closed and bounded. Suppose is not bounded. Why would that contradict the fact that every infinite subset has a limit point? The set goes off forever. Below is some set :

The set is not bounded, and we are trying to construct this proof by contradiction. We're assuming that every infinite subset has a limit point. Why is it the case that if were not bounded then we would contradict the statement that every infinite subset has a limit point? Can you think of an infinite subset that would not necessarily have a limit point in the picture above where goes on forever (see the picture above again). Can you think of such a subset? Does the picture suggest one? How about some set that just keeps going off forever? How can we make this precise? Consider the following picture:

Is it not true that the set of points illustrated above is an infinite subset of that has no limit point? Why does it have no limit point the way it is drawn? Because we can surround each point by balls that cover only exactly one point. So this is the idea. How can we say this? Well, if is not bounded, then choose a sequence such that . Since we are working in , we could make the distance from the origin be bigger than :

In the picture above, the numbers at the top of each vertical line denote the distance to the origin from the base point of each line (i.e., , , etc.). Well, what if the point we picked slightly beyond distance 4 is actually close to the point partway between distance 5 and 6? Or maybe other points are closer to other ones further down the line. Why is that not a problem with what the picture is communicating? This infinite subset will not have a limit point because if it did, then that point would have to be somewhere, maybe even between the millionth and millionth and oneth radius, but what did we show? Why can't that be a limit point? Because in the neighborhood of a limit point, you must have infinitely many points, and you only have finitely many points that are to the left of a million and one. That's the argument.

So our infinite subset of set does not have a limit point because the neighborhood of a limit point must have infinitely many points of the set, but any point in the picture has only finitely many points that could be near it. So is bounded. Now we want to show that is closed.

Suppose is not closed. How could we obtain a contradiction in this situation? So we'd have a picture like the following where is not closed:

Take a limit point that's not in , but then any neighborhood around has a point of in it. So pick one:

And now what? How do I get like a whole bunch of points that accumulate on ? Keep taking smaller and smaller radii where the radii go to 0, and pick points inside each time:

So if is not closed, then there exists that is a limit point of . Now choose such that , where the set has a limit point at . And what's the other thing you'd have to show? Not only does have a limit point at but we're trying to show that has no limit point in . Why does have no limit point in ? Is it possible for to have a limit point that's but also something else? Hopefully note. Why is that the case? With the points of constructed as they are (each one within another nested ball where they are accumulating towards ), why can only have one limit point? Well, if had two limit points, then those limit points would have some distance between them, and then it cannot be the case that the sequence is getting closer to one limit point and the other at the same time because, eventually, the triangle inequality would fail. That's the idea.

-

An important corollary (Bolzano-Weierstrass): The fact that is compact if and only if every infinite subset of has a limit point in has a simple corollary, which is sometimes known as the Bolzano-Weierstrass theorem: Every bounded infinite subset of has a limit point. Why is this a corollary? Is compact? No. So is not compact, but what? You give me a bounded subset that lives in a compact -cell. The boundedness gives you what you need. So, if a subset is bounded, then is in some compact -cell, and therefore what? The set is an infinite subset of a compact set and therefore has a limit point in the -cell.

-

Another characterization of compactness (finite intersection property): Suppose you have a bunch of sets , and they are compact subsets of some arbitrary metric space . We say a collection of sets has the finite intersection property if every finite subcollection of has a nonempty intersection. Our goal here will be to prove a consequence of the finite intersection property, namely that if every finite subcollection of has a nonempty intersection, then is nonempty; that is, .

You should think of this theorem as a generalization of what theorem that you have seen before? The nested interval theorem! Closed intervals are compact. Isn't it true for nested intervals that if you take any collection of finitely many of them that their intersection is clearly nonempty (because it's the smallest one)? The conclusion there was that there is a point in all of the nested intervals, and that's the conclusion here. So this theorem generalizes the nested interval theorem and is true for arbitrary metric spaces, not just -cells in . Okay let's see what the proof is, and it's not too bad.

Our statement to prove is about compact sets, and compact sets are closed. So their complements are open. So this statement is really about open sets. Let , and these sets are open. Now, if we had , then the complements should cover everything because if a point is in the intersection, then that means the point is not in any of the complements. So if there's no point in any intersection, then every point must be in some complement, which is in one of . So here's the key insight: Fix one in . Pick your favorite one. If we had , then cover that one particular set , where we know is compact. But then what does that mean? It means there exists a finite subcover that covers . What does that mean? It means if covers , then 's intersection with their complements must be empty; that is, we must have , which concludes the proof.

Note that this was a proof by contraposition. The statement to prove was as follows:

- If every finite subcollection of has a nonempty intersection, then is nonempty; that is, .

What we have shown is the following statement:

- If is empty, then there exists a finite subcollection of has an empty intersection.

So, we started by assuming , and we concluded that the finite subcollection of , thus concluding the proof by contraposition.

So what we have here is another way of thinking about compactness in terms of a finite intersection property instead of a union of open sets which cover a compact set. Here we basically have a bunch of compact sets which have the finite intersection property so their entire intersection must be nonempty. A classic example of this is a set called the Cantor set.