14 - Connected sets and Cantor sets

Where we left off last time

Let's recall some of the results and ideas from last time before discussing the Cantor set and connected sets.

-

Theorem due to Cantor: Let be a collection of compact subsets of some metric space . If every finite subcollection of has nonempty intersection, then the set is said to have the finite intersection property or FIP; that is, if , then we say that has FIP.

-

Corollary to Cantor's theorem: Suppose we have a sequence of compact sets that are nested. Then is nonempty. This was the generalization of the nested interval theorem.

-

Characterization of compact metric spaces or compact spaces using closed sets: The usual definition of compactness involves open covers, but there is a characterization of compact sets that you could take to be the definition, if you wanted, that talks about compactness and closed sets. That's the following characterization which is a theorem:

Theorem. The space is compact if and only if every collection of closed sets satisfies the finite intersection property (here the finite intersection property is saying that if every finite subcollection has nonempty intersection, then .).

What does this mean? If we have a collection of closed sets that has the finite intersection property, and if that's true for any collection, then is compact and vice-versa. Let's see why this is true.

-

Forward direction (proof): This direction is pretty trivial based on what we've shown already. Why is that? Well, what are we going to choose to be our compact subsets of a metric space? We're going to assume that itself is compact, and maybe we'd like to use Cantor's theorem. So you give me a collection of closed sets, and I want to show that it satisfies the finite intersection property. Then what sets will we use in Cantor's theorem if we want to apply that theorem?

Given closed sets , these are closed subsets of a compact set so they are compact. So apply previous theorem.

-

Backward direction (proof): Here we want to show that any collection of closed sets that satisfies the finite intersection property implies that is compact. Let's just talk about how the proof might go. I want to show that every cover of has a finite subcover. So, given an open cover, can we use our assumption(s) effectively? So given an open cover, are there any natural closed sets to look at? Look at the complements! The complements are a bunch of closed sets.

Another proof strategy would be proof by contraposition, where we would assume that was not compact and try to show that there exists a collection of closed sets that did not satisfy the finite intersection property. How might this proof start? Well, by assumption, is not compact. Thus, there must exist an open cover with no finite subcover. We could start with that. What would that mean? Look at the complements which are closed, and if we have a cover, then the complements should basically have an empty intersection.

What you see through all of this is that there is a way to deal with compactness just using closed sets.

-

Lack of characterization of compactness using closed covers: There isn't a closed cover characterization of compactness, and that should make sense to us why? Well, points are closed in metric spaces. So, if you were to demand a space to have the property that every closed cover has a finite subcover, then you'd really just be demanding that the space is finite, which is a bit too strong of a condition. It's just saying something that you already want. Then if you say well let's just rule out points, saying you don't allow those in our closed cover characterization of compactness, then what are you doing? You're really taking a point and allowing a little interior ball around it, so you might as well use open covers. So you can't really expect to have a closed cover characterization, but there is a finite intersection property characterization of compactness that uses closed sets.

The Cantor set and its properties

What is the Cantor set and what are some of its properties?

