9 - Limit points

Where we left off last time

What did we talk about last time? What's a useful review from where we left off and where we were going?

-

Metric spaces: We began discussing this concept of how you put a notion of distance on a space of things so a metric space is really a set together with a notion of distance. Last time we left off discussing a very important concept, that of a limit point. Recall that represents a metric space where is the set and is the metric that gives the notion of distance for objects in , and the metric satisfies three properties:

- Nonnegativity and zero if and only if the points are the same.

- Symmetry

- Triangle inequality (this is often the most interesting property to verify as to whether or not a proposed notion of distance is actually a metric)

-

The usual metric: We've seen one example, namely the usual metric. So when you say , what you really mean is ; that is, you want to talk about together with the Euclidean metric , where this is given by the absolute value of the difference if it's a real number (so ), and in higher dimensions it's the square root of the sum of the squares of the differences of the two vectors. But there are lots of other metrics! There's the staircase metric, which basically said instead of square rooting the sum of the squares of the differences we took the sum of the absolute values of the differences between the coordinates so that basically measures how far it would take to walk from point to point if you only used north, south, west, or east motion. So that's one notion of distance. We saw some examples last time on other spaces as well such as the space of genome sequences, where you might have a distance that just measures the number of places where two genome sequences differ. There are lots of sets you might be interested in.

-

Exotic metrics: There are some vaguely exotic metrics out there too. For example, we might have , where is any set and represents the discrete metric. What's a discrete metric? Well, it basically says let's take the distance between and to be either zero if or one otherwise; that is, we have the following:

Is actually a metric? Does this satisfy the triangle inequality? If the points are different, then we have 1 on the left-hand side and either 1 or 2 on the right-hand side. If the points are the same, then it holds trivially. So what is the discrete metric really doing? It's basically asking whether or not two points are the same. If they are not, then we think of them as having distance 1 from each other. So imagine the real line with the discrete metric. That's basically a cloud of points that are all distance 1 from each other since none of them are the same. So somehow this idea of a metric begins to create a geometry which is different from the usual geometry (i.e., using the Euclidean metric). The real line with the Euclidean metric looks exactly as we expect it to, namely a straight line extending infinitely far in two directions, but the real line with the discrete metric looks like a cloud of points, an uncountable cloud of points, where all the points are a distance 1 from each other. The associated notion here is, of course, once you have a metric, you can start talking about which points are close, and one way to gather close points together is to talk about neighborhoods or open balls, where an open ball or a neighborhood is basically a set that looks like a ball around a point. We often write to communicate this, where the visualization is as the center and a (dashed) ball surrounding with distance from to the ball, where the neighborhood is all of the points inside the ball. So neighborhoods tell us essentially which points are close together. When you take topology, you'll basically be redoing analysis just referring to open balls and ignoring or not referring to a metric.

-

Open balls and discrete metric: What are the open balls for a space endowed with the discrete metric? So if we have , the open balls are single points if or all of if . What would the notion of a closed ball be? What are the closed balls if, say, . The open ball is just a single point . The closed ball is actually the same thing in this weird space, namely the point . It's not so weird actually. The discrete metric is just asking whether or not two things are different (perhaps most useful to a computer scientist).

-

Limit points and balls: We have this notion of balls, and now we can define what it means to be a limit point. Now, of course, the motivation here is to give me some sense of when a certain set of points is getting close to another set of points. So, "When does a set 'approach' a point ?" We might have a couple of different pictures in our head. How might we capture this idea mathematically?

-

Limit point (definition): A point , where here denotes a metric space and all other spaces from here on will denote metric spaces unless otherwise specified, is a limit point of if every neighborhood of contains a point , where .

Examples of limit points

What are some examples of limit points?

-

Example 1: In , suppose . So we have the set of all positive reciprocals, where it's clear things are clustering a lot near 0. We have that 0 is a limit point. Why would 0 be a limit point? What's the justification? Well, it had better be true that every ball around 0 contains another point not equal to zero but is in (i.e., is a reciprocal). Neighborhoods of look like .

