23 - Discontinuous functions

Where we left off last time

What was the main idea concerning uniform continuity last time and what can be said about discontinuous functions?

-

Last time: Last time we talked about uniform continuity. In general, we've talked a bit about what it means for a function to be continuous, and we've seen many definitions of continuity by now. One of them was a metric definition which basically said that a function is continuous if close enough points are mapped to close enough points. So if in the target you want to be apart from the image of a point , then in the domain you want to be at most apart from . Now, of course, for a general function, the domain, that target , might depend on the choice of point . And the whole idea of uniform continuity is that that does not depend on . So the function uniformly spreads things apart; that is, things that are no more than apart get sent to things that are no more than apart. And that's for no matter where you are in the space. That was the idea of uniform continuity.

-

Discontinuous functions (what is there to say?): It may seem an odd question as to what we can say about discontinuous functions. Truly, they are just functions that are not continuous! But of what use is that? It turns out that there is actually more interesting behavior going on with discontinuous functions than may be evident at first blush.

-

Example 1: The first example of a function that is not just discontinuous but highly discontinuous is something called the Dirichlet function. It's actually a function that's not continuous everywhere. We will let

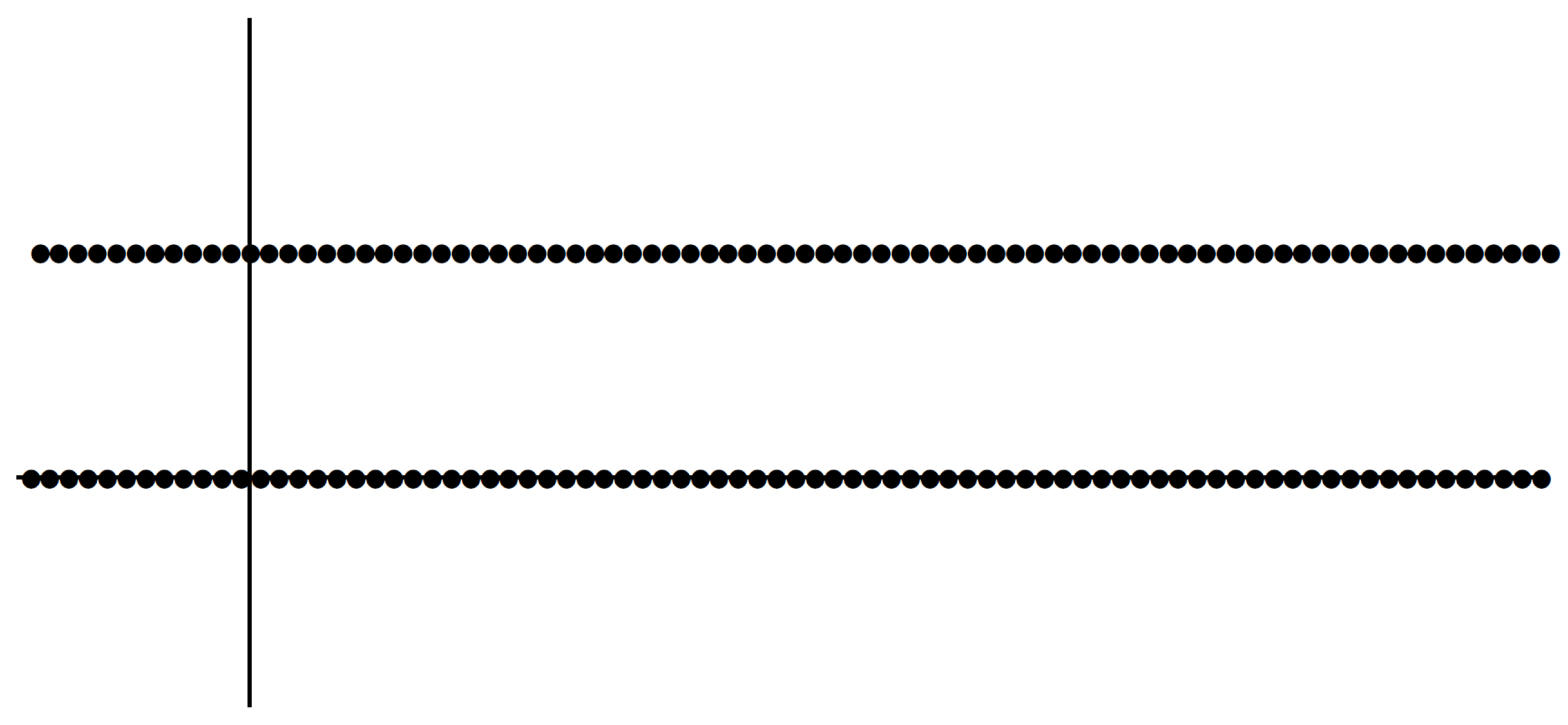

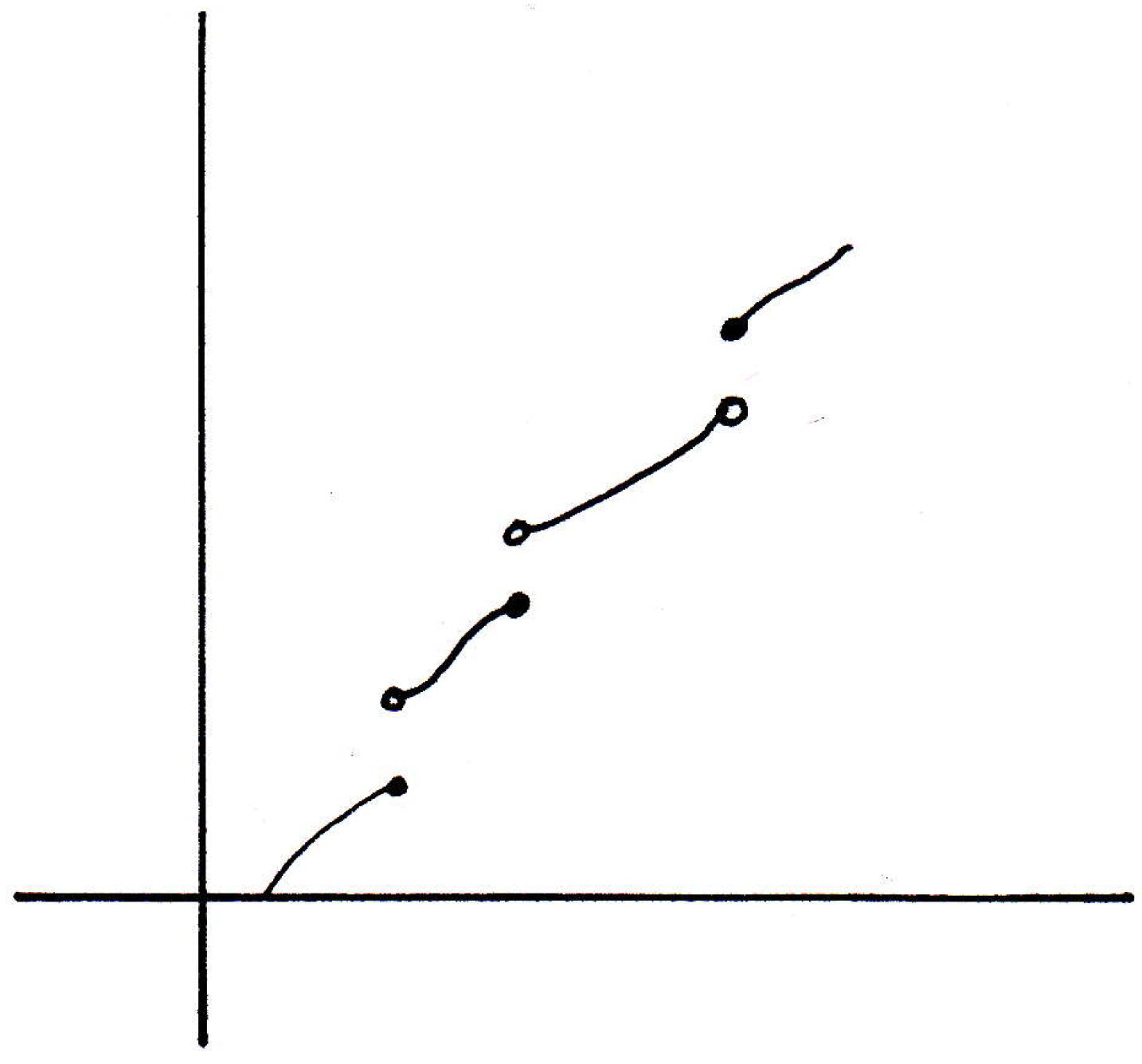

The way this function is defined makes it impossible to accurately draw, but it essentially looks like the following:

It certainly looks as though should not be continuous at any . Why is that? What's a brief argument for this? A very easy way to see this is that no matter what point you pick, if you take a ball around it, an open ball, it will contain rational and irrational points. Where is its image going to be? It's going to contain points that are close to 1 and close to 0. So if you pick epsilon less than, say, a half, then will cause trouble in satisfying the definition of continuity. So this function is clearly not continuous.

-

Example 2: Consider the following modified Dirichlet function:

