2 - Properties of Q

Summary

-

We defined sets, relations, and equivalence relations.

-

We defined as a collection of equivalence classes:

where is the class of ordered pairs such that if and .

-

Another idea you can define using the notion of a relation is that of a function (something that will be used in more detail later). The idea of an equivalence relation is basically a way of grouping together objects in a set that you want to consider as being equivalent. And so when we defined the rational numbers, we defined them as equivalence classes of certain objects, and those objects are named by these symbols "," for instance. But the way you should think about them formally is as an object that represents a whole class of things. The first example of that might be the class

Of course, all of these ordered pairs represent the same thing. You grew up thinking you could call this class , , and so on — these are all the same thing.

The relation is the usual cross-ratio you are used to thinking about (i.e., provided that ). Recall that this relation is an equivalence relation; that is, this relation is reflexive, symmetric, and transitive.

-

We ended last time by constructing the rationals as a bunch of classes.

Arithmetic structure on Q

Today we want to talk about the arithmetic structure of the rationals; that is, how do we define an arithmetic structure on ? And in what sense does extend ? Our plan, then, is to talk about properties of . In particular, we want to talk about its arithmetic and order, and properties, and we'll see that that leads into a discussion about the algebraic structure of which is naturally a field.

-

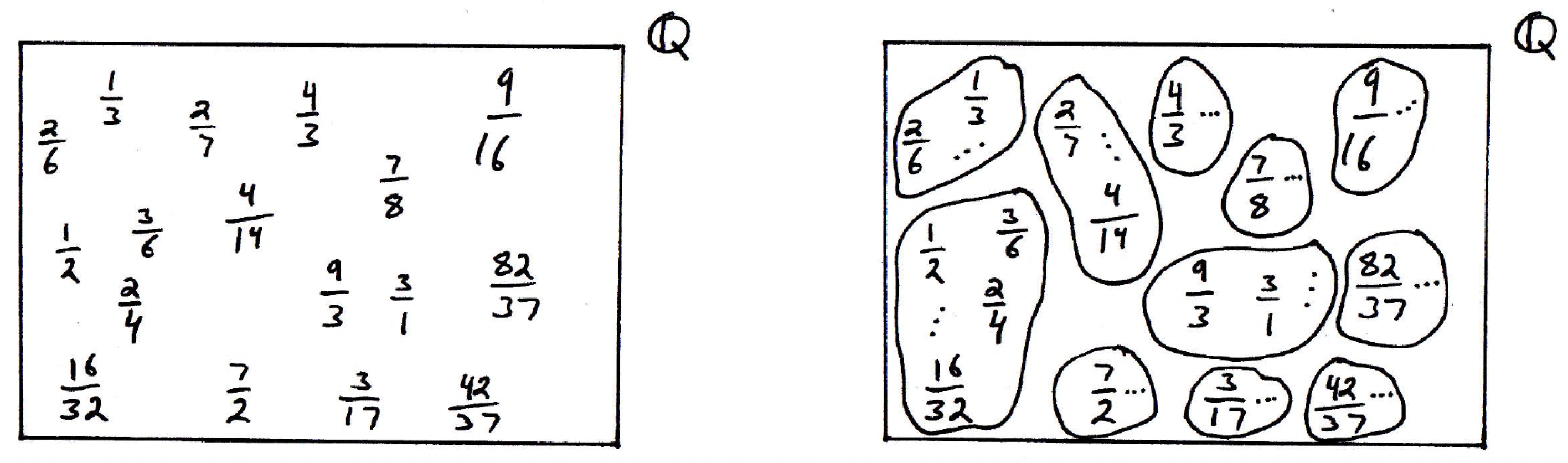

Addition: A natural first question is what we mean by addition of rational numbers. To set the stage a little bit, it's helpful to be reminded of the fact that all we have right now, as we've defined the rationals (which is our "universal set"), is a bunch of classes, and we will represent them as fractions instead of ordered pairs:

In the left-hand figure above, we have simply drawn a few equivalence class representatives. In the right-hand figure above, we have grouped the fractions in such a way that equivalent ones appear in the same partition or bubble. (This may be a good time to talk about the relationship between equivalence relations and partitions.)

