12 - Relationship between compact sets and closed sets

Where we left off last time

-

Compactness: Last time we saw that compact sets are, in some sense, small sets. They're the next best thing to being finite. In particular, finite sets are compact. We also saw that compact sets are, in fact, bounded sets. We proved that last time. And today we will show that compact sets are, in fact, closed sets as well. But we'll also see some other relationships between closed sets and compact sets.

-

Compact (definition): A set in a metric space is compact if every open cover of has a finite subcover in . We'll start off by showing something we alluded to last time, namely that it really doesn't matter what space you're embedded in. That is, compactness is actually an intrinsic property of a set, and it is actually does not depend on the metric space you're embedded in.

-

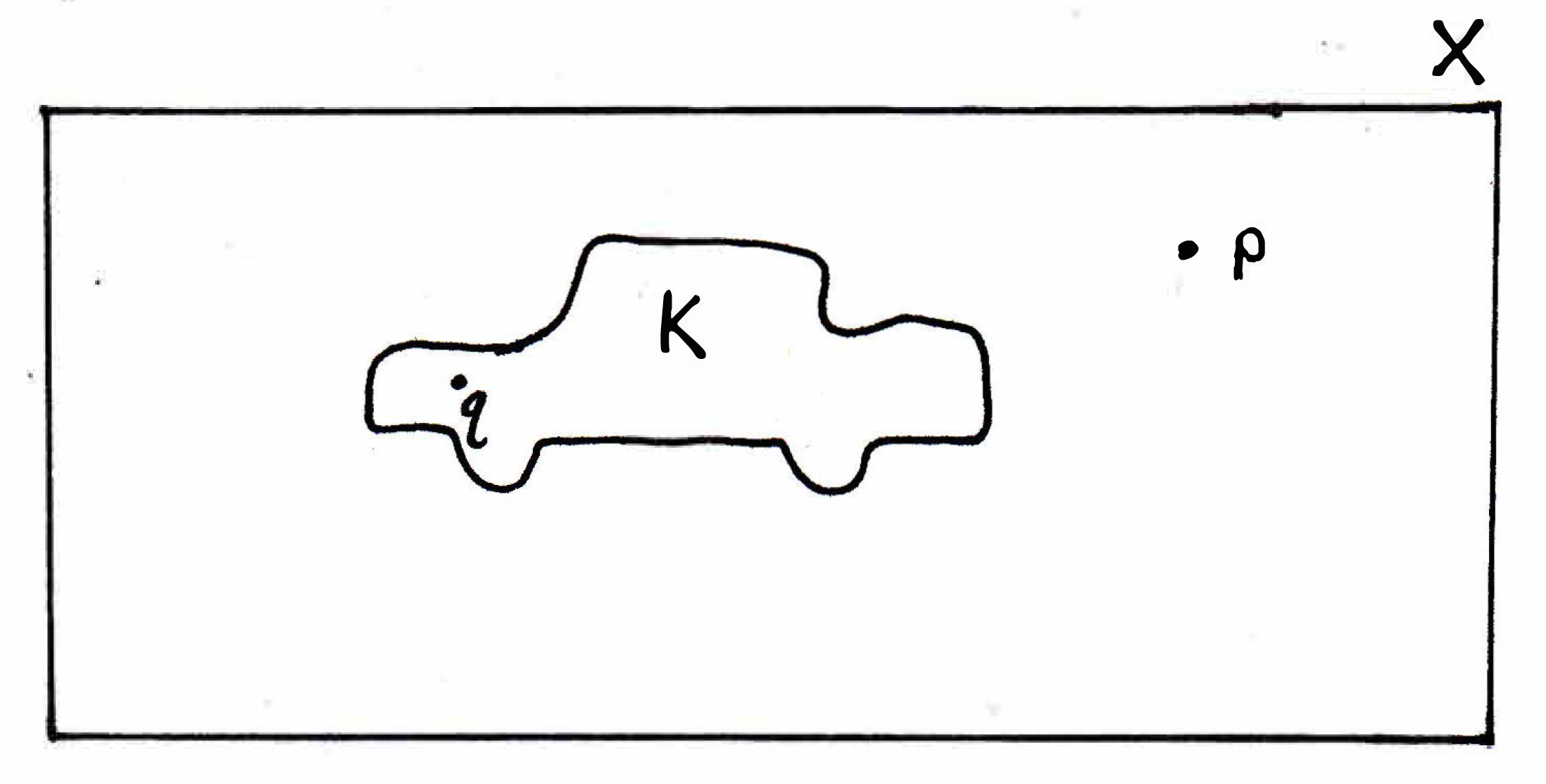

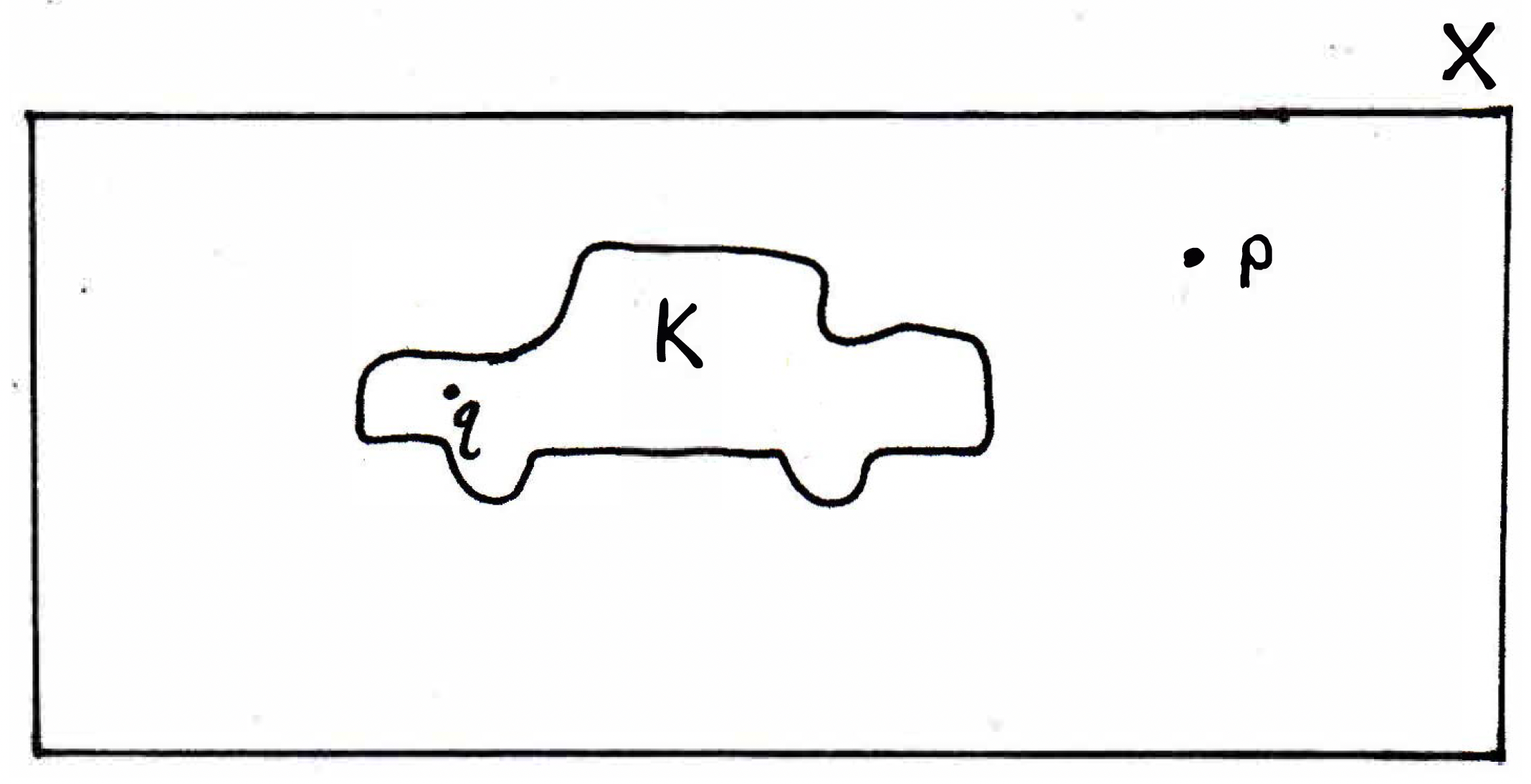

Recollection of openness in a metric space: Recall the characterization we had for what it means for a set to be open in a metric space. So consider a metric space and maybe some smaller metric space :

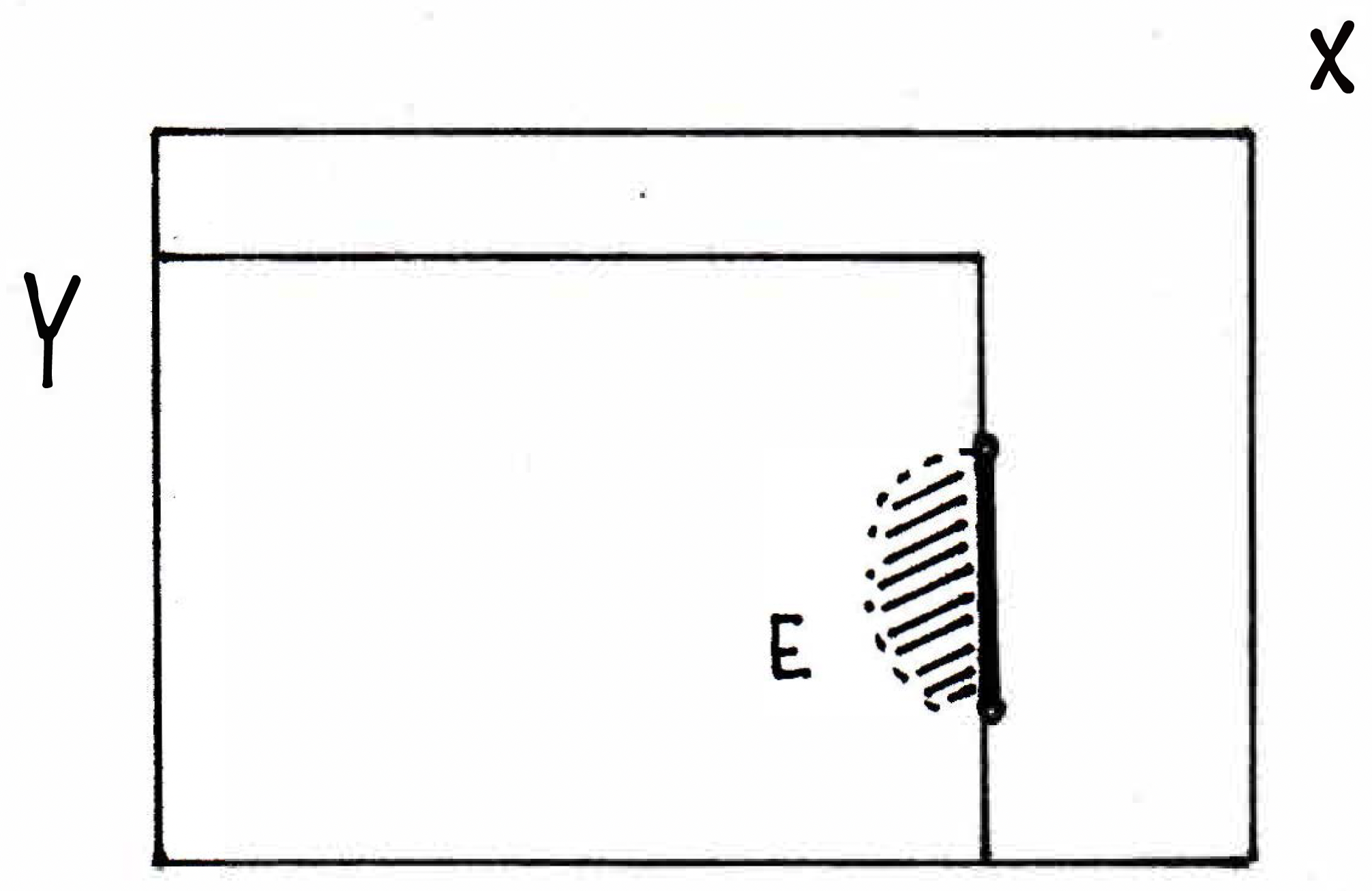

We might ask, "What does it mean to be open in ?" Well, what does it mean for a set to be open? It means every point of the set is an interior point. Or another way of saying it is that every point can be perturbed a little bit and stay inside the set. That's what it means to say the set is open. But last time we made a distinction about what it means for a set to be open in as opposed to . You could imagine, for instance, a set such as

which does not contain its boundary on the left-hand side (indicated by the dashes) but does contain its boundary on the right-hand side (indicated by the dark bold line), where we also notice the open endpoints of the bold boundary. Is the set open in ? No, it's not open in because you could be right on the bold boundary and perturb a little bit and you would leave the set . The point would not be interior. There is not an open ball, neighborhood around it that's still within . (In the picture this is communicated because any point to the right of the boundary would no longer be in , thus causing to not be open in . But is open in ? Yes, because in , if we perturb it a little bit, would you still remain in if you only moved within ? Yes. But what about the endpoints on the boundary? (In the picture, these endpoints are open even though you have to zoom in slightly to see it.) If the endpoints of the bolded boundary were actually in the set , then would not be open in either because you could march to the northwest direction of the top point and leave the set . That point would not be interior to if it were included. So the set in this example here is an example of a set that is open in but not open in . But there is a relationship as we saw last time.