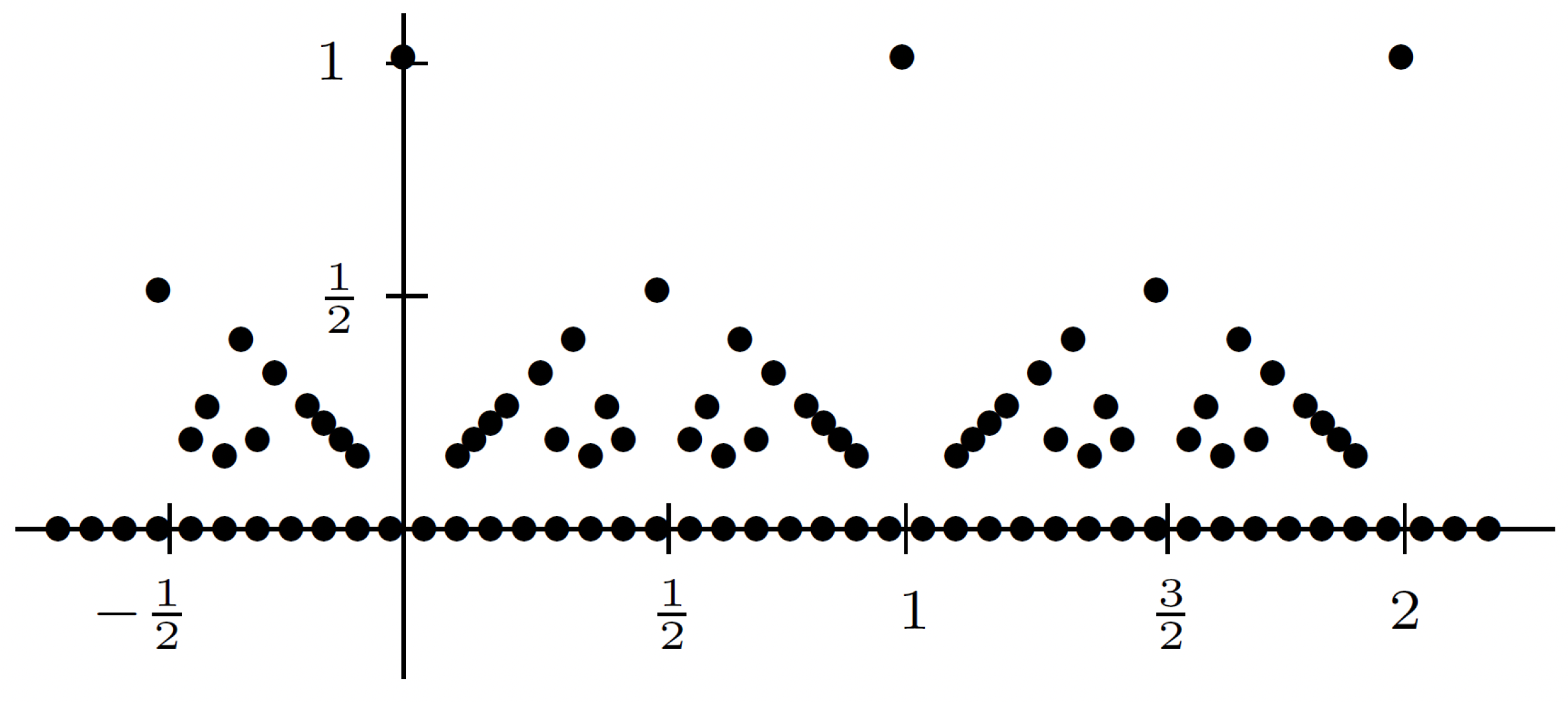

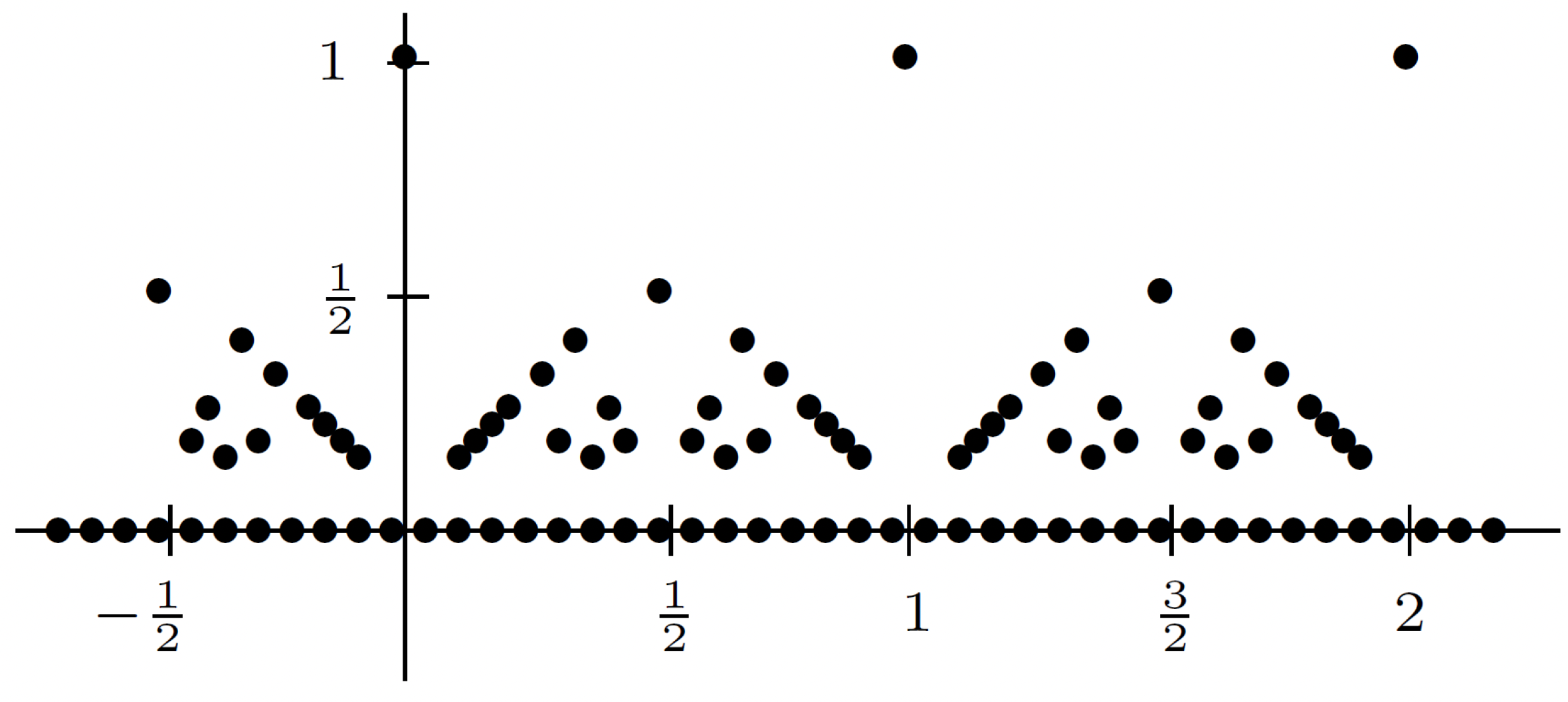

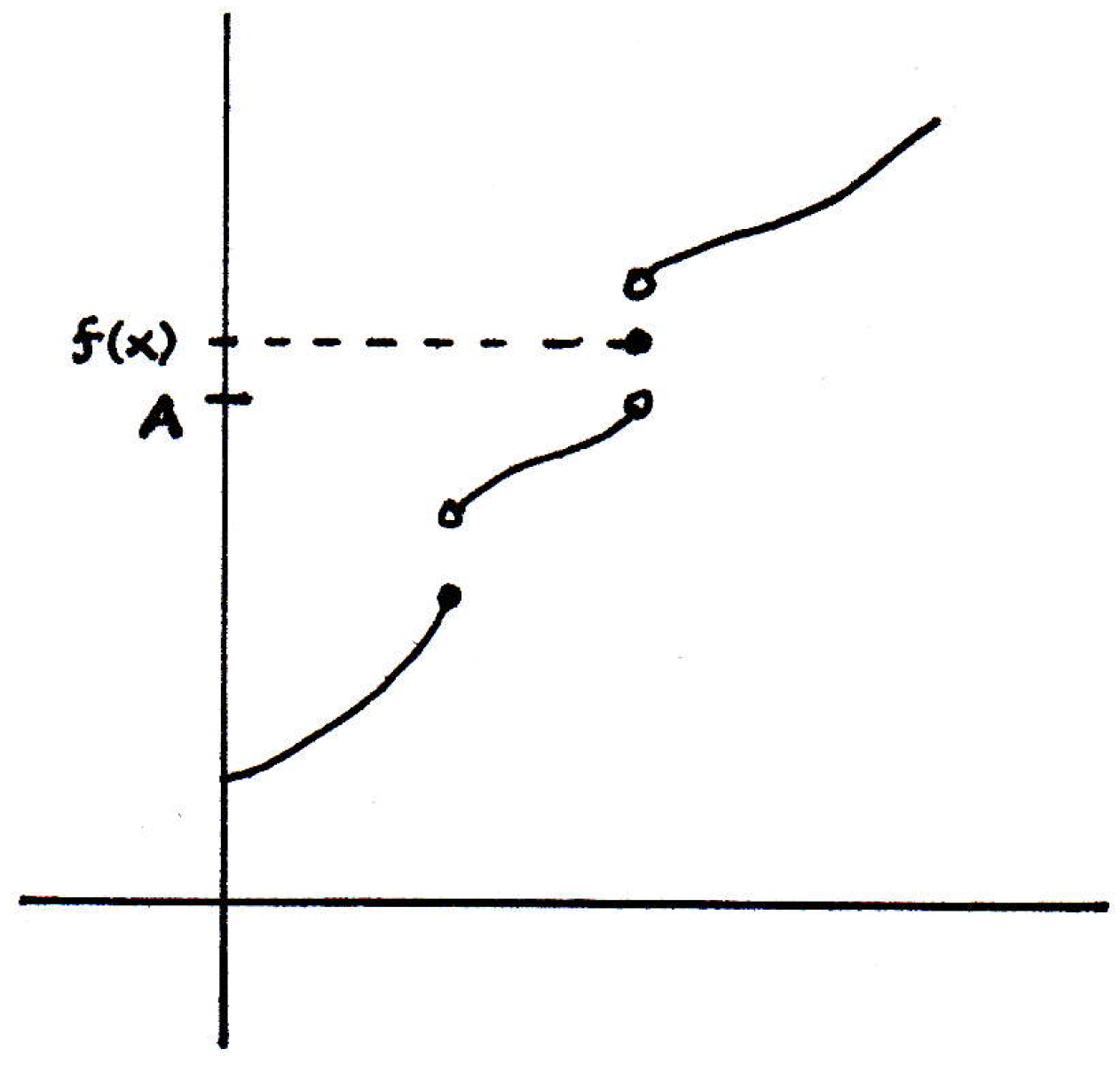

What will this look like? It will look something like the following:

So this function has a different value for different rationals based on the size of its denominator in lowest terms. It's a very cool function. If we take any particular value, then how many times would a horizontal line go above that value? Only finitely many times. So if my target were to look at an -ball around 0, then how many times does the given function leave the -ball around 0? Finitely many times. (See page 124 of this document or Exercise 4.3.6 in [11]. Also see [10] which is probably the best for making this clear.) No matter what is.

Note about finitely many points. As explained here, if we have , no matter what is, then at all nearby irrationals has value 0. Also, at all sufficiently nearby rationals different from , the function has value for arbitrarily large . (Spivak fleshes out this argument in more detail in [10]. Hence, in both cases, the value of is as small as you like for near but . That is, given , there are only a finite number of points where . So just get closer to than any of these points, and then you will have , and Spivak outlines this in more detail too.

So what is this function doing at the rationals? It's doing something nonzero. And it's pretty clear that at the rationals it's not continuous. What's happening at the irrationals? At the irrationals, say at , what's happening at that point? Its value is 0, and is there a neighborhood around it that will land in the target -ball around 0? If there's only finite many times the function leaves the -ball, then certainly this will be the case. What neighborhood should we use? How should we make ? Well, there are finitely many rationals where exceeds the -ball around 0. So take the minimum distance between this point and another that goes outside of the -ball. So you have a -ball for every . So while is discontinuous at all rationals, it is actually continuous at all irrationals. So, in fact, we see the set of discontinuities is a countable set, and it's continuous everywhere else. With the previous example, the set of discontinuities was uncountable. It was everything. What's interesting with this example is that where is continuous and where it's discontinuous doesn't have to comprise an interval.

Here's an interesting question: Is there a function that is continuous at all rationals but discontinuous at all irrationals? Let's try to learn some things about discontinuities, and maybe that will shed some insight on to what is happening. We can try to classify discontinuities.