-

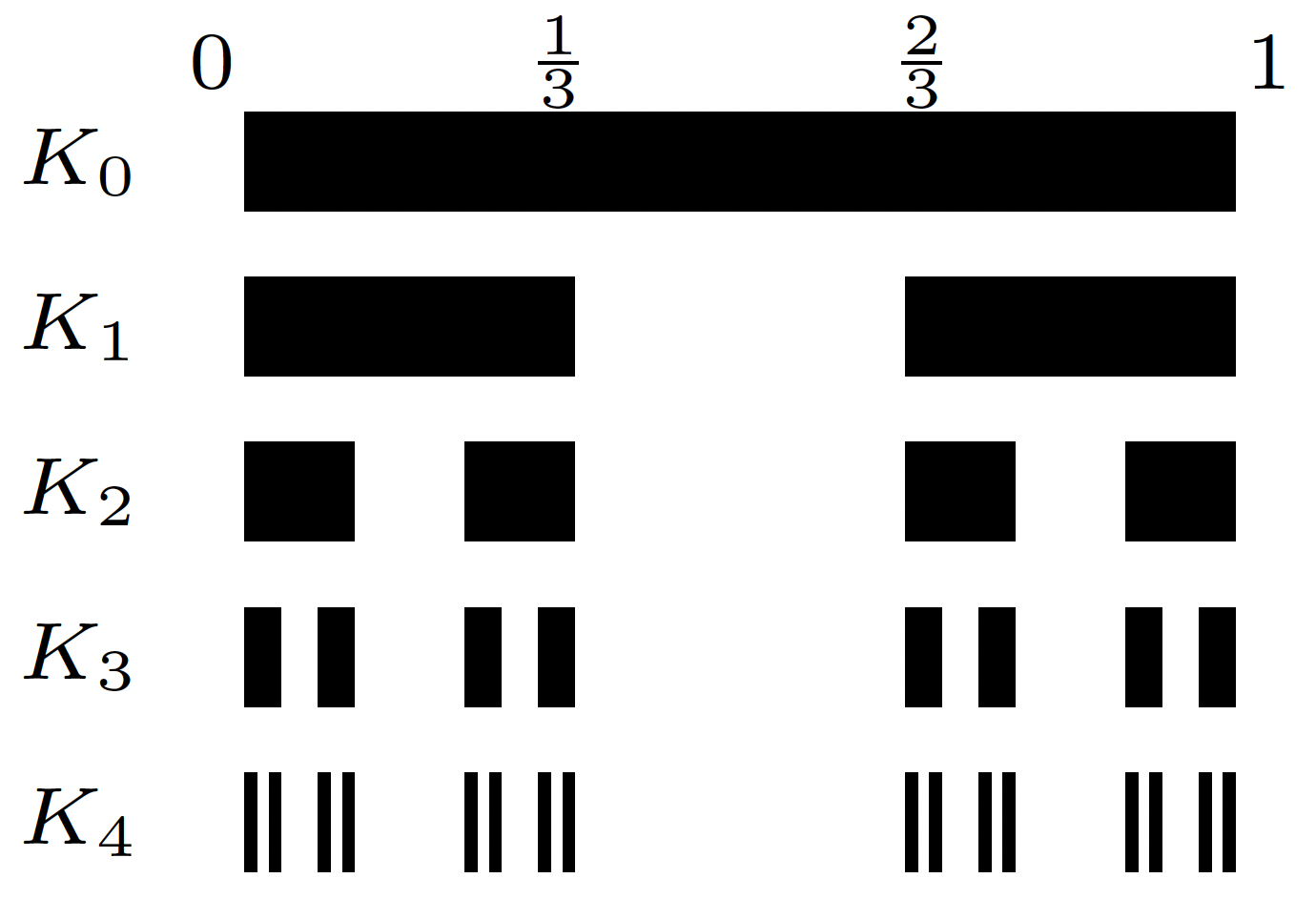

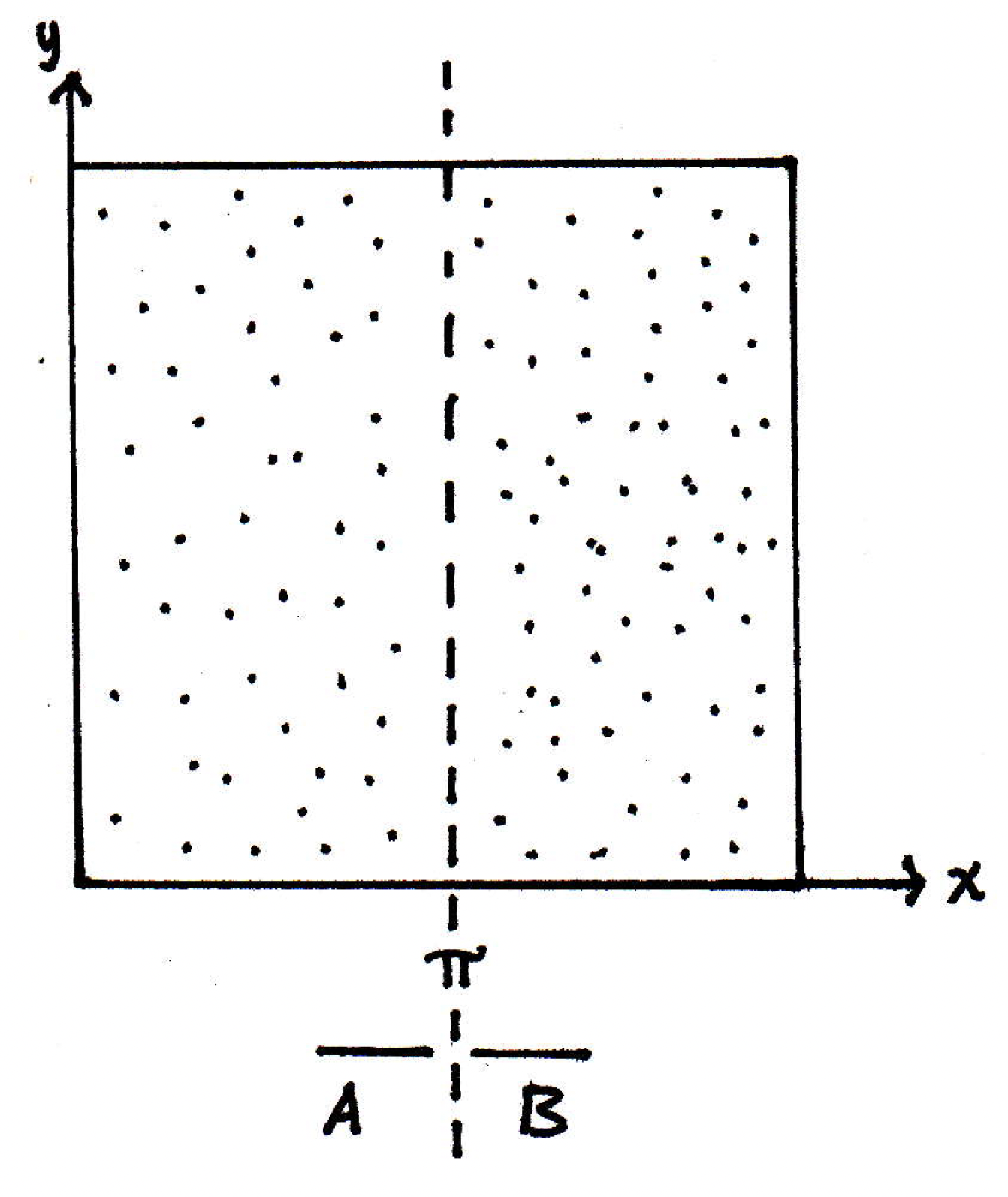

Constructing the Cantor set: Start with the interval . Now construct by removing the middle third of ; that is, . Now remove the middle thirds of each interval again to make

And continue on in this way to get a set that looks roughly as follows through :

What can we say about each of the sets above? How many intervals does have? It has intervals, but finitely many in any case. Are these intervals or sets closed? Yes, they are the finite union of intervals that are closed. Are these sets compact. Yes, because they are closed subsets of a compact set which we know the interval to be. So are closed, compact, and what else? They're not open because if you take a point at the endpoint, then it's not an interior point. But what are the sets in relation to each other? Nested! So their intersection is nonempty! Can you see some points that must be in every set? How about 0, 1, , , etc. So endpoints of intervals are definitely still in each .

We will denote the cantor set as . This construction was made over 100 years ago, but with the advent of computers and computation, such sets actually pop up in very natural ways. The set has a very fractal-like structure. If you've ever seen pictures of so-called strange attractors in physics, they look very much like Cantor sets. Of trajectories. So what's so special about the set ? Here's a question: how many points are in such a set? There are infinitely many. We can see that fairly clearly. Are the points of only endpoints or are there any other points? Let's find out.

What else can we say about ? Are there any intervals in it? No? Are there any interior points? Why not? If had an interior point, then what would go wrong? Well, eventually any such interval gets cut, so doesn't have any interior points. If you think there are only endpoints of intervals that make up , then how many points are there? It's infinite sure. Countably many actually because it's the countable union of a finite number of endpoints for intervals. Here's a summary of some of the things we've just noted:

-

Closure: The set is closed. Why? Because is the intersection of closed sets.

-

Perfect: The set is perfect, which means is closed, and every point of is a limit point of . What does that mean? No point is isolated. Can we think of any other perfect sets besides ? How about the closed interval? All of is a perfect set. There are lots of perfect sets, but is a special perfect set because it's perfect and it has no interior. We haven't justified that each point of is a limit point, but we claim that this fact follows from the following insight.