Now, how are we going to define addition? It is important to note that we have agency in this matter. No matter what we choose, however, addition should be well-defined (i.e., unambiguous). In some cases, arithmetic operations for some mathematical objects may seem unnatural (e.g., multiplication of matrices). There should be some guiding motivation behind our definitions. So what might it mean to add infinite series exactly? Or multiply them? You get the idea.

In this case, we essentially want to add two classes together (recall that fractions are equivalence classes). What should that mean? What does it mean to add one class (i.e., a fraction) to another class (i.e., another fraction)? What would that mean? Let's take two stabs at it, one that is no good and another that leads to a desirable definition.

-

Definition (bad): Let's define the addition of two rational numbers and as

Why is this not a good definition? Besides the fact that it seems to be somewhat meaningless (another issue worth addressing) it has a more basic problem — the definition is not well-defined. For example, if we are instructed to add the fraction to the fraction , then we will have the following according to our rule:

Of course, is also equivalent to , and we can try to rewrite the above with this substitution (with the hope being that we will obtain a consistent answer of ):

This is clearly a problem. Anytime you are dealing with an object that is defined in terms of classes, the definitions you use should not depend on the representatives you pick.

Another example might be equivalence classes of college students. One way to define an equivalence relation is to look at all the freshmen, sophomores, juniors, and seniors. Class by class, and there are four classes, and these are equivalence classes. I want it to be the case that anytime I define something in terms of freshmen, sophomores, juniors, and seniors (i.e., the equivalence classes) that the answer should not depend on the person chosen (i.e., the representative). I might ask a question about college students. I might ask how many classes a student has taken. And the answer might depend on which class you're in but it shouldn't depend on which person you pick in the class as a representative. Of course, that particular question is not well-defined for the equivalence classes of college students (in the freshman class alone, many people take a wide variety of classes ranging from, possibly, as few as 1 to as many as, say, 7 — regardless, the result will depend on a particular representative of the class instead of being true for any representative of the class as a whole). What is a question whose answer is well-defined for the classes of students? Perhaps, "What year will you graduate?" This may be cause for concern for some, but for the most part what year you're predicted to graduate has a well-defined answer. We want the same thing for our definition of addition of rational numbers. In this sense, the definition of addition we proposed above is not well-defined and thus not useful. What we want is a notion of addition that does not depend on the representatives chosen. We want addition of classes to be well-defined.

-

Definition (another bad one): Let's now define the addition of two rational numbers and as

Is this definition well-defined? Yes! It clearly does not depend on what class representatives are used — it doesn't even depend on what classes are used! But it's completely boring and meaningless. Worthless you might say. So let's give it another go.

-

Definition (good): Let's now define the addition of two rational numbers and as

What would we have to do in order to show that this definition is well-defined? We must show that if and , then .

-

-

Showing that addition of rationals is well-defined: We must show that if and , then . Consider the following:

- Given , we have , where .

- Given , we have , where .

- We want to show that . By the definition of , this means we want to show that .

- Consider the following:

From the above, we see that the addition of rational numbers is well-defined.

-

Multiplication: By now, of course, you know that we are trying to create arithmetic with some meaning, and you've already learned some of the meaning of multiplication so it makes sense to do this the way you learned in grade school. So if I want to multiply two rational numbers and , then I can define the product to be

You will need to check that this is well-defined. Again, that means that you are going to have to convert the above statement into a statement about ordered pairs, namely if and , then .

We have an arithmetic, and it's good news that addition and multiplication are well-defined, and there's a reason for that. It's because it has a physical meaning, the one you grew up learning.

-

Showing that multiplication of rationals is well-defined: We must show that if and , then . Consider the following:

- Given , we have , where .

- Given , we have , where .

- We want to show that . By the definition of , this means we want to show that .