-

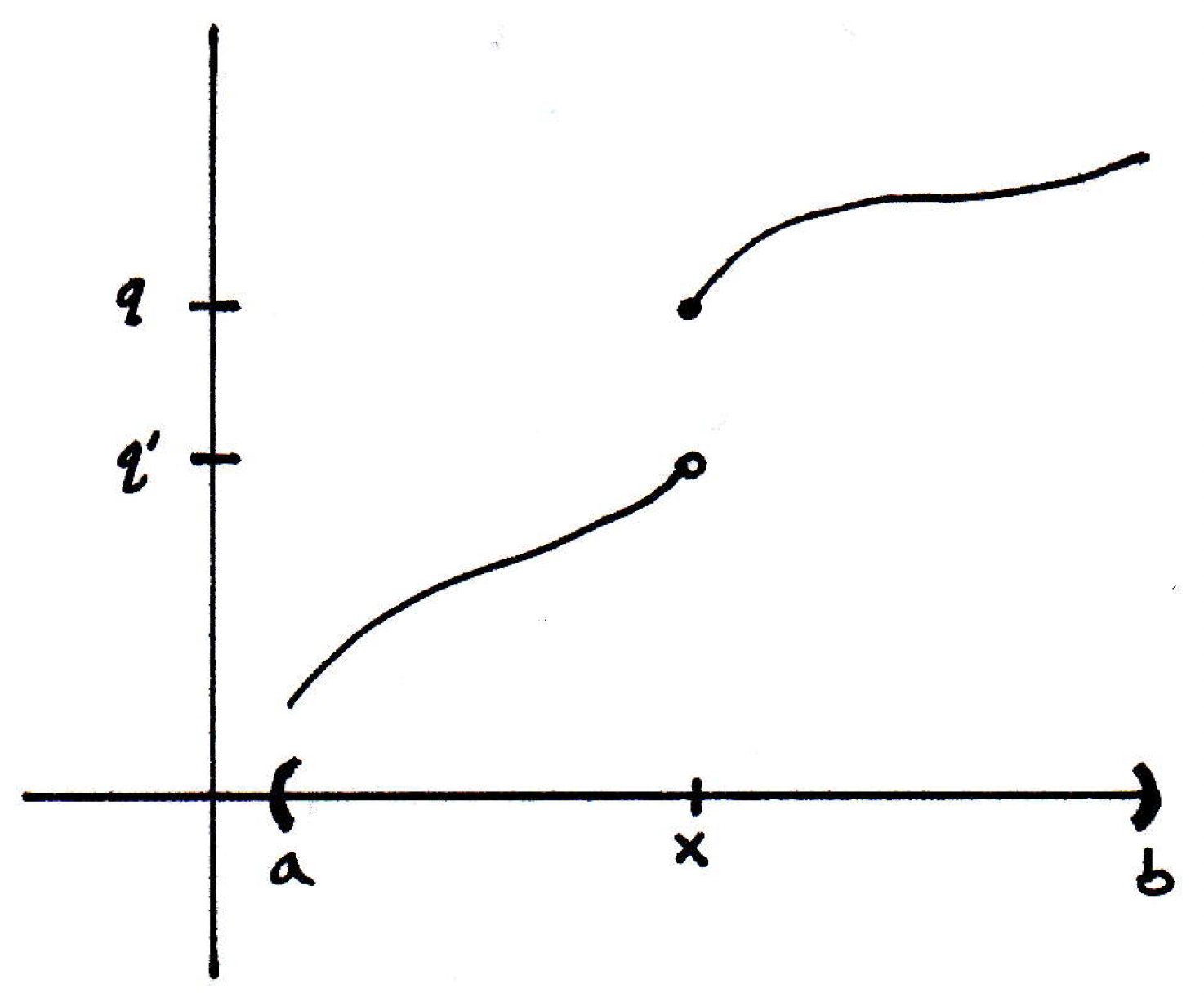

Classifying discontinuities: Suppose we have a function that looks as follows:

So we have a "jump discontinuity" of sorts. Suppose we took a sequence of points approaching from the right, and we followed the images of these points. What's going to happen with these images? It certainly looks as though they will converge to . More precisely, for all in with , we have . We will write or . So we now have a notation to describe what is happening here. So we actually have a right-hand limit, but the function does not have a limit at . But it has a right-hand limit and we denote it as above. Similarly, we'll write or, equivalently, . By previous discussions, we have exists if and only if . Now, if is discontinuous but and exist, then we will say that has a discontinuity of the first kind. (Sometimes people call this a "simple discontinuity.") Otherwise, the function is said to have a discontinuity of the second kind. So a question we should ask ourselves is whether or not there are discontinuities of the second kind. Basically, we want discontinuities of the first kind to be a kind of silly discontinuity. What about other kinds of discontinuities? Of course. Let's see.