-

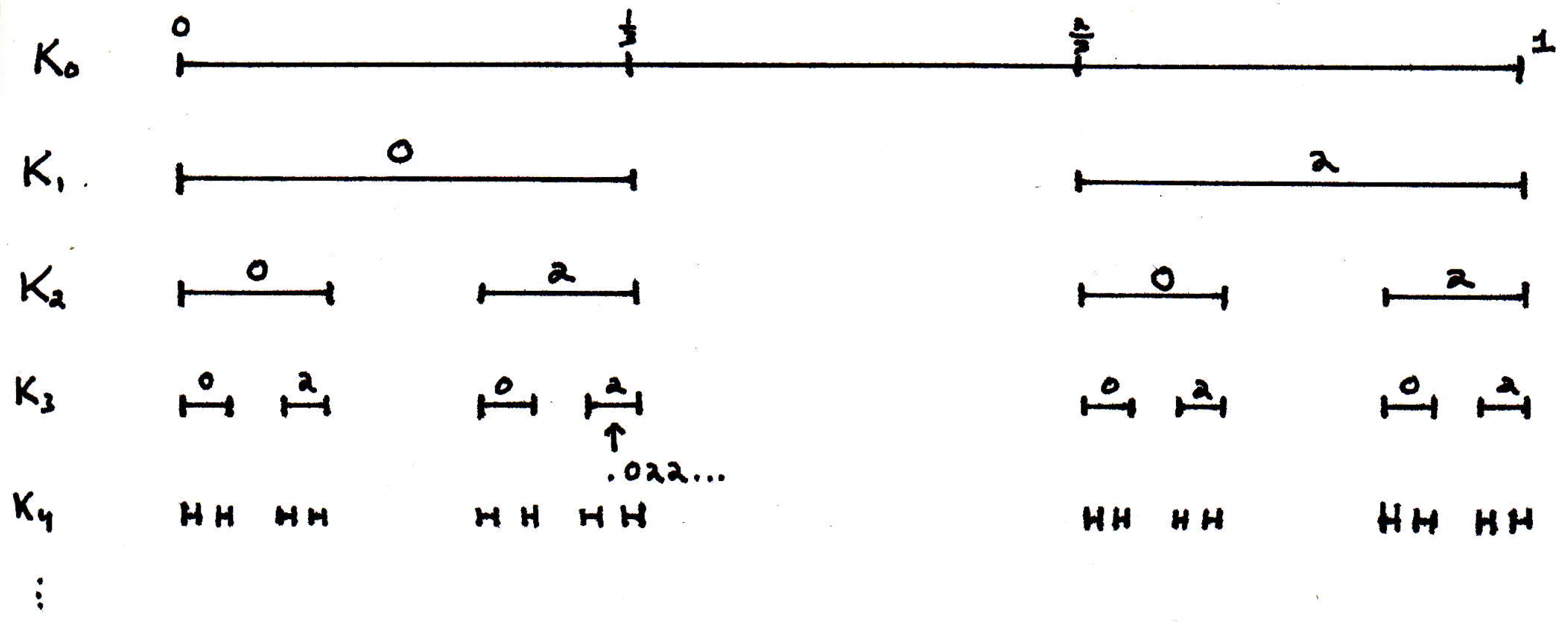

Ternary expansion: The set consists of real numbers that have a certain property. When you write the real number in ternary, then its ternary expansion will only have 0's or 2's in its expansion. What does this mean? When we write a number in ternary, instead of using powers of 10, we will use powers of 3. So in ternary, we use three digits, namely 0, 1, and 2. It's probably quite clear that all of the numbers in the interval begin with 0 (we'll get to itself in a moment). In other words, each number in the first third interval of is of the form

For the middle third of , we'd have each number in this interval of the form

and finally for the last third of , we'd have each number in this interval of the form

We could continue this pattern, and if we wanted a point in, say, the fourth interval of , namely some number in the interval , then we claim that all of the numbers in the interval begin with the ternary expansion . Here's a picture:

So ternary looks something like , where each number is written as a power of 3. So we would have numbers like

For decimals, we're just considering everything to the right of , of course. Now, what about ?

-

Example 1: We claim can be written in ternary using only 0's and 1's. How? We would have

an analogous situation to how for decimal expansions. So the representation for is not unique because it could also be written . Now, the only ones in decimal that are not unique are the ones that end in all 0s or all 9s because one could be turned into the other. The only ones in ternary that are not unique are the ones that end in all 0s or all 2s because one could similarly be turned into the other.

-

Example 2: How many points are in the Cantor set? Uncountably many! Why? It's exactly the same argument as Cantor's diagonalization argument. What this shows us is that not only is every point of a limit point but that is uncountable. It also shows that has non endpoints of endpoints.

-

Example 3: What's a point in that is not an endpoint? How about, say, ? This is not an endpoint is it? What are the only endpoints? The endpoints are the numbers in ternary that end in either all 0 all 2's. So is certainly never an endpoint.

-

Example 4: Are there any interior points of ? No. What would it mean to be an interior point? Well, if there were an interval around such a point, then some of those points would have to have 1's in their ternary expansion.

-

Example 5: Is every point of a limit point? Yes. Why? Is it not the case that for any number that you give me I can write it as a limit of a bunch of numbers that have only 0's or 2's in their expansion? For instance, the number is the limit of

Yes, every point is a limit point. What if our limit point has a finite ternary expansion? So how about 0.02? We could write 0.02 as the limit of

So why do we include the endpoints for the intervals in our construction? We'd have a much harder time showing lots of things. So, for instance,

-

Example 6: Cantor sets are totally disconnected, but now we have to define what it means for a set to be connected. But the basic idea is that if you give me two points, then I can find a disconnection that will separate those two points.

- Example 7: How long is the Cantor set? What do we mean by that? What does it mean to define the length of a set for sets that are really strange like ? One way you could define the length of a set is to ask what the lengths are of possible intervals that cover the set. And then take the infimum of the sums of those lengths. We've already shown that closed intervals \ldots you can only have countably many disjoint intervals \ldots so you can talk about the sums of the lengths of closed intervals that cover a set. That has a certain length. Then do so for all such closed intervals that cover a particular set and take their infimum. Then you could use that to define the notion of length for a crazy set like . What's interesting for this Cantor set is that it has length 0. We say has measure 0. Basically, for any , the set can be covered by intervals of total length less than . So we have uncountably many points but length 0!