- Consider the following:

From the above, we see that the multiplication of rational numbers is well-defined.

Q extending Z

In what sense does extend ?

We've defined rationals in terms of integers, but I want to know in what sense this new construction really extends the integers. (See the note in the first lecture about embeddings and isomorphisms for a more algebraic treatment.)

-

First things: Well, the first thing you have to tell me is which elements of correspond to a particular integer. The integer 5, for example. What class is equivalent to 5 as an integer? The class . We say that corresponds to 5 or, more broadly, corresponds to , where is an integer. This correspondence would be kind of uninteresting if it weren't also for the fact that the arithmetic also extends.

What you want to check is that behaves "like ." This is an informal way of saying that the subset of the rationals is isomorphic to . The correspondence is . We can check that and . What do we have now? We have a picture that's no longer looking like a bunch of random elements of , where some elements belong to the same equivalence class, but now, somehow, has a structure that tells me how I might add certain elements, multiply elements, and some special classes behave just like the integers do. Now what? We have this thing that extends the integers, but the integers also have another property. There's an ordering; that is, has an order.

Order relations

What is an order relation exactly? We note that there seems to be an order relation on , but does have an order relation?

You grew up learning about what the order might be, but let's think carefully about how we might define a notion of order that is consistent with the ordering of the integers. First of all, what is an order? Hint: It takes two things in and it describes some kind of relation between the two. It's a relation! And what sort of property should it satisfy? We'll define it as follows:

Definition (order). An order on a set is a relation satisfying

- Trichotomy: If , then exactly one of these is true:

- Transitivity: If and if and , then .

If you have an order on , then you call an ordered set.

-

Order on : In the integers, what is an order? You have to be somewhat careful here.

- Student attempt: We say if is positive. I like that, but what is positive? Greater than zero. But greater depends on an order so you've defined order in terms of positive and positive in terms of order, and we want to avoid that, but that was a nice try. But you have the right definition, so we just have to decide what positive means. What is positive? What does it mean for an integer to be positive? The absolute value of is . We haven't defined absolute value.

- Correct result: I know you're trying to define positive in terms of other things, but why not just say what positive is? Let's just write down a set. In , we are going to say that if is positive, that is, in the set . By the way, there are many other notions of order you can consider. We just gave one. But there are lots of other ways to order the integers.

- Student attempt: We say if is positive. I like that, but what is positive? Greater than zero. But greater depends on an order so you've defined order in terms of positive and positive in terms of order, and we want to avoid that, but that was a nice try. But you have the right definition, so we just have to decide what positive means. What is positive? What does it mean for an integer to be positive? The absolute value of is . We haven't defined absolute value.

-

Order on : In , we can say if OR ( and ). This is called the dictionary order for obvious reasons.

-

Order on : Does there exist an order on ? We don't know what complex numbers are just yet, but for those who do, would the dictionary order described above work for the complex numbers? Well, first of all, does it satisfy the trichotomy law? Sure. Is it transitive? No? What would keep it from being transitive? We're just checking dictionary order. There's nothing to keep it from being transitive. Right? So it would work for the complex numbers as well if we are thinking of complex numbers as ordered pairs of real numbers.

Note on subtraction of rational numbers: We will define subtraction as adding the negative of, where negative is multiplying by . We know how to multiply two rationals, and we will associate to the rational number (recall the correspondence between and ) and perform the multiplication that way. In particular, what that means is that anytime you want to subtract two rationals that's the same as adding , and just treat as an integer. We know how to multiply negative numbers that are integers.

-

Order on : How are we going to define an order on ? How about we do something very similar to what we did for ? We are going to say is positive if . We've just made a definition involving the rationals — what's one thing you should worry about when making a definition involving a bunch of equivalence classes? That it's well-defined! To check this, you'd need to give me another member in the same equivalence class as , say . Then we have , and we can check that by working from there.