-

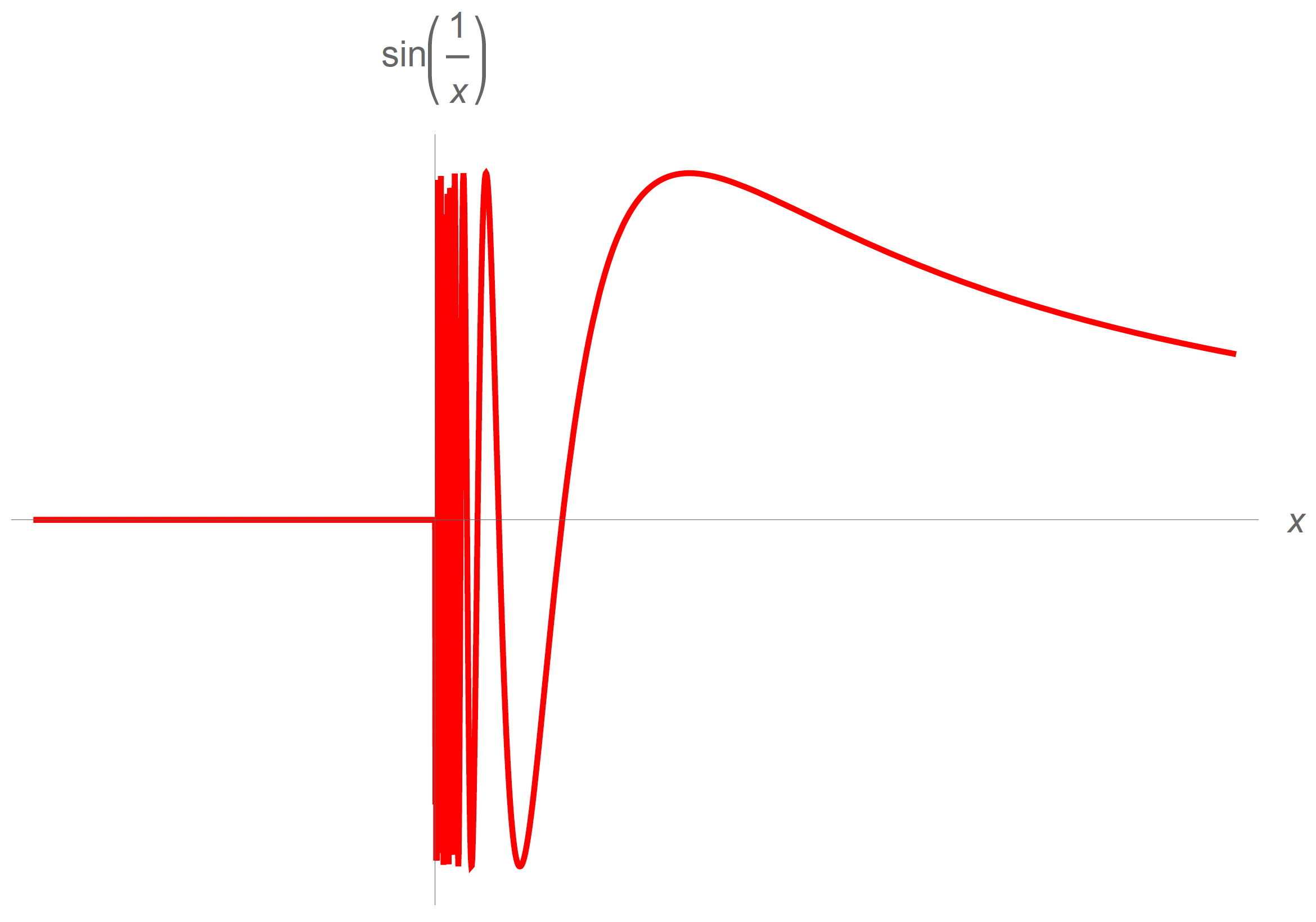

Discontinuity of the second kind: What would have to be true to have a discontinuity of the second kind? Maybe the limit doesn't exist on either side. Suppose we have the function

This curve will look as follows:

So at , there is a discontinuity of the second kind. Which limit does not exist? The one coming from the right.

-

Revisiting examples: Let's return to a previous example:

What kind of discontinuities did we have? Discontinuities of the second kind. All discontinuities are of the second kind. How about the modified Dirichlet function:

What kinds of discontinuities do we have here? It's continuous at all irrationals and discontinuous at all rationals. What kind of discontinuities do we have? Well, what about the discontinuity at ? Is it of the first kind or of the second kind? If it is of the first kind, how would we show that? Well, there are lots of rationals and irrationals as we approach from either side. Note that if we took an -ball around 0 then we could find a -ball around so that is within of 0, which would show that on the left- and right-hand side we have a limit of 0. So in this second example, with the modified Dirichlet example, all discontinuities are of the first kind. These are simple discontinuities. So we've changed here the nature of the discontinuities. Let's do another example.

-

Another discontinuous example: Suppose we have the function

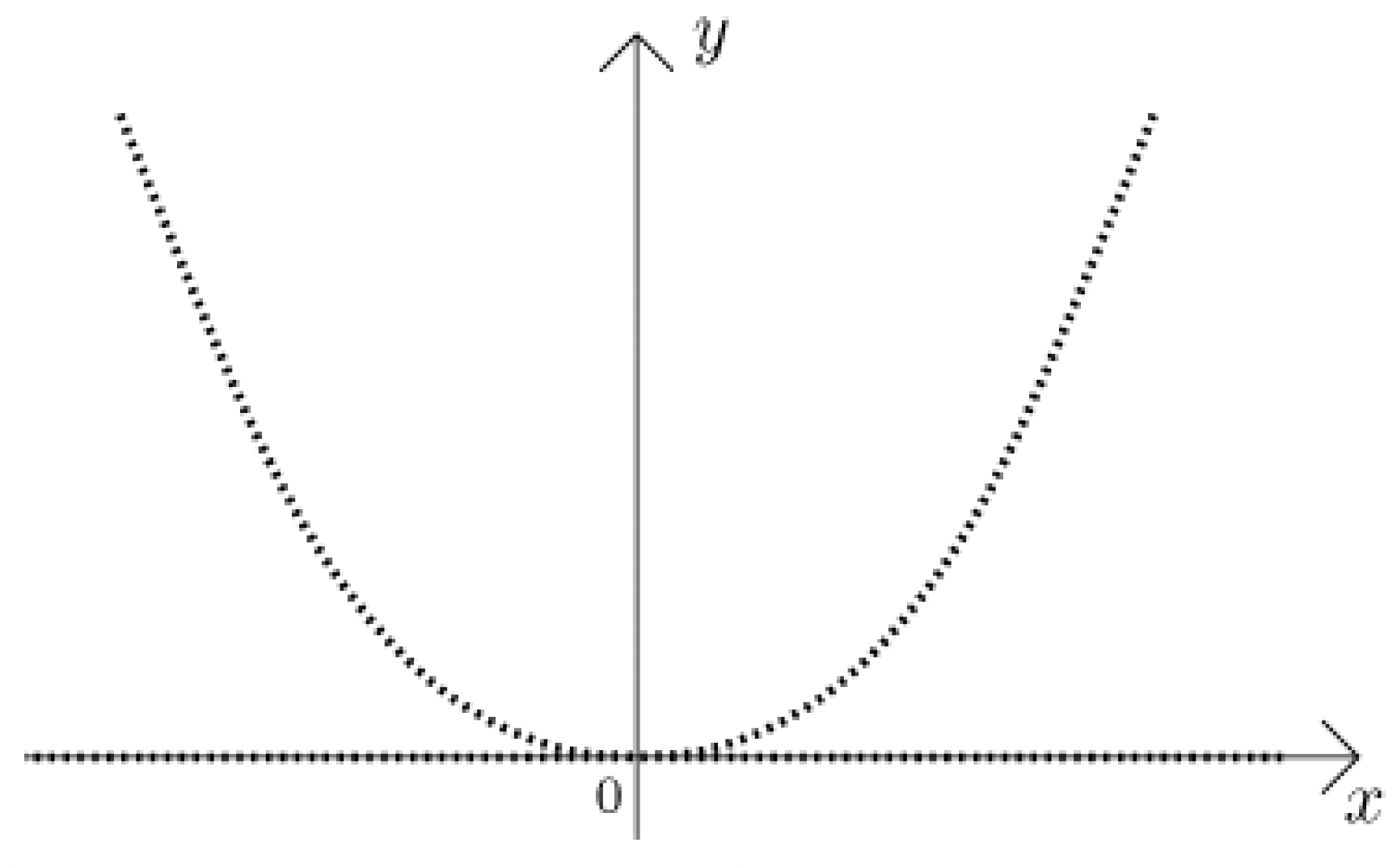

What kind of function is this? It would look like the following:

What kind of discontinuities do we have here? First of all, where are the discontinuities? Every point except possibly . Is it continuous or discontinuous here? To show that is continuous at , let's show that, in fact, around and its image (which is 0), that for -ball there is a around which that if you're within that then you're within the . True? Yes. So is continuous at 0. What is the nature of the discontinuities? Are they all of the second kind? Yeah, let's see why. How could we verify that? Suppose we considered a point and its image:

We want to know whether or not this has a limit coming from the left or from the right. Well, the only possibility is that the limit coming from the right would be 0. You could test all the other points, but it's pretty clear it's not going to be anything else. Regardless, there's not going to be a -ball that will leave you within of the proposed limit (or even the proposed limit of 0 either). So is continuous at 0 and discontinuous of the second kind elsewhere. Good. So now we have some idea what simple discontinuities are and what crazy discontinuities are.

Monotonicity and discontinuities

What happens when we try to restrict the kinds of discontinuities that can occur? What is good about monotonic functions and how do they play a role in all of this?

-

Motivation: We can restrict the kinds of discontinuities that can occur, and this leads to the topic of monotonic functions.

-

Definitions: A monotonic function basically means either monotonically increasing or monotonically decreasing. We say is monotonically increasing if implies that . We say is monotonically decreasing if implies that . What can we say about monotonic functions?

-

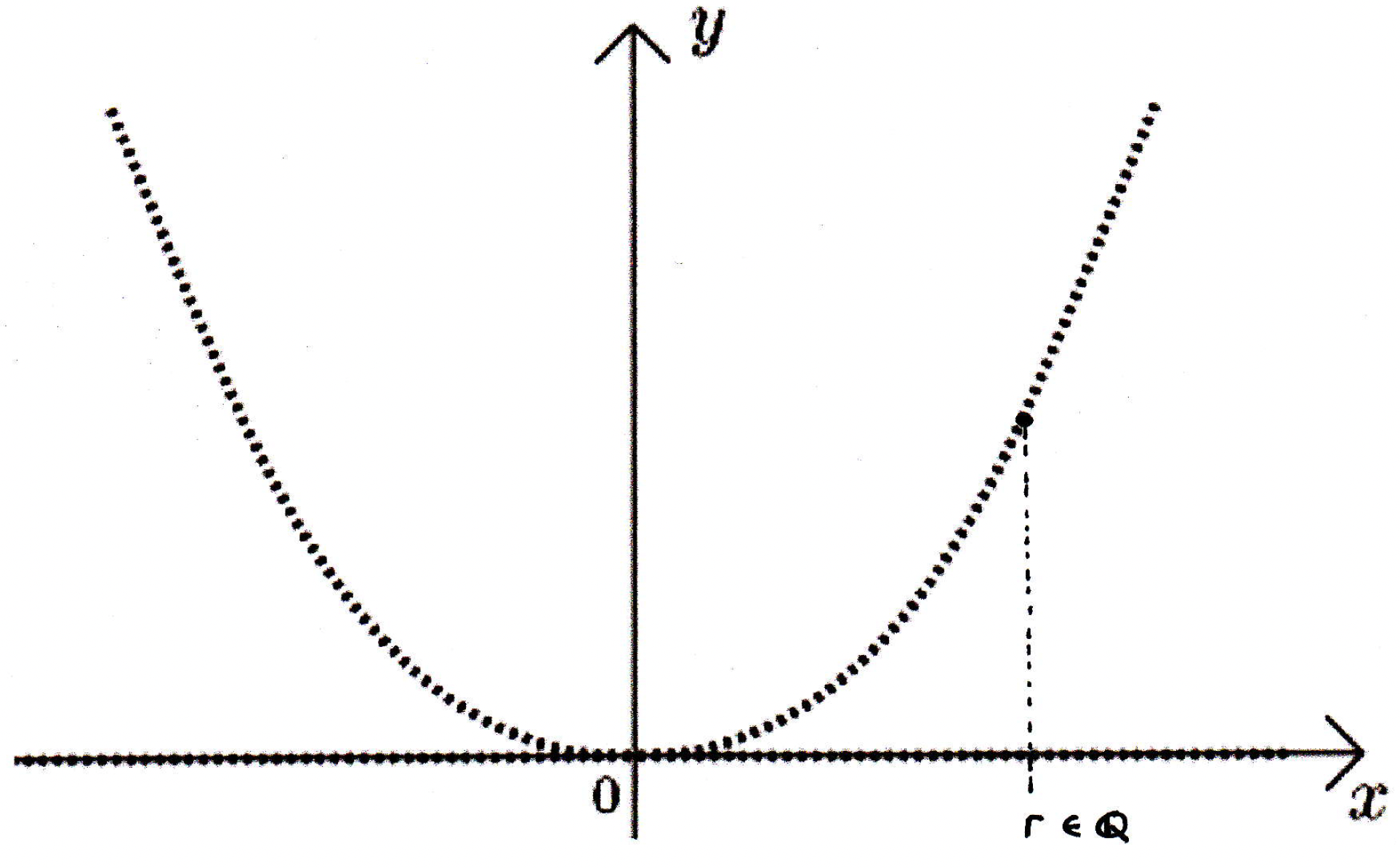

Motivating example: Consider the following function:

Clearly this function is monotonic. Are we prepared to make any kinds of conjecture about the kinds of discontinuities a monotonic function could have? Only simple? Is there any way a monotonic function could have a discontinuity of the second kind? It turns out no.

-

Theorem concerning discontinuities and monotonic functions: If is monotonically increasing on , then and exist for all .