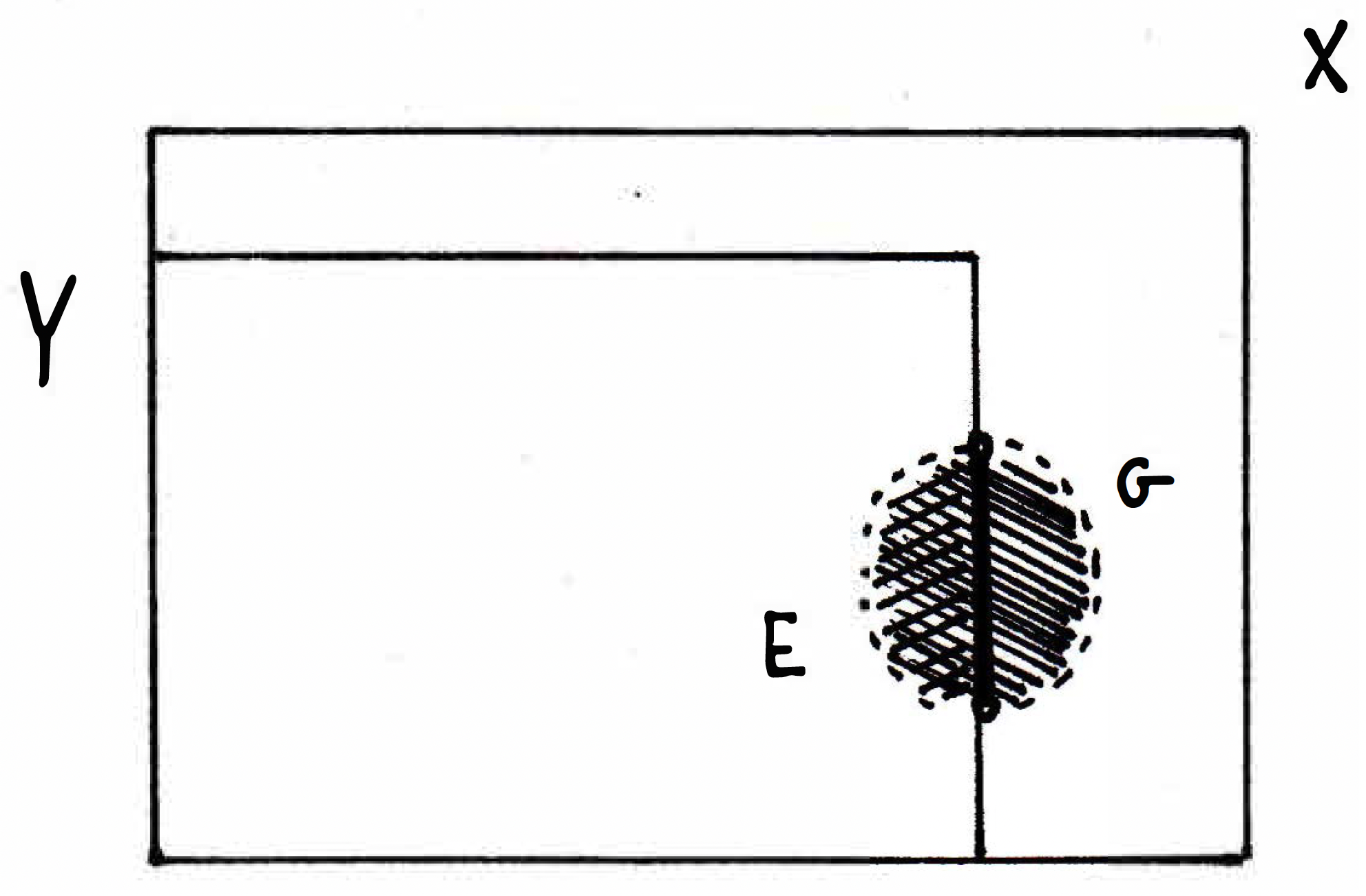

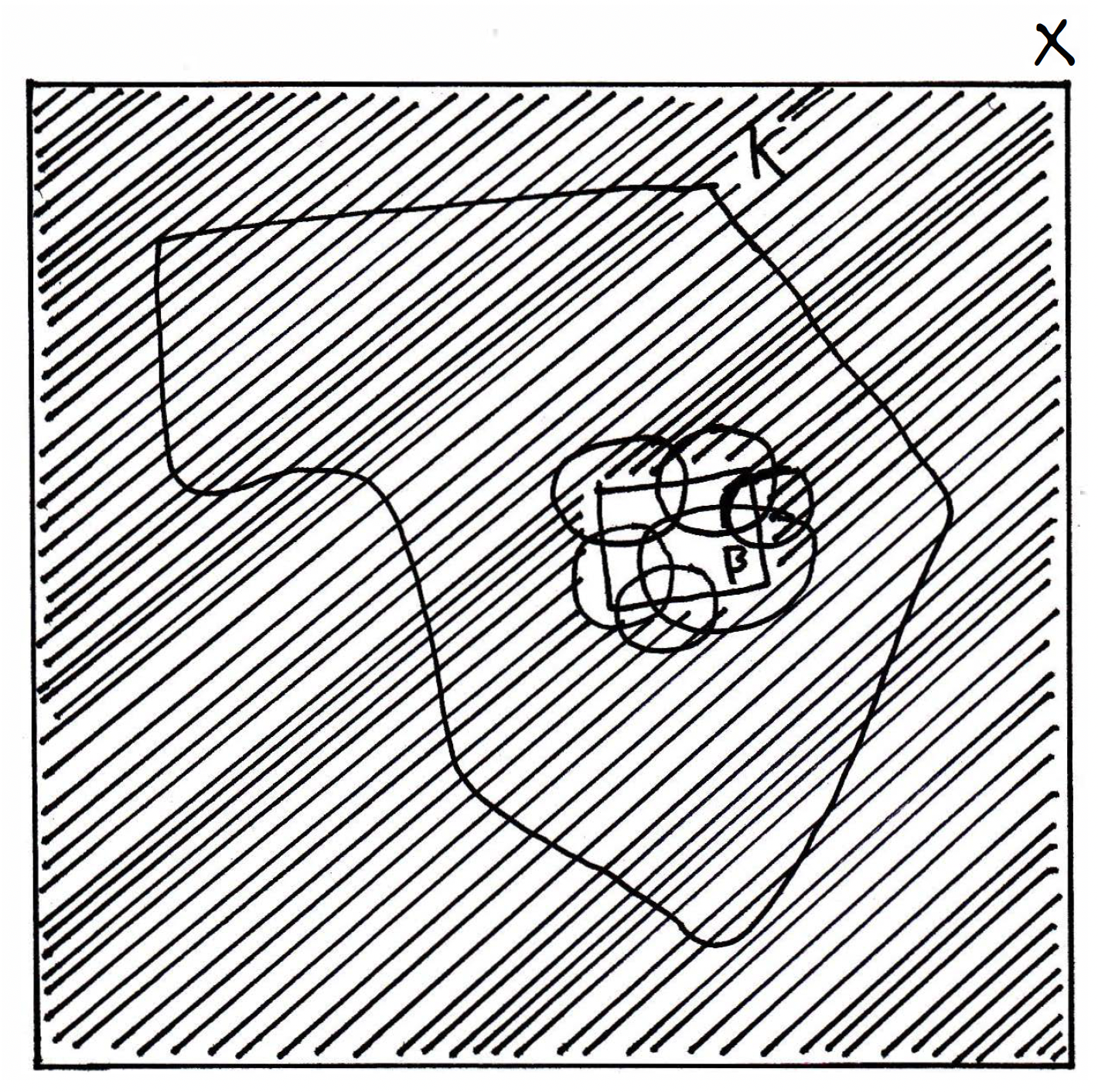

The thing we proved last time was that even if the pictured set is not open but is open in , then there exists a corresponding set that is open in such that is the intersection of this set with . That is, . That was the theorem from last time, and we can visualize the result in this example with the picture