-

Proof sketch. Suppose is positive. Then by definition. Furthermore, suppose , whereby , with . Our goal is to show that we must have . First note that , whereby we may also conclude that (this is important to note in order to preserve strict inequality in the chain of deductions below) [see one of the lecture end notes on how is deduced from the given info]:

Given that the above definition of a positive rational number is well-defined, we will say that if is positive.

-

-

Note: It should be mentioned that sometimes we write "" for . We're already using the words "less than" and "greater than" to think about these symbols because they come from our notion of order that we've grown up with. Sometimes we'll also write to mean or .

Implications of ordering on : So we have just defined by what we mean by order on . Stepping back from what appears as rather tedious work, we no longer have this picture of as a box with jumbled elements all over the place. Now there's a way to think about the rationals the same way we think about the integers. We think about the integers as ordered living on some kind of line perhaps, where "" is to the left of "" if "" is less than "." So the rationals actually live on such a line as well.

A new picture of Q

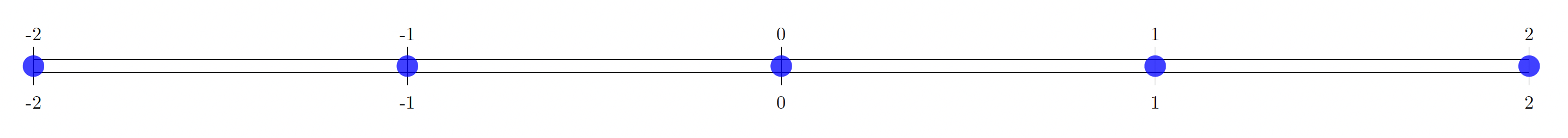

We have this notion of order for the integers:

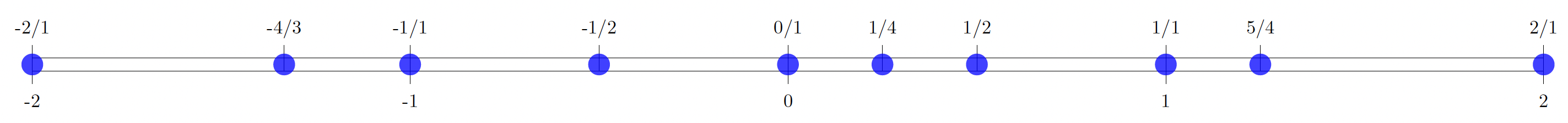

There are some rationals here and we can check that, for instance, is less than 1 and greater than 0. And is between 0 and . And so on. We can give a modified picture below (note the correspondence(s) between the rationals and the integers such as and and so on):

Of course, there are many more rational numbers. The new picture of (i.e., as an ordered set as opposed to just a jumble of equivalence classes) is good enough to answer a few questions.

-

Good enough: The set is good enough to solve some questions we might be wondering about. For instance, if I have 3 cakes, and I want to divide them among 5 people, and I might be interested in equal shares for everybody, then I need to solve the equation . Is there an integer solution here? No. Is there a fraction? Yeah! In fact, it's clear what that fraction is because of the multiplication rule for rational numbers. We can see that satisfies this equation. Why? Well, 5 is the same as , and we would thus have the following:

This is just the arithmetic you learned in grade school, but now it's on firm foundations. From here on out, you can assume you know the properties of the rationals, lest you are asked something foundational. So rationals are good enough to answer some questions, but there are some questions for which the set is ill-suited. It cannot be used to solve all equations, for instance.

-

Not good enough: The set is not good enough to solve for rational .

-

Illustration (proof that is irrational): The equation has no solution in . Another way of stating this is, "The square root of 2 is not rational." But let's avoid saying that here because we have not defined the square root of 2. All we're saying is that in the rationals there is no solution to the equation . It's a classic proof by contradiction.

Proof (by contradiction). Assume has a solution in ; that is, suppose , where , and assume that are in "lowest terms" or have no common factors. Then ; hence, . Then is even (i.e., is divisible by 2), whereby we see that is even (because if were odd, then would be odd). We let , where ; hence, . Then . Then is even, hence is even. This contradicts the fact that and are in lowest terms. So, must have no solution in .