Let's see if we believe that. Why is it true? What's the idea here? Why do the left- and right-hand limits have to exist? We claim something more is true. In fact, whatever the value of is, if we look at all the values achieves to the left of and take their supremum, then should still be at least as much as that, and if we look at all the function values on the right of and look at their infimum, then should be less than or equal to that infimum. So we have

How do we know the supremum and infimum actually exist? These values are bounded by . So we are okay in claiming they exist because is bounded above and below. Similarly, is bounded above and below so exists as well. Does that help us? Does it give us some idea as to what is happening? Let's see.

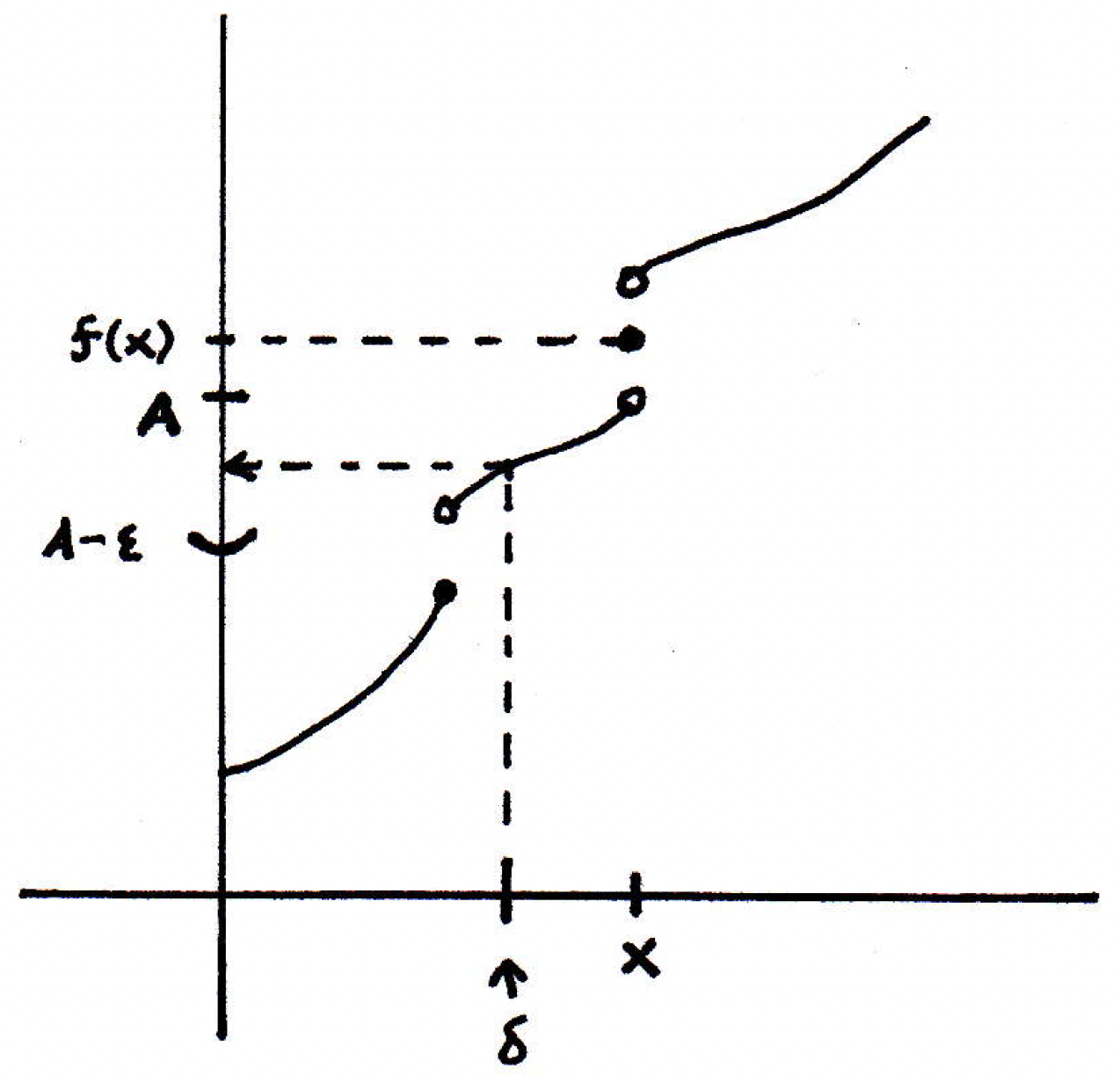

From above, let's let . Then our claim is that . Let's draw another picture to represent what is happening:

So all we have to do to verify that is to show that the limit of all the values coming from the left is, in fact, the number . Let's take an -ball around (it doesn't matter whether or not it contains the other side):

Given , consider . Certainly there are some values of that are bigger then since is a supremum. Thus, there exists such that by the definition of supremum (since is a supremum). That means there is at least one point we can find to the left of (i.e., ) whose value lives in the -ball (i.e., ). Can we show that all the points within some neighborhood on the left of must live in the -ball? Yes, because the function is monotonic. So, in fact, the pictured above works. So any must satisfy . So , as desired. That's the basic idea. The argument is similar for the other side.

-

Corollary to above theorem: The corollary to the above theorem is that monotonic functions have no discontinuities of the second kind. This corollary has a very interesting consequence, and this is the following theorem.

-

Consequence of corollary (theorem): If is monotonic on , then the set of points where is not continuous is countable.

If we look at a function that is monotone, like the one above, then if it has discontinuities, then they are basically jump discontinuities. So why must there only be countably many jumps? Well, for every point, the function has a left- and right-hand limit that exists. Basically, every discontinuity has a gap, and those gaps are intervals. Those intervals are all disjoint since our function is monotonic. So you could pick a rational in every interval. Then there cannot be uncountably many disjoint intervals in . So the proof idea is basically that for all where is discontinuous to pick such that . So the thing to notice is that if you have two discontinuities, then the you pick will actually be different. So if , then because is monotone. So what you would have is a one-to-one correspondence between the set of discontinuities and a subset of the rationals. What does this mean? Well, one of the consequences of this is that if we did have a function that was not continuous at the irrationals but continuous at the rationals, then the function could not be monotonic.