where is everything in the disc (indicated by diagonal lines going from top left to bottom right). So the theorem we proved last time was that if it is the case that , then is open in if and only if for some open in . So this is the correspondence between being open in a metric space that is a subset of a bigger metric space. The book states this theorem more precisely as follows.

Theorem. Suppose . A subset of is open relative to if and only if for some open subset of .

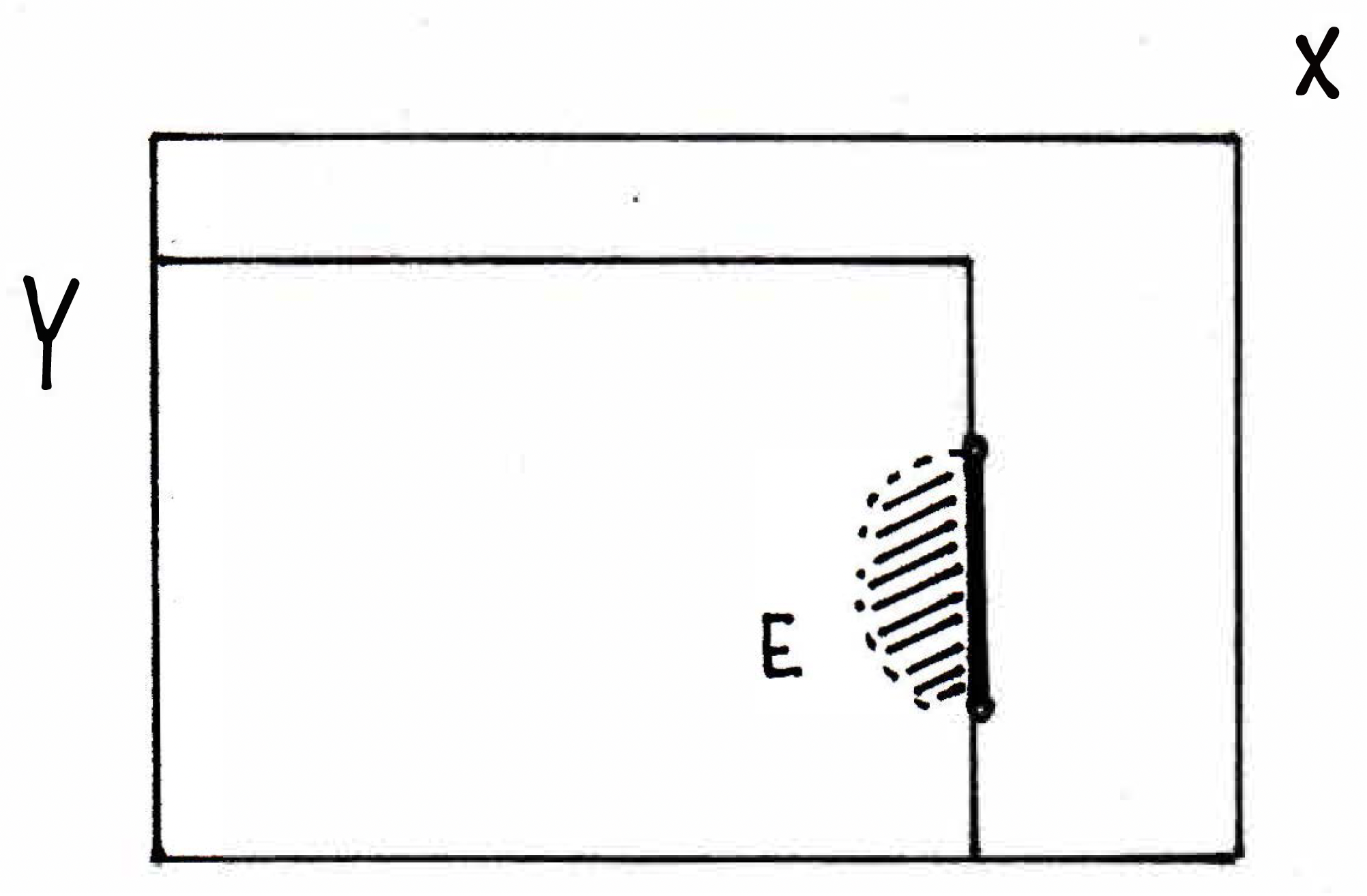

What this theorem essentially means is that any open set in , namely in our example, corresponds to some open set in , namely in our example. The set could correspond to several open sets in for which , but it must correspond to at least one such open set. Similarly, any open set in must correspond to an open set in just by taking the restriction to . This insight is going to be the ingredient in showing that compactness is really not dependent on the space you're in. For example, consider again the following picture:

If we want to talk about the set being compact, then whether or not I choose to talk about compactness in or compactness in , it really does not matter. It's the same. Let's see why that's true. What we're really going to have here is some set . So you might imagine the set depicted below by the very bold line.

And we might want to know whether or not the set is considered to be compact. And so now the question is what does it mean to be compact? I need to show that every open cover has a finite subcover, and if I want to talk about compactness in then there had better be an open cover for in . So then we would use open sets like pictured above to cover , and I want to know is it true that if is compact in , then is there some relationship between being compact in , which would involve covering by sets like pictured above. The theorem we are about to prove says that the notions are, in fact, equivalent.

Compactness results

What are some key results and proofs concerning compactness?

-

Compactness independent of metric space: We shall prove that, given , that is compact in if and only if is compact in . Let's go with the forward direction first in our proof.

-

Forward direction: What are we assuming here? We are assuming that is compact in . That means given any cover of by some open set in I can find a finite subcover by similar sets . That's what we're allowed to use if we need it. But how should we actually start this proof? What do we want to show is compact? We want to show is compact in . So we should start with an open cover of by sets of the form (as in our picture above) in . Our job, then, will be to show that does, in fact, have a finite subcover in . Let's get started.