So we have the rationals. They have an order, they have an arithmetic, and they are good enough to solve some equations but not others. In order to try to figure out what it is that characterizes the rationals, we'll have to talk about some properties they satisfy.

The set Q as a field

What does it mean for to be a field? The rational numbers will have to satisfy the properties that characterize a field. Recall the properties of a field.

Field (definition). A field is a set with two operations , satisfying axioms:

(A1) is closed under .

(A2) is commutative.

(A3) is associative.

(A4) has an additive identity, call it 0.

(A5) Every element has an additive inverse.

(M1) is closed under .

(M2) is commutative.

(M3) is associative.

(M4) has a multiplicative identity, call it 1.

Note: In [17], we see that M4 concerns the field that contains an element such that for every ; that is, we are talking about a multiplicative identity. The requirement that seems very bizarre at first, especially for people who have not seen any abstract algebra. A nice discussion may be found in [8] having to do with inconsistent systems and messing up the laws of arithmetic. There is also a discussion in [5].

(M5) Every element except 0 has a multiplicative inverse.

(D) distributes over .

For the rationals, what are the identity elements (additive and multiplicative)? The zero element is the class . The identity element is . We can check that all of the axioms hold for to be a field.

Is a field? No, because it does not satisfy (M5) in particular. We will see shortly that is a field. The interesting thing about is that it's not just a field but it's an ordered field. Despite what the name implies, an ordered field is not just a set that is both a field and has an order. What else would you like to be true about an ordered field besides the fact that such a set is ordered and a field? What else would you like to be true? Hint: For a field we have two operations, and that's nice, but the operations must play together nicely, hence the distributive property. Here is now a set, , that has these two structures (i.e., being an ordered set and being a field) — what else would we hope to be true? That the order and the field properties play nicely!

Ordered field (definition). An ordered field is a field with an order so that (aside: how would you like the order and the field properties to play nicely together? What would you suggest? There are two operations to a field. Maybe I want to know how they relate to the ordering.) order is "preserved" by the field operations.

- ,

- .

Note: Item (2) above is equivalent to, but differently stated, than what appears in Rudin. This way of stating the second defining property of an ordered field makes it clear that you are trying to have the order be preserved by the field operations.

So we have being an ordered field which basically says something about its structure.

We're heading towards constructing the real numbers. And our hope is that maybe the real numbers, whatever they are, might be good enough to solve the algebraic equation as well as other things. Hopefully they will also somehow contain the rationals or extend the rationals in some sense. And in some sense they will fill in the holes in the number line that we began to get a picture of. So it will also be an ordered field, but it will have a special property called completeness. So it will be called what is called a complete ordered field. So it will live on a line, like a number line, but it won't have the holes that the rationals do. The rationals don't solve the equation even though we know that's the length of a hypotenuse of a right triangle with two sides of unit length.

Equivlence of ordered field statements

Francis Su claims that the second condition he gives for an ordered field, namely

is equivalent to the one Rudin gives, namely

Let's prove this equivalence.

We will first show that Su's formulation implies Rudin's and then that Rudin's implies Su's, thereby establishing equivalence.

-

(): We are given by Su and trying to establish that follows for Rudin. To that end, begin by identifying with 0 in Su's formulation (i.e., ). Then the implication

becomes

or simply

If we now identify with and with , that is, and , then the equation above becomes

as desired. Thus, Su's formulation implies Rudin's formulation.

-

(): We are given by Rudin and trying to establish that follows for Su. Begin by recalling that, for any , and are two ways of saying the same thing; that is, for any . Hence, we note that . If we now identify with and with , that is, and , then the inequality

becomes

or simply

due to distributivity. Since , we may rewrite the equation above as

or simply

as desired. Thus, Rudin's formulation implies Su's formulation.

Since each formulation implies the other, both formulations are logically equivalent. As Su notes, he prefers his formulation due to the fact that it more clearly conveys the idea that you are trying to have the order preserved by the field operations.