-

-

-

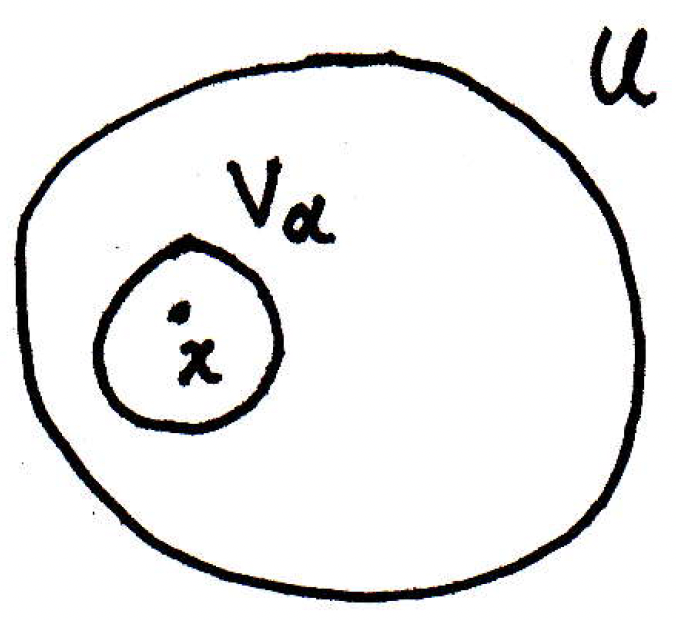

Homework note: This note concerns problem 26 in [17], where this problem introduces a concept. This problem talks about a base for a metric space. So let's try to get some intuition as to why we care about a base. Actually, the term "base" is more particular to Rudin; nowadays, the term "basis" is more common than "base." What is a basis for a vector space? There are many ways to describe it, but the operative concept is that a basis is what you build other things from. So you can build any vector as a combination of basis vectors. Well, this is analogously the same concept here. What is a base or basis for the open sets of a metric space (or a topology in topology)? If you give me any open set and any point , then a base is some collection , where we don't really care which collection it is, but it has the following property: You give me any open and any point , then what's true about a basis is that there's a point of the basis that surrounds that's inside of . Consider the following picture to make this clearer:

Saying the above more precisely, for every , there exists such that . What's the big deal here? The big deal here is that I can do this for every point in . So can be written as the union of a bunch of basis elements just by taking the union for every point . So every open set is the union of base elements. This problem in Rudin asks you to explore this concept. The reason is really that there are all these concepts that have to do with the size of a set. So if you have a metric space where the base is countable, then it's small in some sense. If you have a metric space that has a countable dense subset (i.e., separable), then it's small in some sense. And it turns out that if you have a metric space that is compact, then it has a countable base. A compact metric space has a countable dense subset. So these notions of smallness somehow coincide, and you're given other tools for showing that a space is not compact. If you know that a compact metric space has a countable base, and you find a metric space that doesn't, then it can't be compact. Other strategies for showing not compactness!

So the idea of a basis is basically you can build up all open sets from just 's. One basis for a metric space is just to look at balls. That's a basis. We've already seen that. But you could also take other things to be basis elements. So that's a word about bases.

Connected sets

What are connected sets and what is their utility?

-

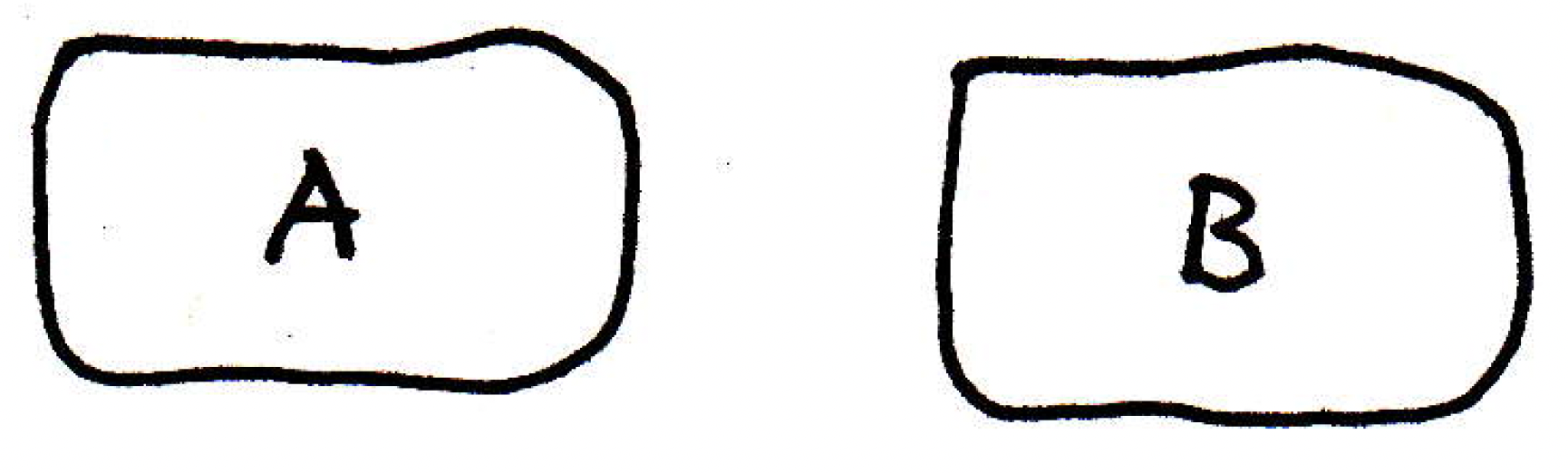

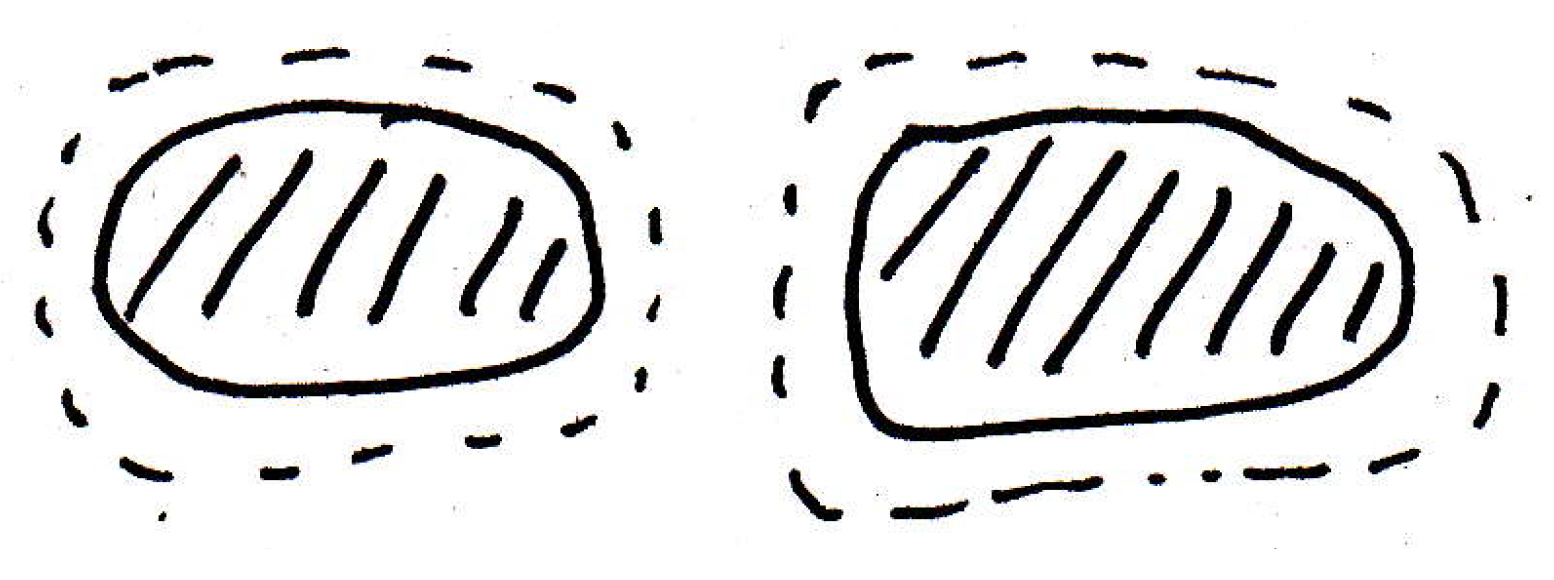

Motivation: What does it mean for a set to be connected? Intuitively, does the set