Consider an open cover of in , where the sets here are like in the previous picture, and here just means an arbitrary open collection. We're not bothering to write the index set, but it could possibly be an uncountable index set. So we have an open cover of by a bunch of sets like , namely . We want to show that has a finite subcover. How can we do this? And all we know is that if we have sets like then we can find a finite subcover by such sets. Let . Then are an open cover for in . Is it clear that actually cover ? Yes, because . By compactness of in , there exists a finite subcover . So we're just turning our intuition into a proof. So what's the finite subcover you're expecting to use now that's similar to in the previous picture? We should go back to the original sets. Which ones? The ones that are indexed by . Then is a finite subcover (of the original cover) of in , as desired.

-

Backward direction: Now we will assume compactness in and show compactness in . So we'll start with what kinds of sets? What kind of cover? We should start with an open cover of in for this direction of the proof. So consider an open cover of in . So now we want to show that there is a finite subcover. The argument here is very similar. I start with a bunch of sets like covering in , and I want to find a finite subcover. What should I do? Well, by the theorem

Theorem. Suppose . A subset of is open relative to if and only if for some open subset of .

we are saying that every element of the cover corresponds to a bigger that's open in the bigger space . That's an open cover. It has a finite subcover. And now restrict to get sets like , and that's a finite subcover of the original cover.

More precisely, by the theorem relisted above, there exists open such that . Then cover in so there exists a finite subcover . Then are a finite subcover of for in . This is good enough for a sketch of the argument, but there are a few things to check. If someone really pressed you, then you might still want to explain why still covers in .

So what's the moral of the story here? The moral of the story is compactness is an intrinsic property of a set. It doesn't depend on what metric space you're embedded in. Just has to be one that contains that set.