-

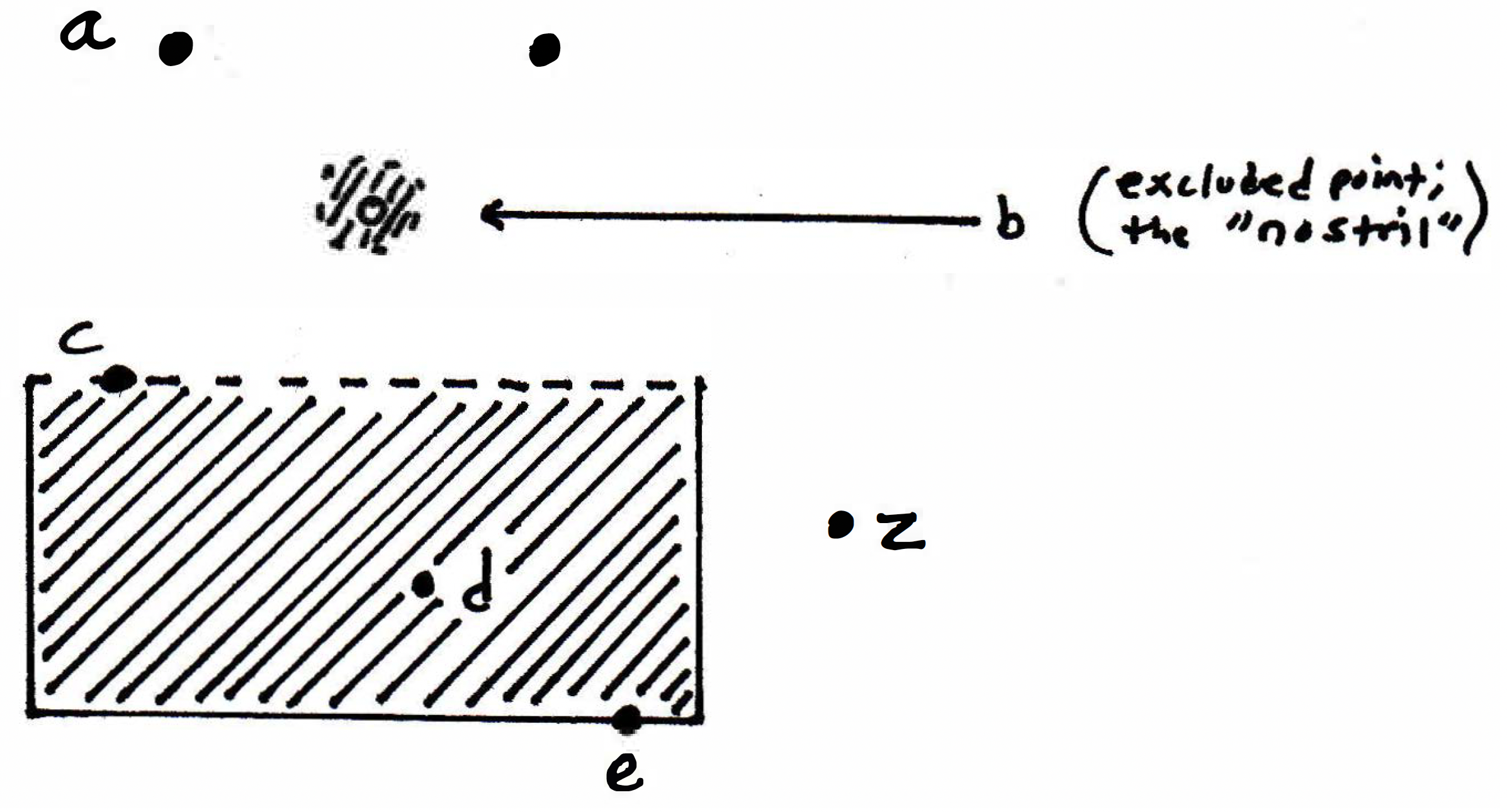

Example 2: In , suppose we have the set defined in the following way (let stand for a point outside of the set ):

Note that point is excluded from what looks like a nose. (You can think of it as a nostril of sorts.) Point is on the boundary. Which of the labeled points above are limit points of the set ? We see that and are not limit points while , , , and are limit points. When is a point not a limit point? Learning to negate a definition or a condition is a useful skill. So let's spend a moment talking about that. What does it mean to say that a point is not a limit point?

-

Not a limit point: A point is not a limit point of is there exists a neighborhood of such that does not contain any other points of . One question is if you have a limit point, then does an open ball have to contain infinitely many points? We'll answer momentarily. As an aside, it's useful to note that the term "topology" refers to the set of open balls so a collection of open balls is called a topology. To see why and are not limit points in the picture above, all we must do is find some open ball around or that does not contain any other points in the set , and that is easy to do, but we claim the way and are not limit points is slightly different in character. Even though they're not limit point, is in the set whereas is not. So we have a special name for points that are in the set but not limit points. The points that are in the set but not limit points are called isolated points.