appear to be connected? Sure. But does the set

also appear to be connected? Probably not. But how do we make that feeling or notion precise? It turns out it's a lot easier to say what's not connected than what is. What's true about the set

not being connected? I can somehow separate one from the other.

-

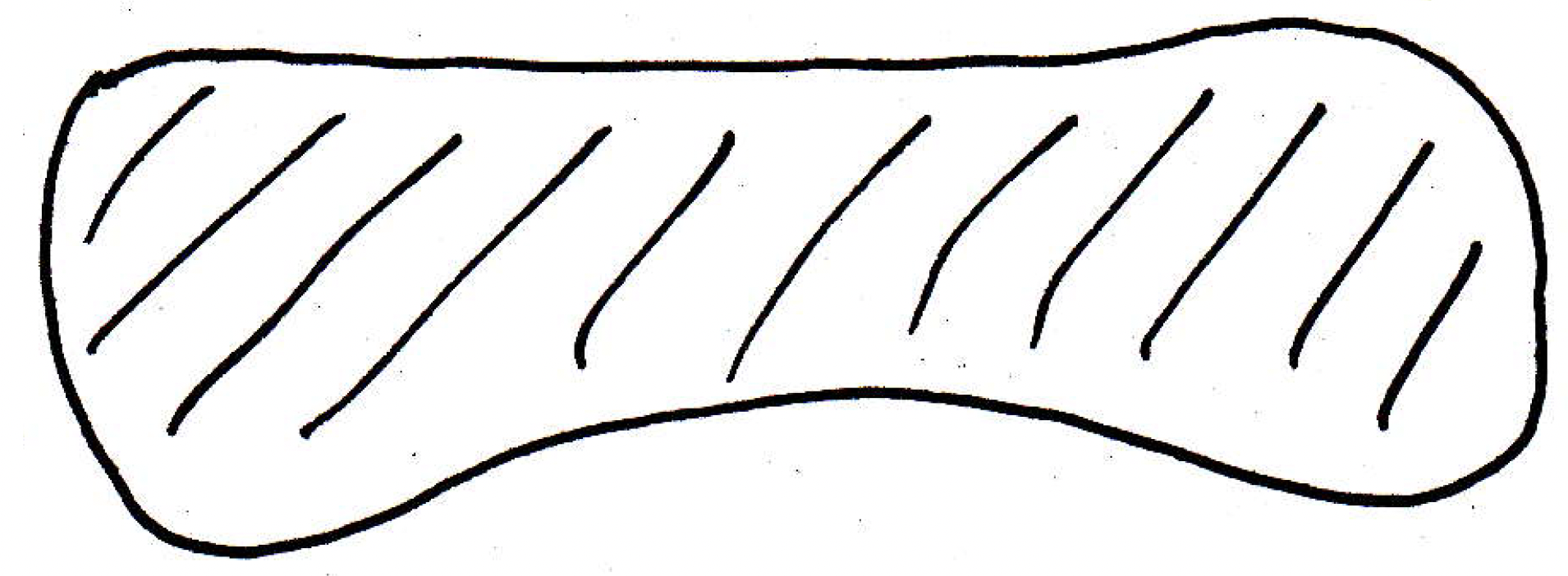

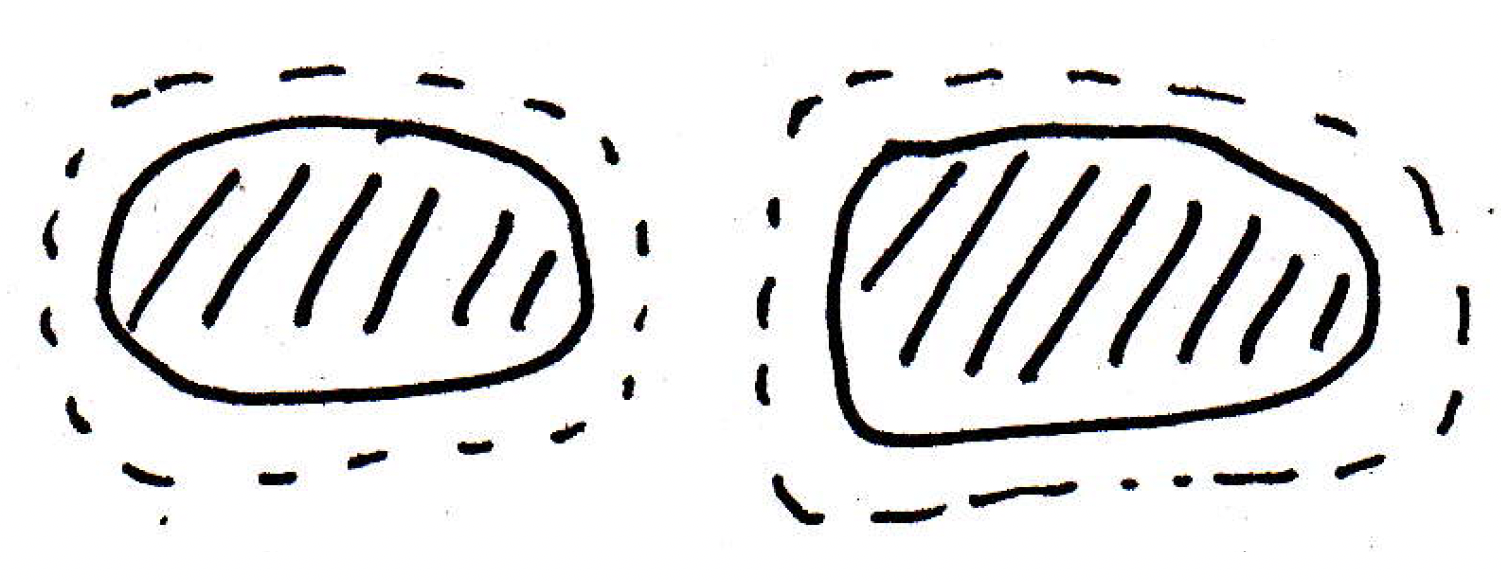

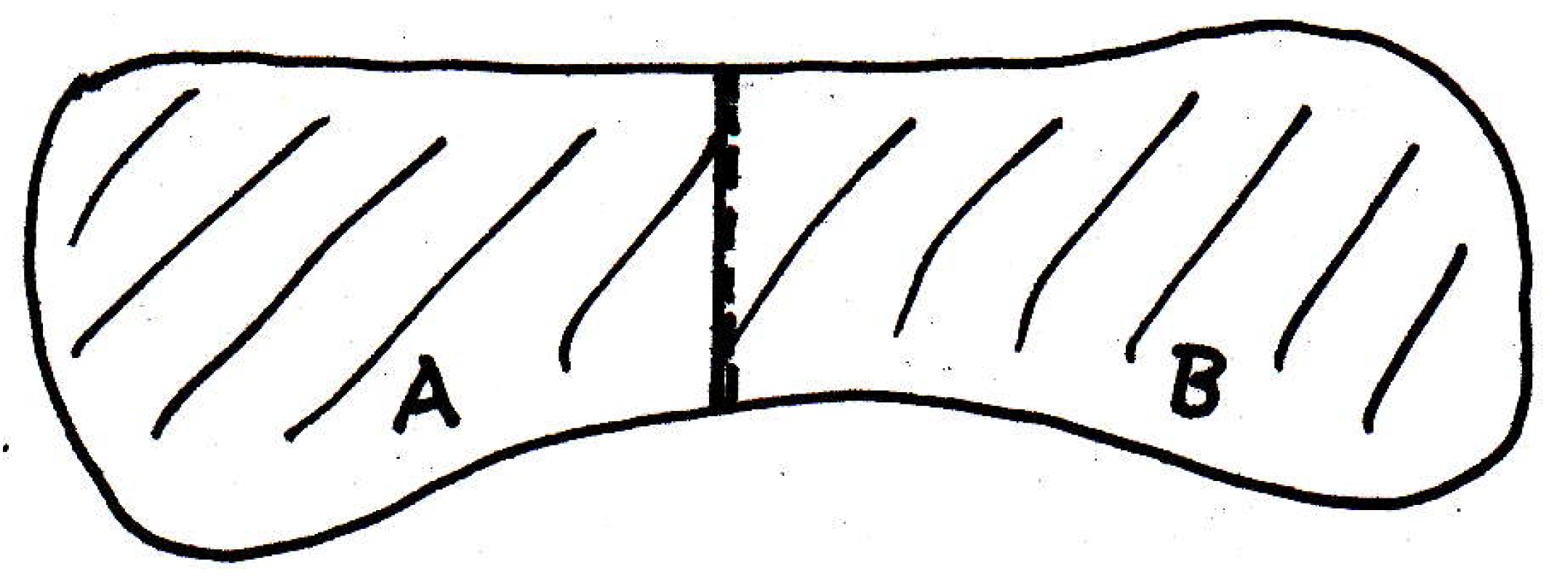