-

-

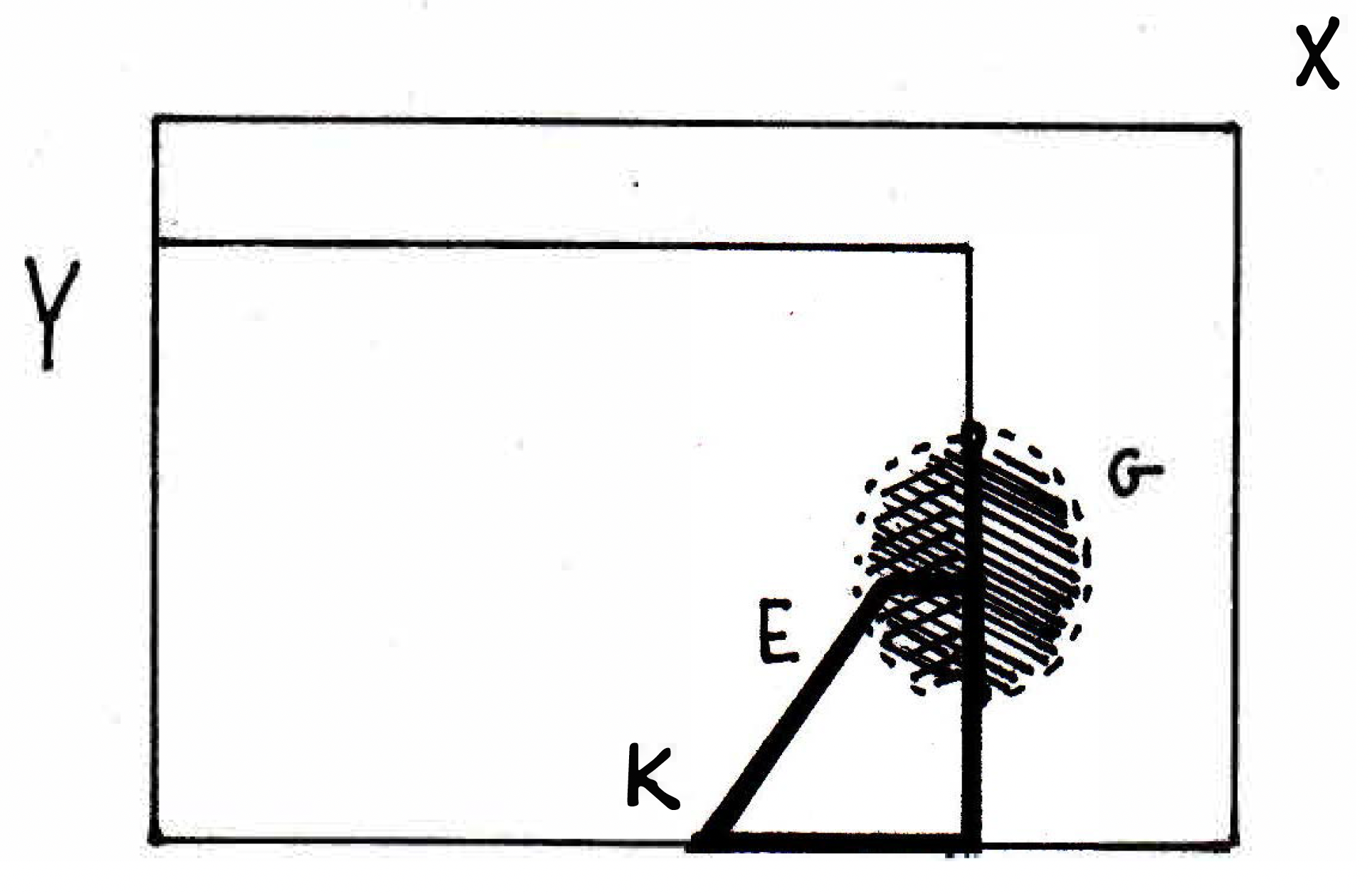

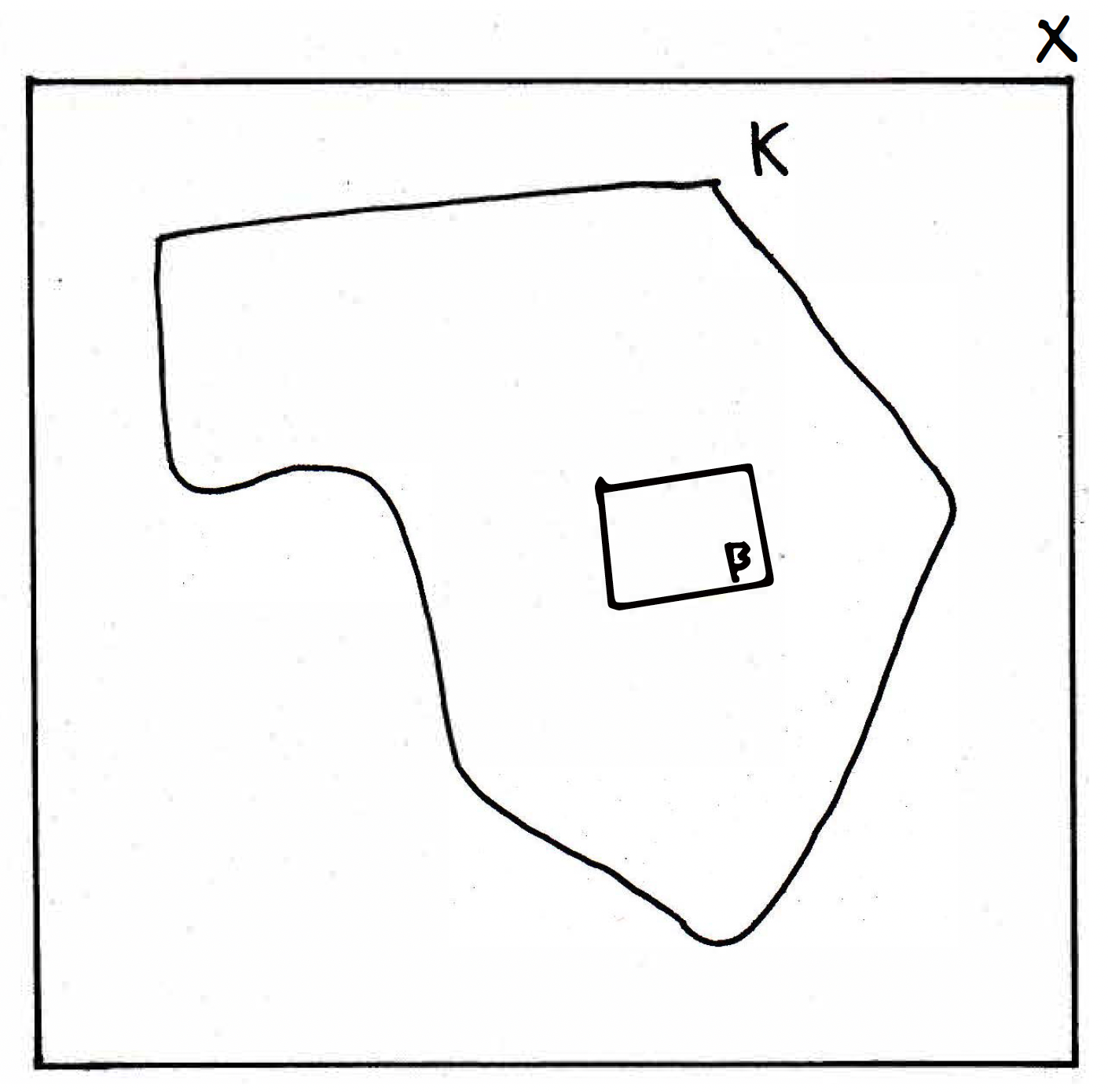

Motivation for proof that compact sets are closed: Consider a metric space and some set embedded in , where is a compact set (it's a compact car!) and represents an arbitrary point in while represents an arbitrary point in that is not in (so just an arbitrary point outside of ), and we want to show that is closed.

How are we going to show that is closed? What's one way we could try to do this? When is a set closed? A set is closed when it contains all its limit points or, alternately, a set is closed if its complement is open. Which of those characterizations might be most helpful here? Complements are open! Why might that be more helpful in this context where we are dealing with the definition of a concept like compactness? Because it's talking about open covers! So let's try that strategy.

We are going to take any point outside of the set and show that there is a ball around it, a neighborhood around it, that misses the car. That's our goal. Why is that our goal? Well, we want to show that is an open set. What is an open set? (With what follows we will use instead of to more clearly illustrate what we are trying to show in this proof.) A set is an open set if every point of is an interior point. What's an interior point? A point is an interior point of if there is a neighborhood of such that . It should be clear now that if we can find a neighborhood of in the picture such that this neighborhood misses all of then we will be done because is an arbitrary point of ; that is, if we can show that is an open set by showing that each is an interior point, then we will have shown that is closed, the desired conclusion.

Let's return to our picture:

How can I produce a neighborhood or open set (recall that all neighborhoods are open sets) around such that it misses the car? To "miss the car" we kind of need to know something about the points that make up . Let denote an arbitrary point of . Then the notion of constructing a neighborhood around such that it misses the car will necessarily involve some idea concerning the distance from the arbitrary point in to the point in . Now, when thinking about constructing such a neighborhood around , we necessarily think of the distance or radius of such a neighborhood (after all, such a distance is the defining characteristic of a neighborhood), but instead of thinking about distances from you might look at balls or neighborhoods around .

From the picture, it seems to be an agreeable notion that for any particular point in we have a predetermined ball such that this ball completely misses a ball for some point in . Yes, so let's give it a name. Consider the set around that misses 's ball. Denote this set by . And also consider the set around that misses 's ball. Denote this set by .

Now, different 's will have different balls, and their radii may change based on their proximity to . The idea is that for every point there are partner sets that separate that point from . Call them and . What should we do now? Use the set of 's as a cover for ! Yes, this will be a cover. So what? Since is compact, there is a finite subcover. If we have a finite subcover, then what this means here is that we have a finite number of these balls for and also a finite number of these balls for (i.e., partners). You could take the one of minimum distance. Why does that minimum have to be bigger than zero? Why does it have to exist? There are now finitely many distances we are talking about! Why does it have to be bigger than zero? Because it was bigger than zero to begin with.

The punchline is that now we've used finiteness. We basically have finiteness where we didn't have it before. That's what we mean when we say that compact sets are the next best thing to being finite. We are actually appealing to finiteness here. Okay, so let's give the proof now that motivation has been properly given.

-

Compact sets are closed: Clearly we are talking about compact sets being closed in a metric space, but why is this true? Let be compact, and consider . We want to show that has a neighborhood that does not intersect . That's the same as showing that is not a limit point of which would also show that any point that's not in it is not a limit point so contains all its limit points or it's the same as showing that the complement of is open. Either way, we are done if we can do this. (So is interior to \ldots if this is true for all then is open.)

For any , let , and let , where . Note that are an open cover of . By compactness of , there exists a finite subcover . What should we do with the sets? We should look at their partner sets. Then let , where is the intersection of finitely many things. Since is the intersection finitely many open sets, then itself is open, and is a ball of radius of . So what do we claim about ? We have a bunch of partner sets, and the smallest one is the one we're interested in. So the claim is for each . Why? Because , and . We are done because is the desired neighborhood.

-

Recap of proof of compact sets being closed: The amazing idea used in the proof is that we can separate from each point; there are infinitely many points, but that's where compactness comes in. It's a beautiful idea. So we now know that if a set is compact then it must be closed.

-

A consequence of compact sets being closed: An easy consequence of the observation that compact sets are closed is that the open interval is not compact. We've already seen an open cover that doesn't have a finite subcover (i.e., concentric things getting bigger and bigger). But now we can see from this theorem that it's also clearly not compact. If it's going to be compact, then it has to be closed. What else can we say about the relationship between compact sets and closed sets? Compact sets are closed, but are closed sets necessarily compact? No? Give me an example. How about the entire real line in the real line? It's not compact because it's not bounded. So notice that (in ) is not compact because it is not bounded even though it is closed. So closed sets are not necessarily compact. What about ? It's closed, but it's not compact because it's not bounded either. Are closed and bounded sets compact? Not necessarily in every metric space! But it is true in ! This result is known as the Heine-Borel theorem. Interesting aside question: Given some arbitrary set , is it possible to make a compact set by finding an appropriate metric space for which we are not dealing with a pseudometric? Okay, so closed sets are not necessarily compact, but here's one thing we can say (and this leads up to the Heine-Borel theorem): A closed subset of a compact set is compact.