-

Isolated point (definition): A point is an isolated point of if and is not a limit point of . Are there any other isolated points in the picture above? The nonlabeled point that is in is an isolated point (i.e., the right "eye"). Anything else? No! How about for the set ? All points of are isolated; for example, one one-millionth is an isolated point because if we look at , then I can find a small enough neighborhood around that misses and , namely the neighborhood . (Note that and so cannot be an isolated point.) The "eyes" in our picture are isolated too. For the set , now let's look at . How is different from ? The point has the property that if you take a ball around it that there is a ball around it that not just intersects but the whole neighborhood is inside. That's kind of on the opposite extreme of being isolated. So we have a name for that too. We call such a point an interior point.

-

Interior point (definition): The point is an interior point of if there exists a neighborhood of such that is completely contained as a subset of . Is that true of any other point not labeled in our picture? Yes, especially the points around the nose. What's the negation of the interior point definition? (Think about this.) Are there any interior points of ? Our set actually has no interior points. Is the point an interior point of ? No. Why not? Because is not in .

-

Example 3: In , consider , , and ; then in with the discrete metric, consider the same sets. And determine what the limit points are, the interior points, and the isolated points. Note there are essentially 6 examples to grapple with here.

- In , under the usual metric, we note that has no limit points. Why not? Is it true that every neighborhood of contains a point of the empty set that's different from ? No, because there's no point in the empty set. So the empty set has no limit points in the usual metric.

- In , under the discrete metric, we still have the same problem. So the empty set has no limit points here either.

- In , under the usual metric, every point in is a limit point.

- In , under the discrete metric, there are no limit points. Why? Consider a point . Is there a neighborhood of that completely misses other points under the discrete metric? Yes, because the balls are points, and the whole thing.

- In , under the usual metric, the set has every point of as a limit point. It doesn't matter where our point is. Are there isolated points of ? No. Because if it's a limit point, then it's not an isolated point.

- In , under the discrete metric, the set has no limit points much for the same reason as why did not above.

Does , as a subset of itself, have any interior points if the metric is discrete? In discrete, every point is actually an interior point.

-

A theorem concerning limit points: If is a limit point of , then every neighborhood of contains infinitely many points of . We will give a proof by contradiction. Suppose there exists a neighborhood of with only finitely many points of (if one of the points turns out to be itself, then simply ignore it and look at the minimum that is nonzero, where the following fleshes this out more), say, . Then there will be a least distance from one of these points to the point because every finite set of numbers has an infimum that is achieved. Let . Such a minimum exists because the set is finite. But the neighborhood has no points of , a contradiction.

Important terms

What are some more important terms?

-

Open sets (definition): We have a concept for a set that looks like the nose in the picture for that has the property that every point is an interior point. Such a set is called open. More precisely, a set is called open if every point of is an interior point of . In the example for , the "nose" of is open. Why is it open? Basically, an open set looks something like a dashed curve or loop or some set that doesn't have its boundary. What if the nose had two nostrils? Then yes, it would still be open. In , what do the open sets look like? Is the open ball open? Consider the interval . Is it open? Yes! That's why we often call it the open interval. Well, it's certainly true that no matter which point you pick that there's a ball around it that's still contained inside the set. What about the empty set? Is it open? Yes, it is vacuously true (i.e., every point of is an interior point of because there are no points in ). What about all of ? Is that open? Yes, because we can clearly find an interval. What might it mean for a set to be closed?

-

Closed sets (definition): First, note that a set being "closed" is not the negation of that set being "open." Why? Well, we say a set is closed if contains all of its limit points. (In some sense, a closed set is a set with its boundary included.) In , is a point closed? Does it contain all its limit points? What are all of the limit points of a single point? There are no limit points! So it contains all its limit points. So in , we have that is closed. Is the interval closed? No, because and are limit points. How about the interval ? Yes, that's why we call it a closed interval. Now, the intervals and are neither open nor closed. These intervals are often called half-open intervals. The idea is that they are not open and they are not closed either. Is the empty set in closed. It contains all of its limit points which are none! Is closed in ? Yes, it contains all of its limit points as well. So and are both open and closed. These are called clopen sets. This suggests something important actually, namely this idea that if you have a set that isn't closed, then there is a way to try to close it. For instance, the set we considered earlier, is the rectangular piece that represents the mouth closed? Clearly not. But how could we make it closed? We could give it an upper lip perhaps. The claim is that it is then closed. It may seem obvious but it may not be as obvious as it looks. So the mouth of is not closed currently. Is it open? No. So it's neither open nor closed. Can we close the mouth? Here's the idea: The idea is to look at , which we'll define below.

-

The closure of a set: Let be the set of all limit points of . The closure of is , where is not standard notation. So one of the big questions you have to ask yourself is whether or not is closed.