Student consideration: We could cover the seemingly not connected sets with disjoint open sets:

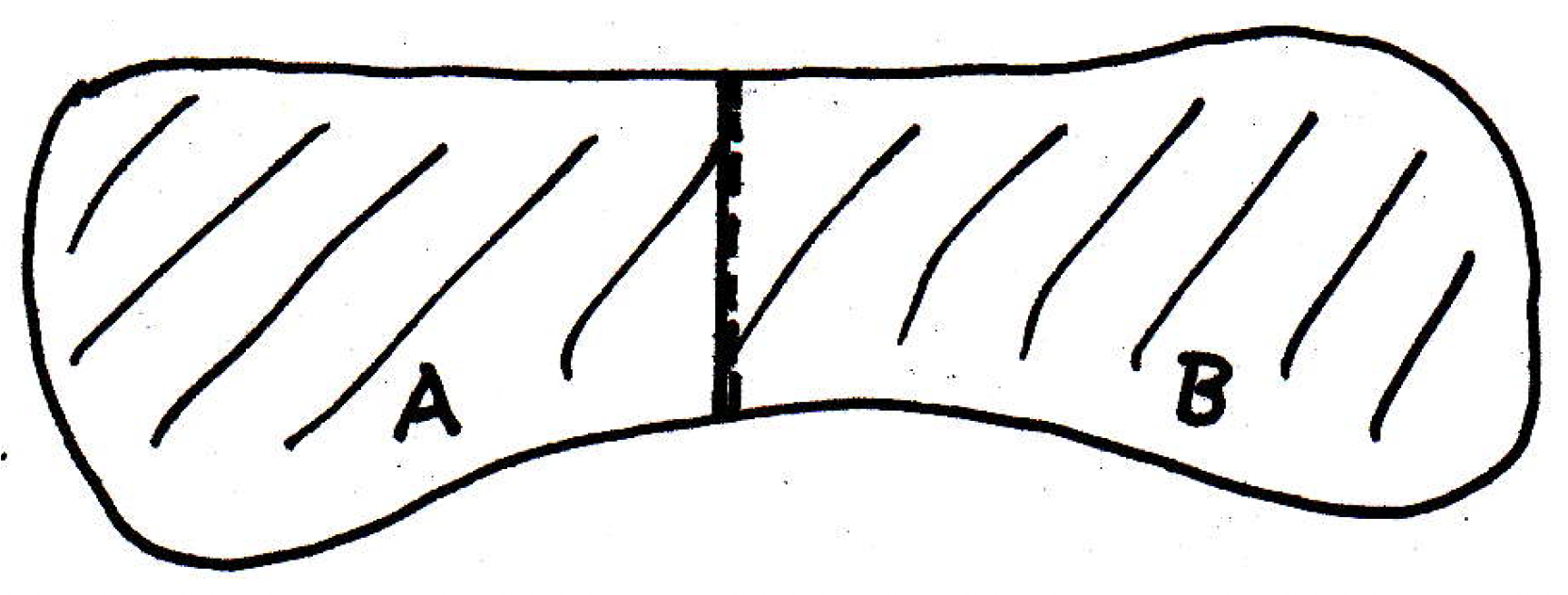

So we have two disjoint open sets that seem to separate the two allegedly disconnected sets. And that would rule out the following picture, where we cut the original seemingly connected set into two sets, and , where contains the boundary but does not (indicated by the slight dashed line):