The Heine-Borel theorem

How might we set ourselves up well for the proof of the Heine-Borel theorem?

-

Closed subsets of compact metric spaces: We showed compact sets are closed, but now we are addressing the question of whether or not closed sets, in particular cases, are compact because they're not necessarily compact in general (as was seen above), but one instance where we can say they are compact is if we take a closed subset of a compact set. Let's prove this: A closed subset of a compact set is compact.

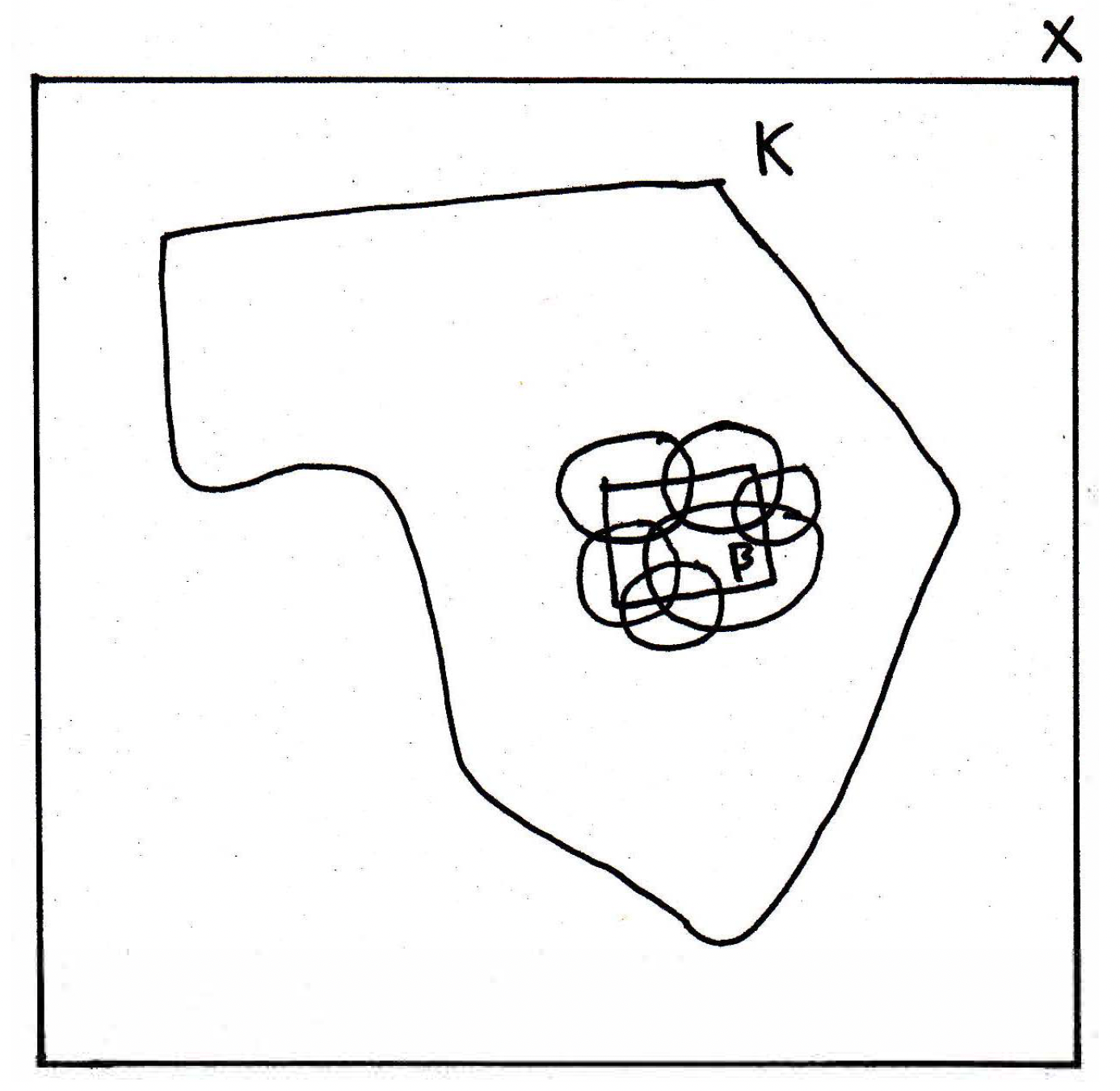

Consider some compact set with as a closed subset of such as the following:

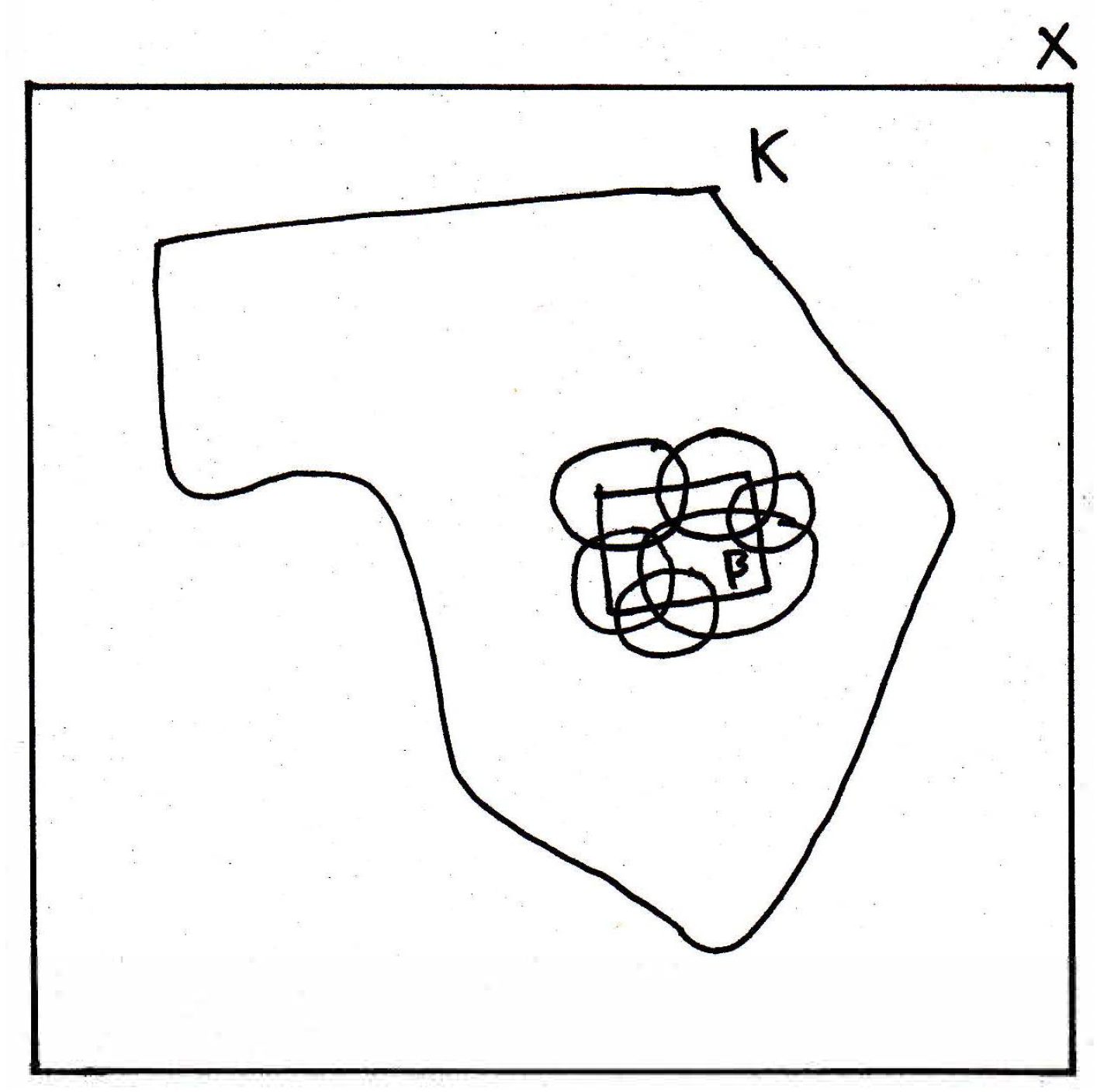

The claim is then that is compact. This is another fun argument with compactness. So, we want to show is compact. Which means we should start with an open cover of what? We should start with an open cover of ! The temptation is to start with an open cover of , but that is a mistake. We will need to use the fact that is compact at some point certainly, but our goal is to show that is compact from this. (And we know that has an open cover because is a subset of , and is already known to have an open cover\ldots but which one should we use? That's a question addressed below.) So let's start with an open cover of . Let be an open cover of . So here's an open cover of by sets here:

Of course, there could be many more sets involved in this open covering, but the above suffices. Now we want to find a finite subcover of using this collection . How can we do that? What do we know? We know is compact. So if we're going to use the fact that is compact, then I'm going to need to have an open cover of . Certainly, if we want to find an open cover of , then there must be some relationship with the sets . So let's use our sets which don't necessarily cover all of . So what should we do? Add more sets perhaps. Now, would you agree that if we add more sets, then it might be a bad thing to add infinitely many sets? Because then when you take the finite subcover you might not get any of the original sets . So can we see an open set or sets that cover(s) the things that we have missed? Here is a hint: is closed. How is this helpful? The sets cover , and we need something or some things to cover everything outside. I know that is closed. Therefore, must be open, and what does this do? It covers everything outside of ! So is everything outside of , possibly more than , but that's okay, we don't have a problem with that:

Everything enclosed with horizontal dashes represents in the figure above. (Note how the dashes go through the open sets that cover but do not cut across itself.) Since is closed, we know is open, and the question is whether or not we have an open cover of now. Yes. And is compact. Therefore, has an open cover.

Right now we have that is an open cover of and that is open (because is closed). So is an open cover of . Therefore, by compactness, there exists a finite subcover of , namely the collection , where we throw in as a safety precaution (throwing into the collection does not change the finiteness requirement of the subcover). Recall the open covering of we had at the beginning:

If this open covering covered all of as well, then might not be needed in our collection , but otherwise it's together with some things of . So right now we have that is a finite subcover of the cover , where may or may not be needed in , but its inclusion or exclusion does not effect the finiteness condition so we include it anyway. Is the collection a finite subcover of the original open cover of ? If so, then we are done. If not, then we will need to do some more work. Well, may not be a finite subcover of because it may have in it. So what can we do? Well, is not covering anyway so it's not necessary for . It might be necessary for , but it's not necessary for . We are now in a place to wrap things up.

Let be an open cover of . Note that is open since is closed. Thus, is an open cover of . By compactness, there exists a a finite subcover of . Note that ; thus, covers and is a finite subcover of the original cover of .

-

Recap of proof for compactness of closed subsets of compact sets: What have we shown? We've shown that if you consider a "small set" (i.e., a compact set) and take a subset of this small set, then this subset is also a "small set" (i.e., the subset of a compact set is also compact). What else can we say about compact sets?

-

Corollary of proof: If you have a closed set and a compact set , not necessarily related, in a metric space , then the intersection is compact. Why is this a simple corollary? Well, if is compact, then is closed. Hence, is closed because and are both closed. But is then a closed subset of a compact set and is therefore compact.

-

Lemma for Heine-Borel Theorem (nested interval property): We want to show, in the Heine-Borel theorem, that closed and bounded subsets of the real line are compact. To do that, we first need to show that closed intervals are compact, which we have not done yet. So we need to do that. And to do that, we need the nested interval theorem.

-

Nested interval theorem: The intersection of nested closed intervals in are not empty. (The same fact will be true in is we replace "intervals" with -cells, which may be thought of as closed boxes in many senses.) We can imagine we have , where by nested we mean

and . The idea is that there exists a point in all (i.e., the intersection) of the closed intervals. How do we know there exists such a point? What's a possibly good candidate to consider? What if we start to consider , and so on? How about a supremum for the ? Why does such a supremum have to exist? Because we have a bunch of real numbers! We're definitely upper bounded by .

Let , which exists because they are bounded by . So we have a candidate and it exists. Why must be in all of these intervals? Is it clear that is at least bigger than all the ? Yes! It's the supremum. So, clearly we have for all because is the supremum. Why is less than all the 's? We have to be a little more careful here. Why does have to be less than, say, ? We claim for all because is an upper bound for all by the equation above. So what are we saying? You give me any , I claim it is bigger than every , and the reason is you give me any like it's bigger than because, for example, is bigger than . If you want to show, for instance, that is bigger than , then all you have to do is appeal to the equation above and note that . And we can do that for any , and that is enough to conclude the proof. This is such an important concept that it is even powerful enough to prove that is uncountable, a task you may recall took quite a bit of effort to do previously.

-

Uncountability of the reals using the nested interval theorem: Suppose is countable; that is, list as a sequence: . Se we can list out the on the real line in no particular order. They could be hopping around. Well, you cannot stop me from choosing an interval that misses . Then we will choose another interval, , such that is in (i.e., ) but misses both and . (Clearly will miss since and already missed .) We could continue this process indefinitely, where we would have a nested sequence of intervals such that each interval missed the real number . However, by the nested interval theorem, the intersection of all is nonempty; thus, there exists a point in the intersection of all the that is not on the original list for , a clear contradiction to how we have constructed the intervals . More concisely, there exists such that . This concludes the proof.

Where's the hard work done in the proof above? In the previous proof for the uncountability of , we expended a fair amount of effort, but the above looks fairly painless. So where was the hard work done? It's in all the machinery we built up for suprema and other such facts. Next time we will prove the Heine-Borel theorem characterizing compact sets in Euclidean space.