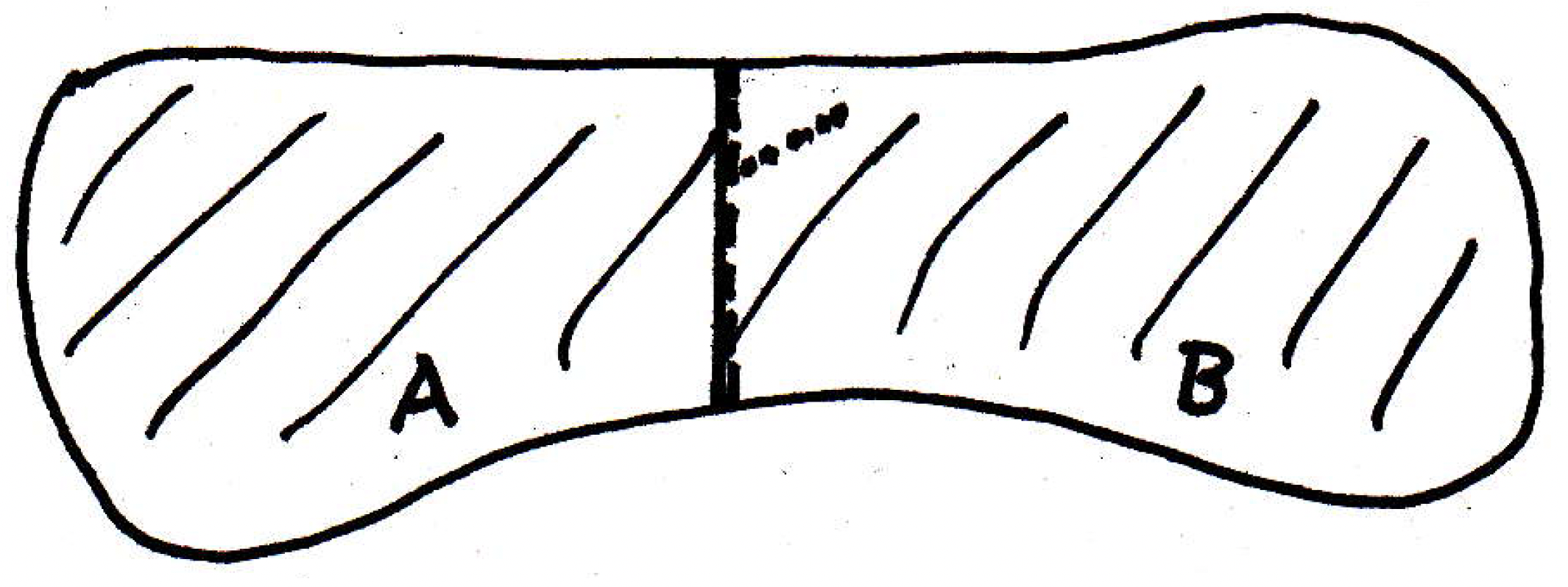

We could certainly cut such a set into two pieces, but we wouldn't want to call the sets and separated either, and the suggested criterion would prevent that. You can't put an open ball around and an open ball around without some overlap; that is, the balls would touch. The suggested criterion is a good topological definition for separated sets. The book uses a different notion which is equivalent, and the equivalent concept is as follows. Consider the following picture:

We will call the sets and above separated if no point of is a limit point of and vice-versa. This would not be true for the picture

because is it not true that some points of are limit points of , especially if we go from the side toward the boundary? Consider the following picture:

So we have the concept of what it means to be separated to prevent this sort of scenario.

Precisely, we say in are separated if both and are empty, where recall that denotes the closure of the set . (This is just precisely communicating what we just said, namely that no point of one is a limit point of the other.) This is what it means for two sets to be separated. Now we can say what it means to be connected.

-

Connected: We say is connected if is not a union of two nonempty separated sets. If we have two separated sets, then we call that a separation. So if you cannot find a separation of , then is connected. So the pictures above give a clue as to what that means. How about an example in ?

-

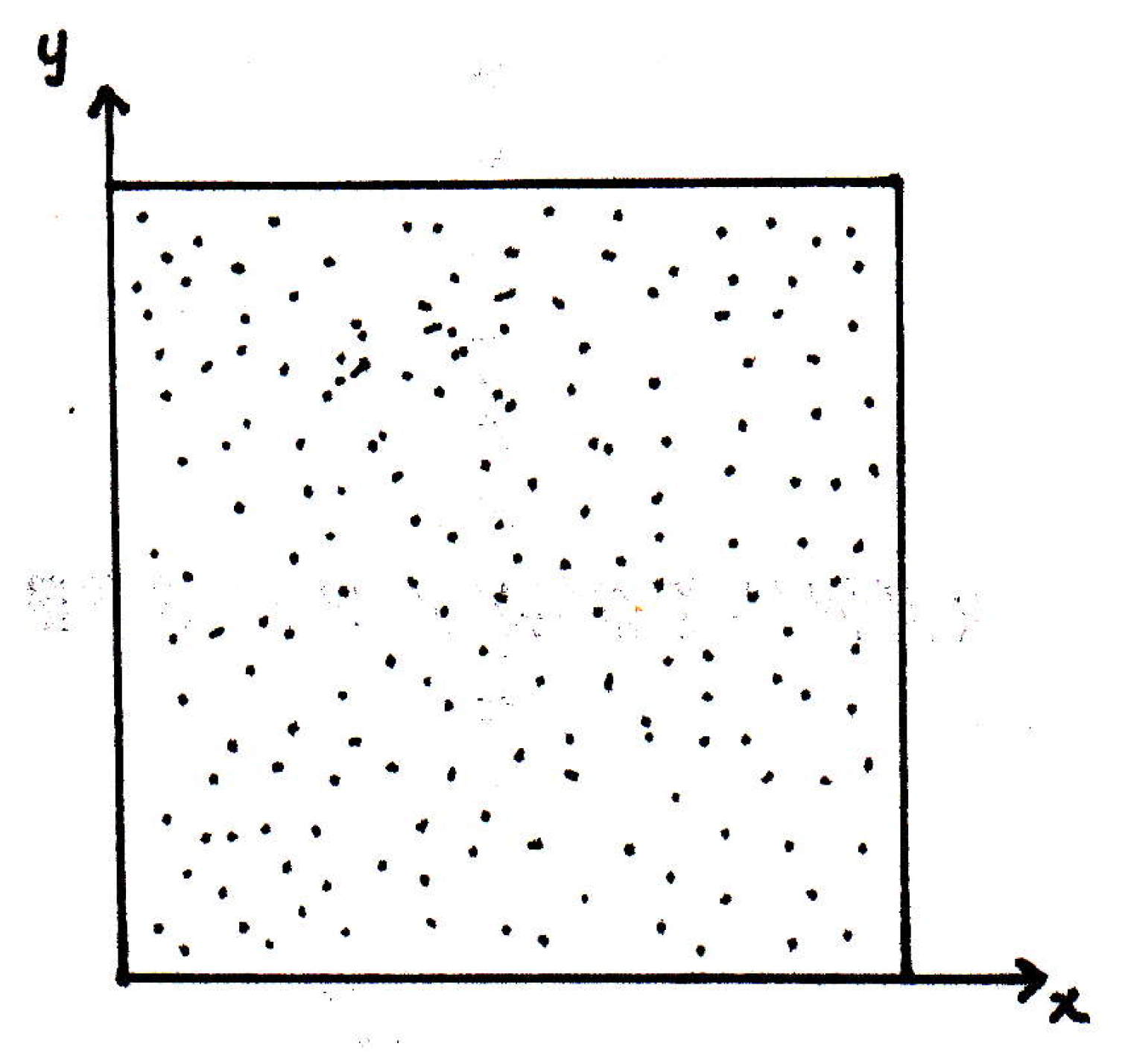

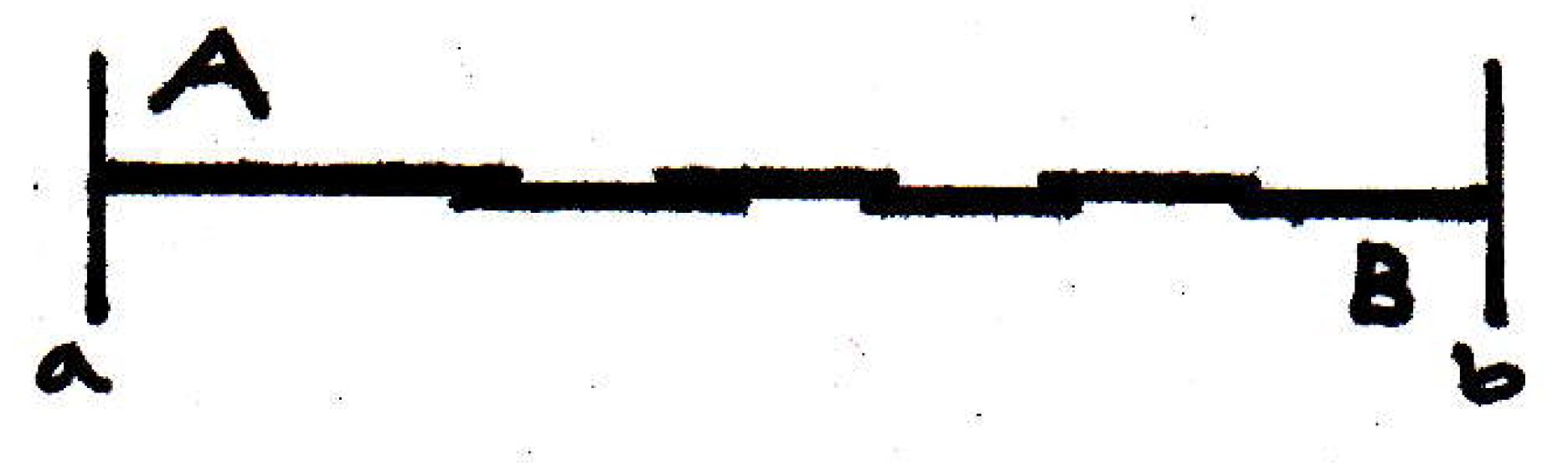

An example concerning connectedness: In , let's look at the set of all rational points ; that is, . Is connected or not? It might look something like as follows:

Is this set connected? No? If you say the answer is no, then you have to give me a separation. Find two sets none of whose closures intersect the other. The line would not work to split into two sets and because a lot of points with rational coordinates lie on that line. We want the separation to be one whose union is the whole thing. Something like making two sets such that one set is the set of all points and the other set , it turns out our desired separation is not true because their closures include the diagonal.

What about looking at the line ? Clearly this line has no points of on it. We can let the dashed line partition into two sets, and , where is the set of all points to the left of and is the set of all points to the right of :

We then have , as desired, and can we say why does not intersect ? Any point on the right side of the line (i.e., a point in ) cannot be a limit point of a point of the left side (i.e., of ) because the point on the right has a ball around it that completely avoids the line . If has any limit points, then they would be on the line , but they will not be over it. So the limit points of both sides can actually intersect, but here we only demand that one set does not intersect the closure of the other; that is, we must have that and are empty. Return to the following picture

what this means is that you can actually allow the open sets to overlap, but they cannot do so for points in . So the characterization above is true when you think of and you use use the relative topology on ; that is, you think of as the whole space. This brings up another definition that may be useful that is not in [17].

-

Relative connection: The set is connected in the relative sense (i.e., we are thinking of as its own space) if is not the union of two relatively nonempty nor trivial (i.e., "the whole thing" \ldots otherwise the other one would be empty) open sets in . If were the union of two open sets in , then what would the complement have to be? The other set. And it's closed. So another way to say it is that is connected if is not the union of two relatively nonempty nor trivial closed sets in . In sum, two sets covered by open sets in the whole space are automatically separated in . So if we just restrict ourselves to , the fact that both sets are open means that they're also both closed, and therefore they're both clopen in . And therefore the closure of a set in is just itself, and so it well never intersect the other set. So this is all taking place in in a relative sense. For the most part, we're not using these definitions, but it's good for culture. You'll encounter this in topology.

But if you're viewing as being embedded in a larger space, then you have to use the definition furnished in [17], namely that a set is said to be connected if is not the union of two nonempty separate sets.

-

Examples of connected sets: What's an example of a connected set? Is the real line connected? Can we show that? Let's maybe show something a little smaller. How about the set ? Yes, the interval is connected. Let's prove this. To show something is connected, it will generally be easiest to use a proof by contradiction. Because if a set is not connected then there exists a separation, and you can work with that.

Suppose is not connected. Then there exists a separation and , with . Maybe contains several different pieces, and contains several different pieces as well:

The set could also contain the endpoint . Although the picture may look like it, we don't mean that is necessarily contained in . So what's wrong with this picture? We're trying to get a contradiction. What's true? Well, we have the and . So we have to find a contradiction in the picture. Where would be a good place to start? Possibly some endpoints of intervals. How about the rightmost point of also known as the supremum of . Let . Then because is either in the set or it's a limit point (i.e., approached by points of ). So we must have or if it's not, then anything smaller must not be an upper bound so there has to be a point very close to the supremum. So if , then . So we must have . But if , then by definition of separation. So if , then there exists an interval containing no points of . But and are the whole set . So the interval must be all in . But why is that a contradiction? Because ; hence, for any , it could not be the case that is all in .

But what if ? We would not get our contradiction anymore because there isn't anything beyond . So what could we do? We could use the infimum of . This proof really could have probably been made a lot easier by just looking at the infimum of or by starting with the set that doesn't contain .